Surgery for distal rectal cancer (DRC) can be performed with or without sphincter preservation. The aim of the present study was to analyze the outcomes of two surgical techniques in the treatment of DRC patients: low anterior resection (LAR) and abdominoperineal resection (APR).

MethodsPatients with advanced DRC that underwent surgical treatment between 2002 and 2012 were evaluated. We compared the outcomes of the type of surgery (APR vs LAR) and analyzed the associations of survival and recurrence with the following factors: age, sex, tumor location, lymph nodes obtained, lymph node involvement, and rectal wall involvement. Patients with distant metastases were excluded.

ResultsA total of 148 patients were included, 78 of whom were females (52.7%). The mean patient age was 61.2 years. Neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy was performed in 86.5% of the patients. APR was performed on 86 (58.1%) patients, and LAR on 62 (41.9%) patients. No differences were observed between the two groups regarding clinical and oncologic characteristics. Eighty-seven (62%) patients had pT3-4 disease, and 41 patients (27.7%) had lymph node involvement. In the multivariate analysis, only poorly differentiated tumors (P=.026) and APR (P=.009) correlated with higher recurrence rates. Mean follow-up time was 32 (16-59.9) months. Overall 5-year survival was 58.1%. The 5-year survival rate was worse in patients that underwent APR (46.5%) than in the patients that underwent LAR (74.2%) (P=.009).

ConclusionsPatients with locally advanced DRC that underwent APR presented with a lower survival rate and a higher local recurrence rate than patients that underwent LAR. In addition, advanced T/stage, lymph node involvement, and poor tumor differentiation were associated with recurrence and a lower survival rate, regardless of the procedure.

La cirugía de cáncer de recto distal (CRD) puede ser llevada a cabo con o sin la preservación de esfínter. El objetivo del presente estudio fue analizar los desenlaces de dos técnicas quirúrgicas en el tratamiento de pacientes con CRD: resección anterior baja (RAB) y resección abdominoperineal (RAP).

MétodosSe evaluó a pacientes con CRD avanzado que se sometieron a tratamiento quirúrgico entre el 2002 y 2012. Comparamos los desenlaces por tipo de cirugía (RAB vs RAP) y analizamos las asociaciones de sobrevida y recurrencia con los siguientes factores: edad, sexo, localización de tumor, ganglios linfáticos afectados y obtenidos, y afectación de la pared rectal. Se excluyó a pacientes con metástasis distantes.

ResultadosSe incluyó a un total de 148 pacientes, de los cuales 78 eran mujeres (52.7%). El promedio de edad de los pacientes fue de 62.1. Se realizó radioquimioterapia neoadyuvante en 86.5% de los pacientes. Ochenta y seis pacientes (58.1%) se sometieron a RAP y 62 (41.9%) a RAB. No se observaron diferencias entre los dos grupos respecto a las características clínicas y oncológicas. La enfermedad de 87 pacientes (62%) era pT3-4 y en 41 (27.7%) pacientes existía afectación ganglionar. En el análisis multivariado, solo los tumores con diferenciación pobre (p=0.026) y la RAP (p=0.009) estuvieron correlacionados con una tasa más alta de recurrencia. El tiempo promedio de seguimiento fue de 32 meses (16-59.9). La sobrevida de 5 años general fue de 58.1%. La tasa de sobrevida de 5 años fue peor en pacientes que se sometieron a RAP (46.5%) que en pacientes que se sometieron a RAB (74.2%) (p=0.009).

ConclusionesLos pacientes con CRD localmente avanzado que se sometieron a RAP presentaron una menor tasa de sobrevida y una tasa más alta de recurrencia local que los pacientes que se sometieron a RAB. Además, la etapa T/avanzada, la afectación ganglionar y la diferenciación tumoral pobre estuvieron asociados con mayor recurrencia y tasa más baja de sobrevida, independientemente del procedimiento quirúrgico.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the most common malignancy of the digestive tract and its incidence has increased in recent years, particularly in areas considered to be at low risk, such as developing countries.1 In 2016, approximately 34,280 new cases of CRC were reported in Brazil, with 16,660 cases in men and 17,620 cases in women.2 Rectal cancer accounts for approximately 30% of the patients with CRC.3

Evidence from previous studies has shown that up to 70% of patients with non-metastatic rectal cancer present as T3 or node-positive.1 The current management of advanced rectal cancer has moved toward a tailored approach based on preoperative staging, chemoradiation therapy, and subsequent restaging. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (NCRT) has improved local control and long-term results and has also facilitated sphincter preservation procedures.4–6 However, sphincter preservation procedures with total mesorectal excision (TME) are sometimes impossible to perform, even with long-course NCRT.7 The choice of a low anterior resection (LAR) with colorectal stapled anastomosis, ultralow coloanal anastomosis, or abdominoperineal resection (APR) depends on tumor height, the extent of its local invasion, and the surgeon’s skills. Decision-making regarding those procedures takes place during multimodal treatment, or even at the time of the surgery.8 Although said surgical procedures are not directly comparable, some studies have shown that patients treated by APR have a worse prognosis than those treated by LAR.8,9 However, other studies have described no differences in local recurrence rates, when the two procedures have been compared.7,10 On the other hand, in patients with low rectal cancers treated with LAR, some concern exists regarding a higher local recurrence rate due to incomplete resection of microscopic disease at radial and distal margins.

So far, there is no evidence that APR, itself, has worse oncologic outcomes than LAR. Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to compare the oncologic outcomes of LAR and APR, in the treatment of distal rectal cancer patients over a 10-year period. In addition, the risk factors for recurrence and overall survival were analyzed.

MethodsData on consecutive patients with distal rectal cancer that underwent curative surgical treatment at the Colon and Rectal Surgery Service of the Hospital das Clinicas de Facudade de Medicina de Universidade de Sao Paolo, within the time frame of 2002-2012, were retrieved from a prospective database of patients and retrospectively analyzed. Given the retrospective nature of the present paper, there was no need for patient authorization of the data.

Sphincter-preserving procedures, such as low or ultralow anterior dissection with colorectal or coloanal anastomoses (LAR), were compared with APR in patients with advanced distal rectal cancer located within 5cm of the anal verge.

The following factors were studied and analyzed: sex, age, neoadjuvant treatment, T stage, lymph node involvement, number of lymph nodes retrieved in the specimen, histologic type, and tumor differentiation. Those factors were evaluated in relation to cancer prognosis, such as local recurrence, overall survival, and disease-free survival.

Patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis or advanced distant metastasis (stage IV disease), synchronous colorectal cancer or other non-colorectal cancers, involved margins, rectal cancer in the setting of inflammatory bowel disease, familial adenomatous polyposis, or previous pelvic radiotherapy were excluded.

Patients with locally advanced rectal cancer underwent NCRT. Patients were staged and restaged before and after neoadjuvant treatment by the same colorectal surgeon and clinical oncologist through a digital rectal exam, proctoscopy, colonoscopy, pelvic MRI, and chest and abdominal CT scans.

Neoadjuvant treatment consisted of an intravenous bolus of 350mg/2 5-Fluoracil on the first and last 5 days of treatment, concomitant with radiotherapy. The total dose of pelvic radiation was 5,040Gy, which was given in 28 consecutive sessions of 180Gy. Restaging occurred between 8 and 12 weeks, and surgical treatment was performed at approximately 12-14 weeks.

All surgical specimens underwent histopathologic examination and were classified according to UICC TNM staging. Hematoxylin-eosin staining was used to identify lymph nodes (LNs). Neither bread loafing nor immunohistochemical node assessment was routinely used.

Surgical treatmentSurgical treatment included rectosigmoidectomy with TME and ligation of the inferior mesenteric vessel at its root. The surgical options were low or ultralow anterior resection with sphincter preservation or APR. The decision to perform sphincter preservation surgery was based on the evaluation of sphincter involvement during restaging tests and a proctologic examination to obtain tumor-free distal and circumferential oncologic margins. All surgical procedures were performed by board-certified colorectal cancer surgeons, following the principles of radical oncologic resection. Dissection of the mesocolon and TME with en bloc resection of contiguous organs were performed when adhesions or macroscopic tumor invasion were detected.

Statistical analysisThe present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of São Paulo School of Medicine (FMUSP) in São Paulo, Brazil.

Patient and tumor characteristics were described and compared between the two groups, using relative and absolute frequencies and the chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test, or the likelihood ratio test. The last two tests were applied when the sample was unsuitable for evaluation by the chi-square test. For the multivariate analysis, a logistic regression model including variables with a significance level below 0.2 in the bivariate analysis was utilized. Data were analyzed using the Windows SPSS 20.0 program.

To evaluate overall survival based on each variable analyzed, the mean survival time was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. The hazard ratio (HR) was estimated with a 95% confidence interval using bivariate Cox regression of proportional risks. Multivariate Cox regression was applied for variables that influenced overall survival. The final models included only variables with significance levels below 0.05.

Ethical considerationsThe present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and the Ethics Committee of our hospital. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study before enrollment. Patients were routinely treated according to standard international protocols.

