The differential diagnosis of proctitis in men who have sex with men (MSM) tends to be difficult, given that it includes numerous infectious, inflammatory, and even traumatic causes. Lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) is a sexually transmitted disease caused by Chlamydia trachomatis (C. trachomatis). It usually manifests first as an ulcerated, painless papule in the genitals, then as inguinal lymphadenopathy, and finally as distal proctitis.1 In relation to late diagnosis, disease progression can result in severe complications, such as rectal stricture, obstruction, and perforation.1,2

We present herein a 35-year-old patient, with a history of HIV diagnosed in 2012 in relation to Epstein Barr-associated meningitis, currently treated with highly effective antiretroviral therapy with raltegravir 400 mg and tenofovir/emtricitabine 300/200 mg. He had a CD4+ lymphocyte count of 248 cells and an undetectable viral load, and in addition, was identified as an asymptomatic carrier of hepatitis B infection.

He was admitted to the hospital due to clinical symptoms of intense pain in the rectoanal region of 3-month progression, painful defecation, straining, and tenesmus, associated with frequent episodes of rectal bleeding. In the systems review, the patient stated having occasional fever peaks, asthenia, adynamia, hyporexia, myalgias, and arthralgias.

Upon physical examination, the presence of pain in the hypogastrium, with no peritoneal irritation, stood out. The perianal evaluation revealed a deep posterior anal fissure, with marked edema of the anal canal. No adenopathies were palpated in the inguinal region, nor were there lesions on the skin. Due to the patient’s medical history, coinfection with other sexually transmitted diseases or opportunistic infections was ruled out. A VDRL test and IgM for Epstein-Barr virus were ordered, along with rectosigmoidoscopy, to evaluate the mucosa and anal canal and take biopsies.

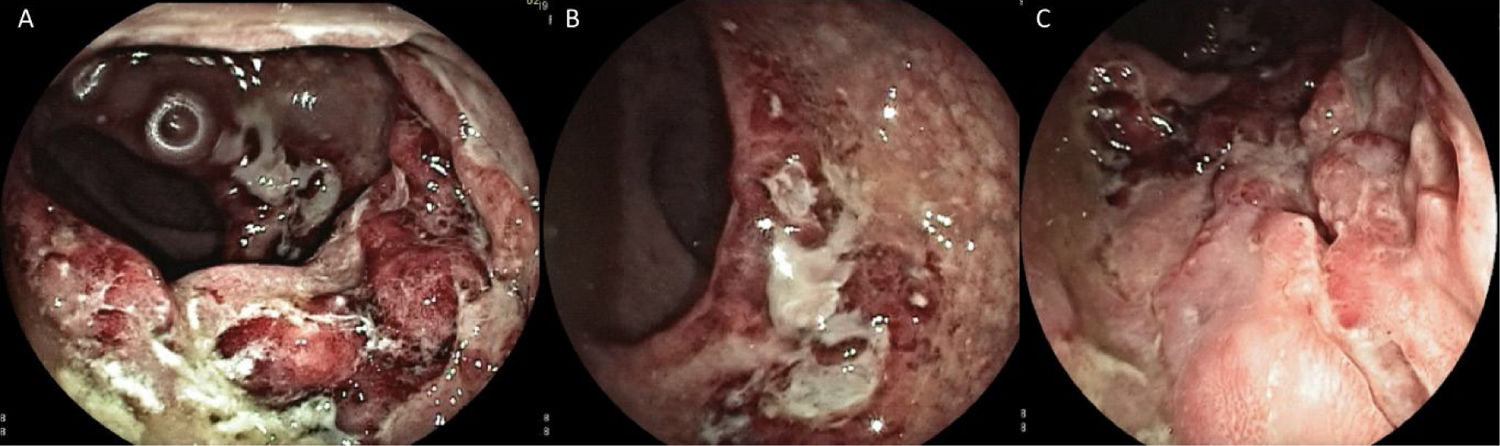

The rectosigmoidoscopy revealed severe inflammatory changes and deep inflammatory ulcers with irregular edges that compromised the middle and distal rectum, with anal canal involvement (Fig. 1A-C). Biopsies were taken to identify the causal agent. Included in the pathology study was abundant lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate of the mucosa, with no viral cytopathic changes, with atrophy, and no dysplasia. Direct testing with techniques for mycobacteria, cytomegalovirus, and fungi was negative, as were the Thayer-Martin agar for Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection and the PCR for fungi and mycobacteria, and so PCR in C. trachomatis tissue was ordered. The VDRL serologic test for syphilis was reactive at 16 dilutions. Thus, in addition to treatment with 100 mg, every 12 h, of oral doxycycline, 2.4 million units of benzathine penicillin was administered weekly for 3 weeks.

A) Rectosigmoidoscopy showing the severe inflammatory changes on the first and second Houston’s valves: marked edema, erythema, and deep, fibrin-covered ulcer. B) Severe inflammatory involvement in the distal rectum, with obvious edema and mucosal thickening. C) Deformity and deep ulcer at the level of the distal rectum, with irregular edges and a sharply demarcated aspect, with anal canal involvement.