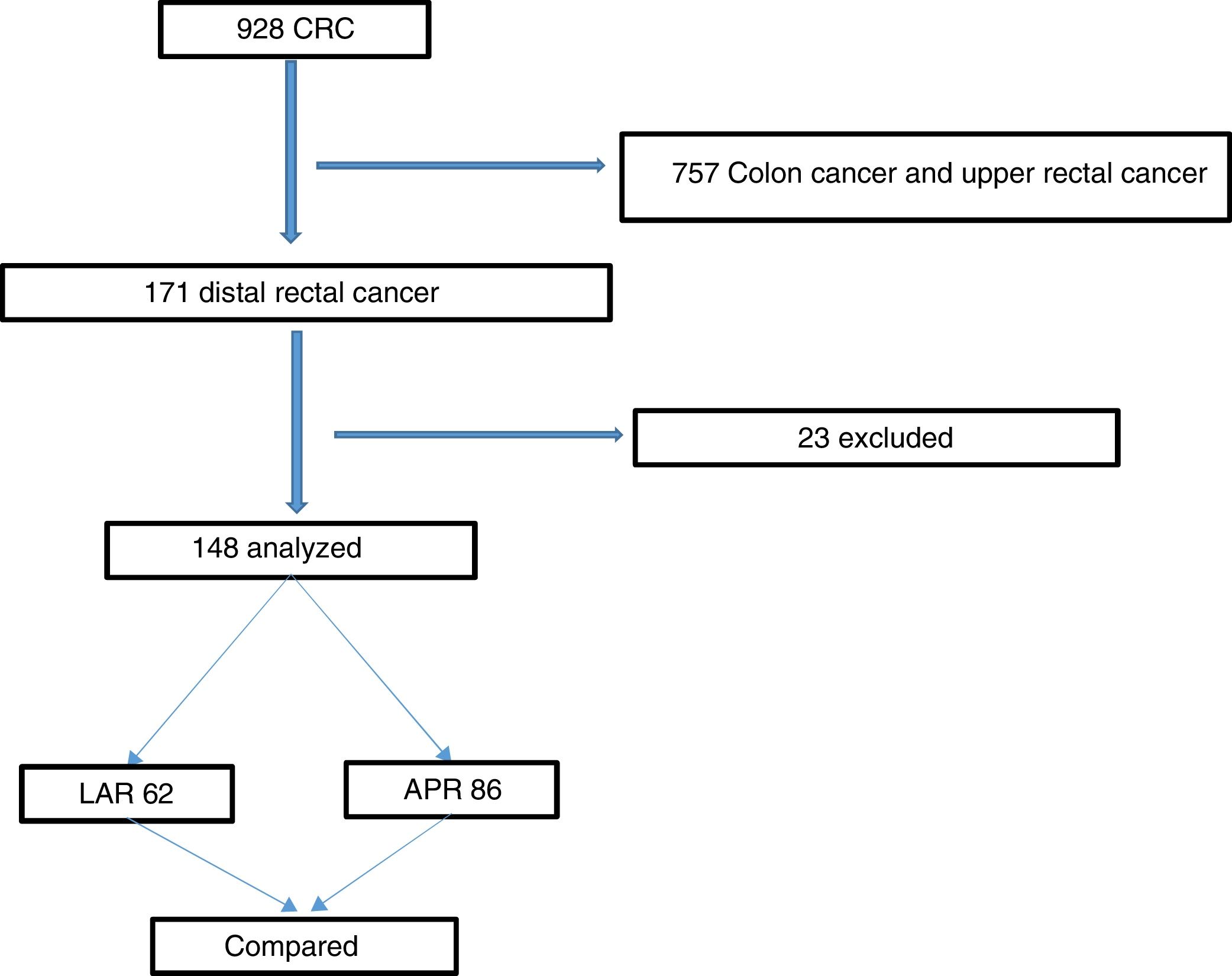

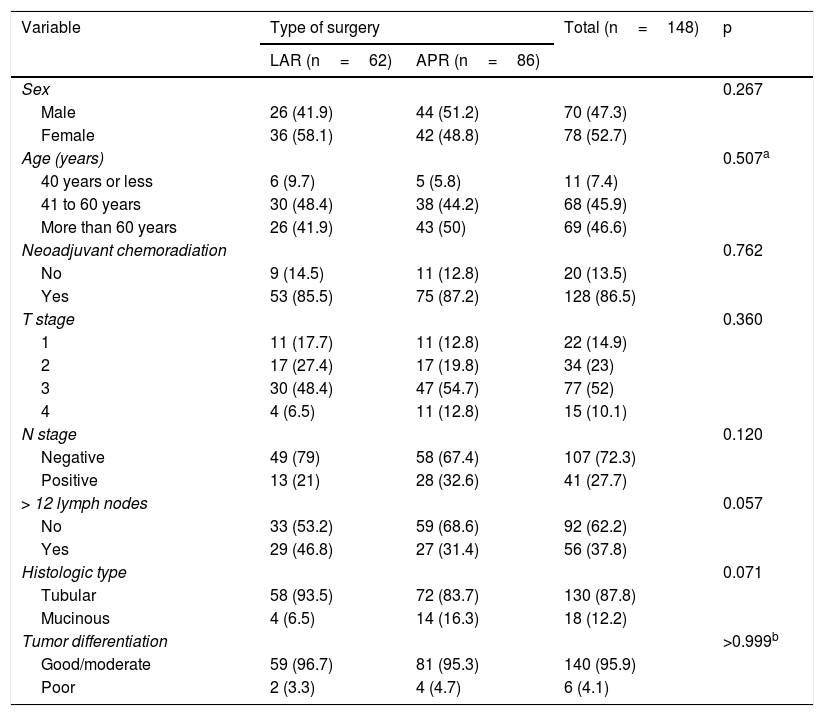

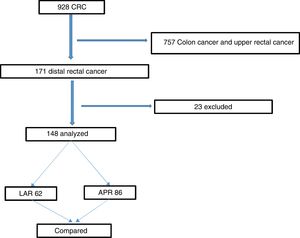

ResultsThe study was approved by the hospital’s IRB. The flowchart in Fig. 1 summarizes the inclusion and exclusion processes and the selection of distal rectal cancer patients that underwent either LAR or APR, for their comparison. Among the 928 patients that underwent surgery for colorectal cancer, 171 (18%) had cancer in the lower rectum. Twenty-three patients were excluded, leaving a total of 148 study patients. Seventy-eight of the patients were female (52.7%), and the mean patient age was 61.2 years. Regarding the surgical procedures, 62 (41.9%) patients underwent LAR, and 86 (58.1%) patients underwent APR. Table 1 summarizes and compares the parameters between the LAR and APR groups and the total number of patients studied. A total of 128 (86.5%) patients were treated with NCRT prior to surgery, and 20 (13.5%) patients were eligible for surgical treatment upfront. Most patients had locally advanced rectal cancer, with 62.1% of patients with stages T3 and T4. In addition, 41 (27.7%) patients had compromised LNs. Comparison between the groups revealed no statistically significant differences regarding the variables analyzed (Table 1). Laparoscopy was utilized in 58% of our procedures.

Patient and tumor characteristics according to the type of surgery.

| Variable | Type of surgery | Total (n=148) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAR (n=62) | APR (n=86) | |||

| Sex | 0.267 | |||

| Male | 26 (41.9) | 44 (51.2) | 70 (47.3) | |

| Female | 36 (58.1) | 42 (48.8) | 78 (52.7) | |

| Age (years) | 0.507a | |||

| 40 years or less | 6 (9.7) | 5 (5.8) | 11 (7.4) | |

| 41 to 60 years | 30 (48.4) | 38 (44.2) | 68 (45.9) | |

| More than 60 years | 26 (41.9) | 43 (50) | 69 (46.6) | |

| Neoadjuvant chemoradiation | 0.762 | |||

| No | 9 (14.5) | 11 (12.8) | 20 (13.5) | |

| Yes | 53 (85.5) | 75 (87.2) | 128 (86.5) | |

| T stage | 0.360 | |||

| 1 | 11 (17.7) | 11 (12.8) | 22 (14.9) | |

| 2 | 17 (27.4) | 17 (19.8) | 34 (23) | |

| 3 | 30 (48.4) | 47 (54.7) | 77 (52) | |

| 4 | 4 (6.5) | 11 (12.8) | 15 (10.1) | |

| N stage | 0.120 | |||

| Negative | 49 (79) | 58 (67.4) | 107 (72.3) | |

| Positive | 13 (21) | 28 (32.6) | 41 (27.7) | |

| > 12 lymph nodes | 0.057 | |||

| No | 33 (53.2) | 59 (68.6) | 92 (62.2) | |

| Yes | 29 (46.8) | 27 (31.4) | 56 (37.8) | |

| Histologic type | 0.071 | |||

| Tubular | 58 (93.5) | 72 (83.7) | 130 (87.8) | |

| Mucinous | 4 (6.5) | 14 (16.3) | 18 (12.2) | |

| Tumor differentiation | >0.999b | |||

| Good/moderate | 59 (96.7) | 81 (95.3) | 140 (95.9) | |

| Poor | 2 (3.3) | 4 (4.7) | 6 (4.1) | |

APR: abdominoperineal resection; LAR: low anterior resection.

Chi-square test.

Overall mortality at 30 days was 2.7%, with 3 (3.4%) deaths in the APR group and 1 (1.6%) death in the LAR group. There were no significant differences between the groups. All parameters analyzed between the LAR and APR groups were not significantly associated with 30-day mortality.

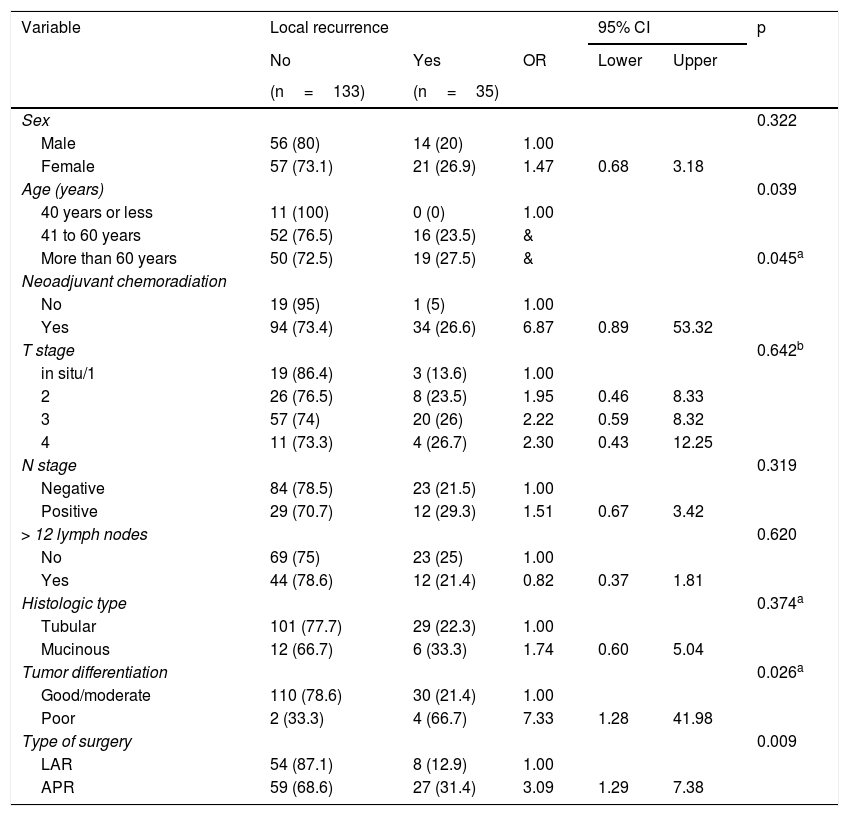

Table 2 compares local recurrence in all the parameters analyzed, including the type of surgery. In the univariate analysis, patients above 40 years of age (p=0.039), the use of neoadjuvant chemoradiation (p=0.045), poorly differentiated tumors (p=0.026), and patients that underwent APR (p=0.009) presented a significantly higher risk of local recurrence. The multivariate analysis revealed that the patients with poorly differentiated tumors presented a 7.51-times greater chance of local recurrence than the patients exhibiting good/moderate tumor differentiation (p=0.028). In addition, the patients that underwent APR presented a 2.95-times higher chance of local recurrence than the patients that underwent LAR (p=0.018).

Local recurrence according to patient and tumor characteristics.

| Variable | Local recurrence | 95% CI | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | OR | Lower | Upper | ||

| (n=133) | (n=35) | |||||

| Sex | 0.322 | |||||

| Male | 56 (80) | 14 (20) | 1.00 | |||

| Female | 57 (73.1) | 21 (26.9) | 1.47 | 0.68 | 3.18 | |

| Age (years) | 0.039 | |||||

| 40 years or less | 11 (100) | 0 (0) | 1.00 | |||

| 41 to 60 years | 52 (76.5) | 16 (23.5) | & | |||

| More than 60 years | 50 (72.5) | 19 (27.5) | & | 0.045a | ||

| Neoadjuvant chemoradiation | ||||||

| No | 19 (95) | 1 (5) | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 94 (73.4) | 34 (26.6) | 6.87 | 0.89 | 53.32 | |

| T stage | 0.642b | |||||

| in situ/1 | 19 (86.4) | 3 (13.6) | 1.00 | |||

| 2 | 26 (76.5) | 8 (23.5) | 1.95 | 0.46 | 8.33 | |

| 3 | 57 (74) | 20 (26) | 2.22 | 0.59 | 8.32 | |

| 4 | 11 (73.3) | 4 (26.7) | 2.30 | 0.43 | 12.25 | |

| N stage | 0.319 | |||||

| Negative | 84 (78.5) | 23 (21.5) | 1.00 | |||

| Positive | 29 (70.7) | 12 (29.3) | 1.51 | 0.67 | 3.42 | |

| > 12 lymph nodes | 0.620 | |||||

| No | 69 (75) | 23 (25) | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 44 (78.6) | 12 (21.4) | 0.82 | 0.37 | 1.81 | |

| Histologic type | 0.374a | |||||

| Tubular | 101 (77.7) | 29 (22.3) | 1.00 | |||

| Mucinous | 12 (66.7) | 6 (33.3) | 1.74 | 0.60 | 5.04 | |

| Tumor differentiation | 0.026a | |||||

| Good/moderate | 110 (78.6) | 30 (21.4) | 1.00 | |||

| Poor | 2 (33.3) | 4 (66.7) | 7.33 | 1.28 | 41.98 | |

| Type of surgery | 0.009 | |||||

| LAR | 54 (87.1) | 8 (12.9) | 1.00 | |||

| APR | 59 (68.6) | 27 (31.4) | 3.09 | 1.29 | 7.38 | |

APR: abdominoperineal resection; CI: confidence interval; LAR: low anterior resection; OR: odds ratio.

Chi-square test.

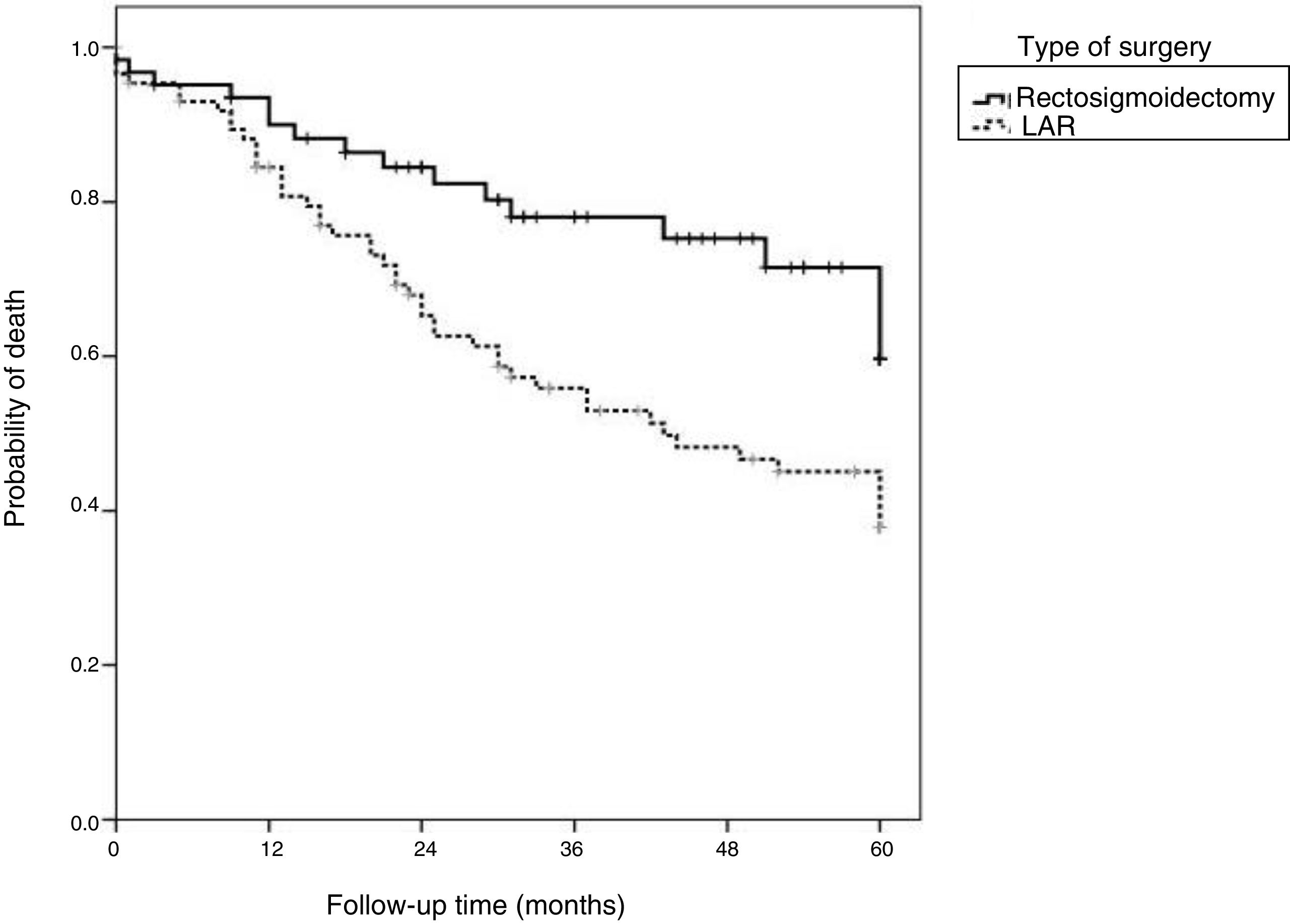

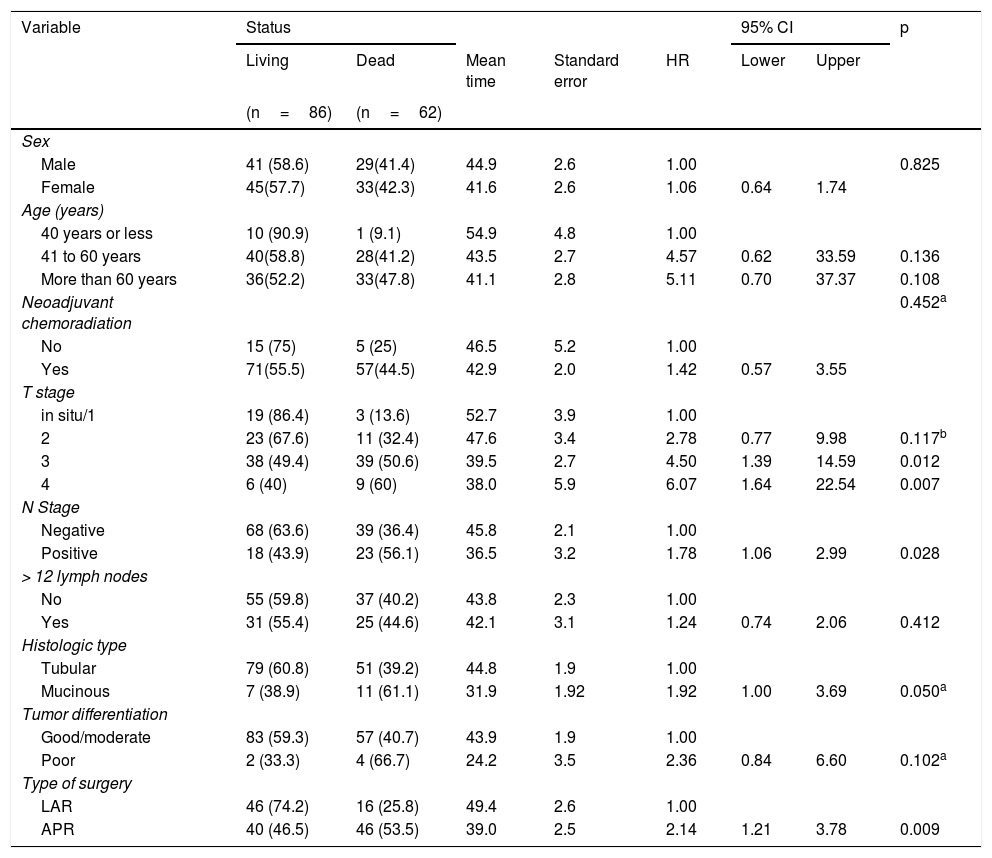

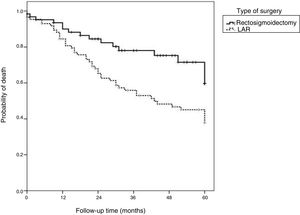

Overall 5-year survival was 58.1%. When stratified based on the type of surgery, the survival rate was lower in the APR group (46.5%) than in the LAR group (74.2%) (p=0.009).

The median follow-up time was 32 months (16 to 59.5 months). Table 3 shows that advanced T stage, N-positive stage, mucinous histologic type, and APR surgery correlated with higher risks of mortality (p<0.05). The logistic regression model revealed that the patients with T3 disease had a 4.63-times higher risk of death (p=0.011) and the patients with T4 disease had a 6.12-times higher risk of death (p=0.007) than the patients with T1/T2 disease. Additionally, the patients that underwent APR presented a 2.14-times greater risk of death than the patients that underwent LAR (p=0.009).

Overall mortality and survival calculations, according to patient and tumor characteristics.

| Variable | Status | 95% CI | p | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Living | Dead | Mean time | Standard error | HR | Lower | Upper | ||

| (n=86) | (n=62) | |||||||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 41 (58.6) | 29(41.4) | 44.9 | 2.6 | 1.00 | 0.825 | ||

| Female | 45(57.7) | 33(42.3) | 41.6 | 2.6 | 1.06 | 0.64 | 1.74 | |

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| 40 years or less | 10 (90.9) | 1 (9.1) | 54.9 | 4.8 | 1.00 | |||

| 41 to 60 years | 40(58.8) | 28(41.2) | 43.5 | 2.7 | 4.57 | 0.62 | 33.59 | 0.136 |

| More than 60 years | 36(52.2) | 33(47.8) | 41.1 | 2.8 | 5.11 | 0.70 | 37.37 | 0.108 |

| Neoadjuvant chemoradiation | 0.452a | |||||||

| No | 15 (75) | 5 (25) | 46.5 | 5.2 | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 71(55.5) | 57(44.5) | 42.9 | 2.0 | 1.42 | 0.57 | 3.55 | |

| T stage | ||||||||

| in situ/1 | 19 (86.4) | 3 (13.6) | 52.7 | 3.9 | 1.00 | |||

| 2 | 23 (67.6) | 11 (32.4) | 47.6 | 3.4 | 2.78 | 0.77 | 9.98 | 0.117b |

| 3 | 38 (49.4) | 39 (50.6) | 39.5 | 2.7 | 4.50 | 1.39 | 14.59 | 0.012 |

| 4 | 6 (40) | 9 (60) | 38.0 | 5.9 | 6.07 | 1.64 | 22.54 | 0.007 |

| N Stage | ||||||||

| Negative | 68 (63.6) | 39 (36.4) | 45.8 | 2.1 | 1.00 | |||

| Positive | 18 (43.9) | 23 (56.1) | 36.5 | 3.2 | 1.78 | 1.06 | 2.99 | 0.028 |

| > 12 lymph nodes | ||||||||

| No | 55 (59.8) | 37 (40.2) | 43.8 | 2.3 | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 31 (55.4) | 25 (44.6) | 42.1 | 3.1 | 1.24 | 0.74 | 2.06 | 0.412 |

| Histologic type | ||||||||

| Tubular | 79 (60.8) | 51 (39.2) | 44.8 | 1.9 | 1.00 | |||

| Mucinous | 7 (38.9) | 11 (61.1) | 31.9 | 1.92 | 1.92 | 1.00 | 3.69 | 0.050a |

| Tumor differentiation | ||||||||

| Good/moderate | 83 (59.3) | 57 (40.7) | 43.9 | 1.9 | 1.00 | |||

| Poor | 2 (33.3) | 4 (66.7) | 24.2 | 3.5 | 2.36 | 0.84 | 6.60 | 0.102a |

| Type of surgery | ||||||||

| LAR | 46 (74.2) | 16 (25.8) | 49.4 | 2.6 | 1.00 | |||

| APR | 40 (46.5) | 46 (53.5) | 39.0 | 2.5 | 2.14 | 1.21 | 3.78 | 0.009 |

APR: abdominoperineal resection; CI: confidence interval; LAR: low anterior resection; OR: odds ratio. Mean calculation using the Kaplan-Meier method; Bivariate proportional hazard Cox regression.

Chi-square test.

Fig. 2 shows that the patients that underwent LAR with TME presented higher overall survival rates than the patients that underwent APR.

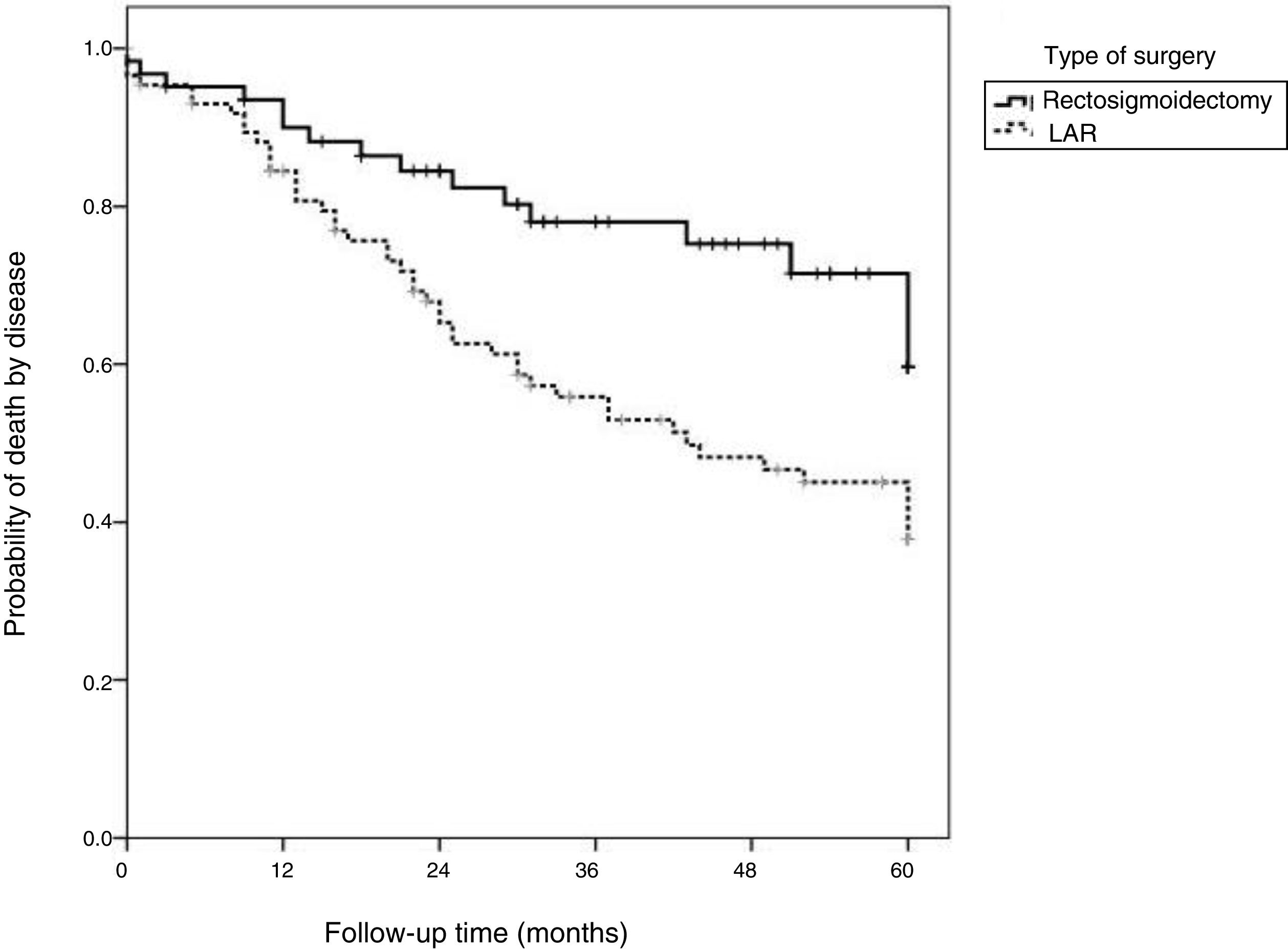

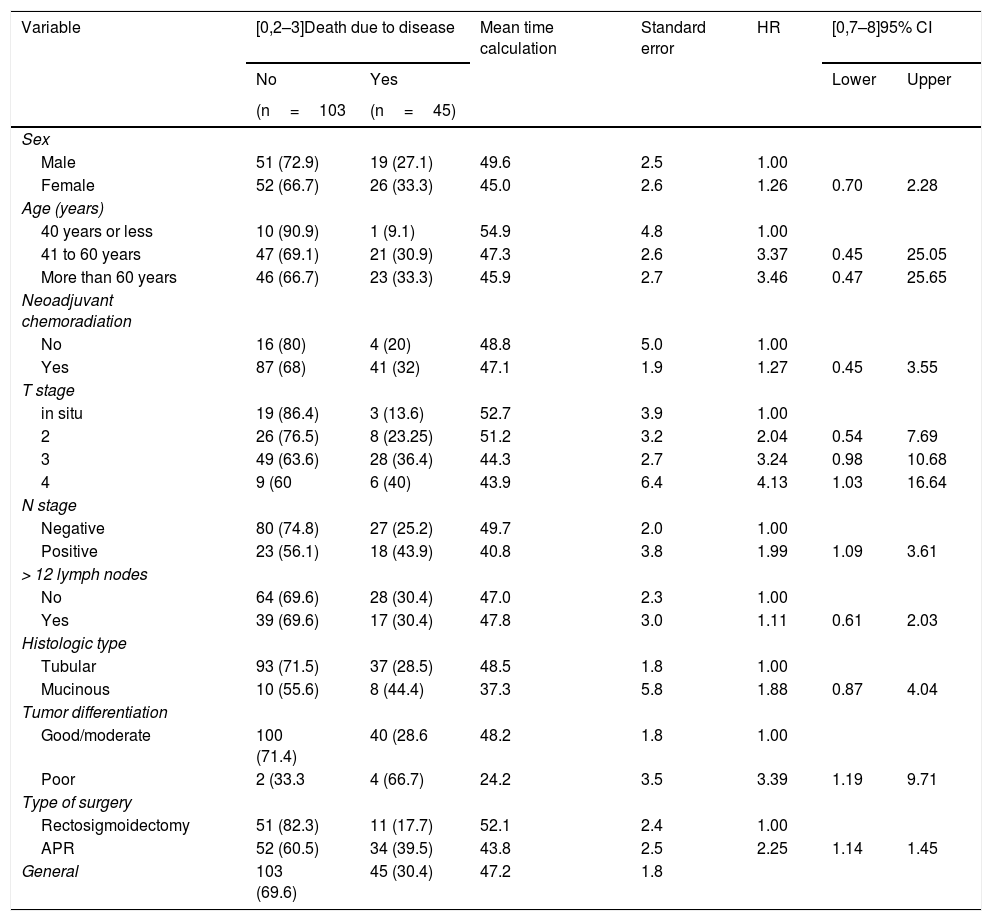

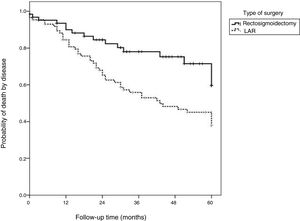

Table 4 shows that the patients with advanced T stage, lymph node involvement, and poor tumor differentiation, as well as those that underwent APR surgery, presented significantly lower disease-free survival rates (p<0.05). The logistic regression model showed that the patients with advanced T stage had a higher risk of disease-related death, with a 4.5-times higher risk in patients with T3 disease (p=0.041) and a 6.08-times higher risk in patients with T4 disease (p=0.028). The patients with poorly differentiated tumors had a 3.16-times higher risk of disease-related death than those with good/moderately differentiated tumors (p=0.034). Moreover, APR presented a 2.17-times greater risk of disease-related death than LAR (p=0.027).

Description of mortality due to disease and survival calculations, according to personal and tumor characteristics and results of statistical tests.

| Variable | [0,2–3]Death due to disease | Mean time calculation | Standard error | HR | [0,7–8]95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | Lower | Upper | ||||

| (n=103 | (n=45) | ||||||

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 51 (72.9) | 19 (27.1) | 49.6 | 2.5 | 1.00 | ||

| Female | 52 (66.7) | 26 (33.3) | 45.0 | 2.6 | 1.26 | 0.70 | 2.28 |

| Age (years) | |||||||

| 40 years or less | 10 (90.9) | 1 (9.1) | 54.9 | 4.8 | 1.00 | ||

| 41 to 60 years | 47 (69.1) | 21 (30.9) | 47.3 | 2.6 | 3.37 | 0.45 | 25.05 |

| More than 60 years | 46 (66.7) | 23 (33.3) | 45.9 | 2.7 | 3.46 | 0.47 | 25.65 |

| Neoadjuvant chemoradiation | |||||||

| No | 16 (80) | 4 (20) | 48.8 | 5.0 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 87 (68) | 41 (32) | 47.1 | 1.9 | 1.27 | 0.45 | 3.55 |

| T stage | |||||||

| in situ | 19 (86.4) | 3 (13.6) | 52.7 | 3.9 | 1.00 | ||

| 2 | 26 (76.5) | 8 (23.25) | 51.2 | 3.2 | 2.04 | 0.54 | 7.69 |

| 3 | 49 (63.6) | 28 (36.4) | 44.3 | 2.7 | 3.24 | 0.98 | 10.68 |

| 4 | 9 (60 | 6 (40) | 43.9 | 6.4 | 4.13 | 1.03 | 16.64 |

| N stage | |||||||

| Negative | 80 (74.8) | 27 (25.2) | 49.7 | 2.0 | 1.00 | ||

| Positive | 23 (56.1) | 18 (43.9) | 40.8 | 3.8 | 1.99 | 1.09 | 3.61 |

| > 12 lymph nodes | |||||||

| No | 64 (69.6) | 28 (30.4) | 47.0 | 2.3 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 39 (69.6) | 17 (30.4) | 47.8 | 3.0 | 1.11 | 0.61 | 2.03 |

| Histologic type | |||||||

| Tubular | 93 (71.5) | 37 (28.5) | 48.5 | 1.8 | 1.00 | ||

| Mucinous | 10 (55.6) | 8 (44.4) | 37.3 | 5.8 | 1.88 | 0.87 | 4.04 |

| Tumor differentiation | |||||||

| Good/moderate | 100 (71.4) | 40 (28.6 | 48.2 | 1.8 | 1.00 | ||

| Poor | 2 (33.3 | 4 (66.7) | 24.2 | 3.5 | 3.39 | 1.19 | 9.71 |

| Type of surgery | |||||||

| Rectosigmoidectomy | 51 (82.3) | 11 (17.7) | 52.1 | 2.4 | 1.00 | ||

| APR | 52 (60.5) | 34 (39.5) | 43.8 | 2.5 | 2.25 | 1.14 | 1.45 |

| General | 103 (69.6) | 45 (30.4) | 47.2 | 1.8 | |||

APR: abdominoperineal resection; CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio.

Mean calculation using the Kaplan-Meier method; Bivariate proportional hazard Cox regression.

Fig. 3 shows that disease-free survival was also higher in the patients that underwent LAR (82.3%) than those that underwent APR (60.5%).

DiscussionThe present study showed that APR surgery, alone, was independently associated with prognosis in relation to recurrence, overall survival, and disease-free survival in the multivariate Cox regression analysis. In addition, some factors were associated with worse oncologic outcomes in those patients: advanced T and N stages and poorly differentiated tumors.

APR is considered the standard operation for low rectal cancer. However, at present, APR is often performed, even though there is an insufficient distal rectal margin, resulting in a permanent stoma, which may negatively impact the patient’s quality of life.9 In addition, recent studies have shown that APR has a higher local recurrence rate, poorer survival rate, higher tumor perforation rate, and higher involvement of circumferential resection margin than LAR.10 Fortunately, APR has been less frequently performed due to improvements in surgical techniques, the application of NCRT, and changes in the acceptance of a distal resection margin of 1cm or less as a tolerable limit.10

Modern oncologic surgery concepts aim to achieve more than just curative resection of the rectal tumor mass. The quality of life of patients with rectal cancer has become a factor in primary treatment and has been equally assessed along with surgical outcomes.11

Increasing consideration for quality of life in rectal cancer treatment, technical advances in surgery, and multimodal treatments with NCRT have recently led to the common application of sphincter preservation techniques.12–17

APR is therefore considered only when sphincter-preserving anterior resection is not feasible. Furthermore, recent reports have indicated that APR may be associated with local recurrence and inferior oncologic outcomes.14

However, the indications for APR among extraperitoneal rectal cancer patients remain high, ranging from 12 to 47%.18–24 The present study showed an even higher rate for APR of 58.1%. The study time frame from 2002 to 2012 was a period when the distal and circumferential margins were not yet well-established, and the surgical techniques were gradually being refined at our healthcare institution.

A recently published systematic review reporting the oncologic outcomes after rectal cancer treatment described a mean overall 5-year survival rate of 78.6%,17 whereas the overall survival rate in the present study was 66.9% at 32 months of follow-up. Since most of the studies included in said systematic review involved preoperative patients with lower TNM stage tumors and/or patients that did not undergo NCRT, the results of our study cannot be compared with those previously reported results. Furthermore, the rate of locally advanced rectal cancer in that report was 70%.

In the present study, poor differentiation and APR were identified as independent prognostic factors for local recurrence. Several previous studies have reported that N stage, but not T stage, predicted local recurrence and decreased survival.11,17,18

APR surgery has shown poor results in several reports, exhibiting higher local recurrence rates than those for LAR surgery.23 APR is associated with higher circumferential resection margin (CRM) involvement, which is likely attributed to worse disease in patients that underwent APR than in those that underwent LAR. APR is typically indicated for patients with worse local conditions, such as sphincter invasion or a compromised intersphincteric plane. The poor prognosis of patients with an advanced pathologic stage may explain the previous reports of poorer outcomes associated with APR surgery.24–26 However, in the present study, the patients that underwent LAR or APR had similar T and N stages, but the outcomes still favored LAR surgery over APR. LAR with TME was previously demonstrated as safe for distal margin resection, allowing the sphincter to be spared, while achieving oncologic results similar to those of APR in terms of local recurrence and survival.

Many comparison studies have investigated the clinical outcomes of APR and LAR. However, few studies have compared the oncologic outcomes between APR and sphincter preservation surgery following NCRT. In the present study, the overall survival rate was 74.2% for the patients treated with LAR and 46.5% for the patients treated with APR, which is consistent with previous studies.18,24 Wibe et al.27 reported that the overall 5-year survival rate also differed between the two groups (LAR 68% vs APR 55%, p=0.001). Law et al.28 reported that survival was worse in the patients that underwent APR than in the patients that underwent LAR. Those authors further suggested that more radical resection at the level of the tumor might be necessary when performing APR. However, Chuwa and Seow-Choen24 noted that the oncologic outcomes of patients that underwent APR were not different from those that underwent LAR. In contrast with the results of the present study, those authors suggested that both APR and LAR could have similar morbidity and mortality rates, without compromising oncologic outcomes, when performed at a specialized unit.

The local recurrence rate in the present study was worse in the APR group (27%) than in the LAR group (12.9%). Wibe et al.27 also reported that the 5-year local recurrence rate was poorer in APR patients than in LAR patients (LAR 10% vs APR 15%, p=0.008). Moreover, Kim et al.18 reported that the local recurrence rate was worse in patients that underwent APR than in those that underwent LAR. However, Chuwa and Seow-Choen24 did not observe any difference in the local recurrence rate between patients treated with APR and those treated with LAR.

The present study had several limitations. First, due to the retrospective design of the study, selection bias might have affected the results, and hidden confounding factors could have been missed. Another limitation was the fact that although all the patients underwent a standard TME, the grading of its completeness was not recorded in our database during the early study period. Thus, we were unable to report on the grading of TME quality. The measurement methods employed can also be responsible for differences in distal resection margin lengths and we did not include the stapled donut ring, which might have affected distal margin length.

ConclusionThe patients with locally advanced distal rectal cancer that underwent APR presented with lower overall and disease-related survival and a higher rate of local recurrence than the patients that underwent LAR.

In addition, advanced T stage, compromised lymph nodes, and poor tumor differentiation were associated with local recurrence and lower disease-free survival, regardless of the surgical procedure.

Authors and contributionsNahas S. C.: Project conception, creation of the database for patient evaluation, and final manuscript revision.

Nahas C. S. R.: Study design, data analysis, and manuscript revision.

Bustamante-Lopez L.A.: Drafting of the texts and literature review.

Pinto R. A.: Data collection and drafting of the manuscript.

Marques C. F. S.: Data analysis and manuscript revision.

Cecconello I.: Lead author that supervised the entire work and revised the final document.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Nahas CSR, Bustamante-Lopez LA, Pinto RA, Marques CFS, Cecconello I. Desenlaces de tratamiento quirúrgico para pacientes con cáncer de recto distal: Una revisión retrospectiva en un hospital universitario. Revista de Gastroenterología de México. 2020;85:180–189.