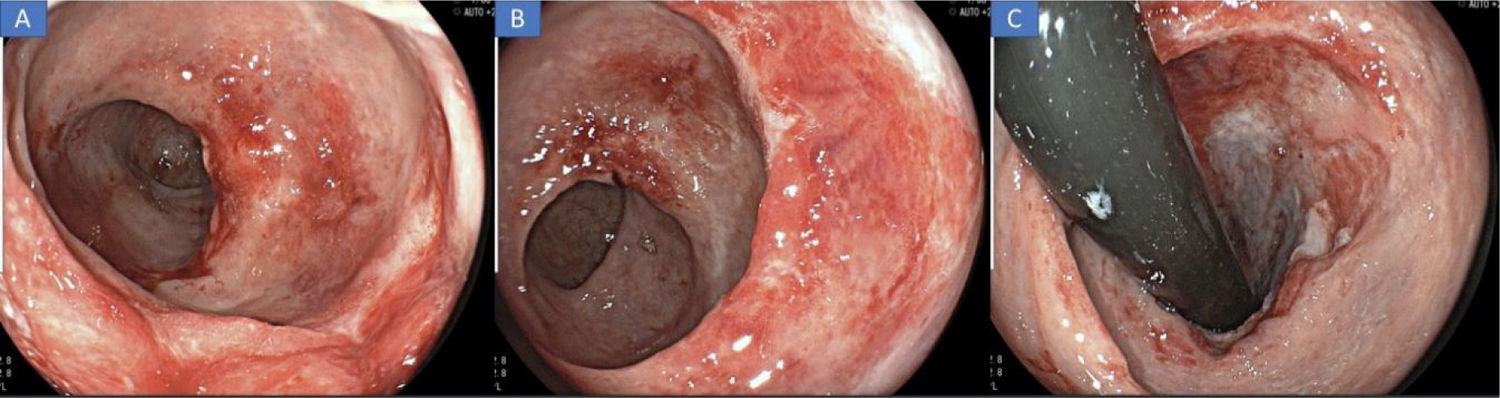

Two weeks later, the patient was readmitted to the emergency service for abdominal pain, with scant rectal bleeding. A computed axial tomography scan and rectosigmoidoscopy were ordered. The first image ruled out perforation and associated collections. The rectosigmoidoscopy revealed significant improvement of the inflammatory changes, as well as ulcers in the process of healing (Fig. 2A-C). After symptom control, the patient was released and completed the treatment with doxycycline in 21 days.

A) Rectosigmoidoscopy showing notable improvement of the inflammatory changes 2 weeks after treatment: first and second Houston’s valves. B) Notable improvement of the inflammatory changes in the distal rectum. C) Retroflexion of the rectum, showing the mucosal cicatrization, as well as improvement in the findings close to the anal canal.

Infectious proctitis in MSM, especially those with a history of HIV, is varied. The most frequent pathogens are Neisseria gonorrhoeae, C. trachomatis, the herpes simplex virus, and Treponema pallidum.2,3 In an Australian study, differences in the prevalence of the causal agents of infectious proctitis in MSM were found, according to their immune status.3 The most frequent causal agent was the herpes simplex virus in men that had a history of HIV infection, whereas LGV was the most frequent in men that were HIV-negative. No statistically significant differences related to HIV status regarding symptoms were found in that study. LGV proctitis is characterized by a purulent anal discharge, straining, tenesmus, painful defecation, and altered bowel habit. On occasion, there can be fever, general malaise, weight loss, rectal bleeding, or hematochezia. In a Spanish study that analyzed anorectal manifestations in patients with sexually transmitted diseases, the most frequent symptoms were anal pain, painful defecation, purulent anorectal secretion, straining, tenesmus and/or rectal bleeding.4 Those authors found that LGV was present in 74% of the patients that had anorectal symptoms lasting more than 1 month, and in all the patients that had documented proctitis associated with rectal ulcers.4 Three stages of LGV are recognized: the first is characterized by the presence of painless or painful ulcers at the site of contagion that can last up to 4 weeks; in the second stage, lymphadenopathies and abscesses are formed; and in the third stage, if there has not been adequate treatment, the infection advances to include severe complications, such as fistulas, infertility, elephantiasis, or stricture.1

Endoscopic study findings range from mild inflammatory changes, deep ulcers with elevated edges and sharply demarcated morphology, and a frequently observed fibrinoid and/or mucopurulent exudate, to stricture and the appearance of tumors.5–8 Those findings can be indistinguishable from inflammatory bowel disease, adenocarcinoma, or rectal lymphoma. The most frequent biopsy findings are granulation tissue with lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates and fibrosis, which are signs of nonspecific proctitis. Endoscopic findings are not specific, thus there must be a high degree of clinical suspicion in MSM that present with ulcerated proctitis, to be complemented with nucleic acid amplification through PCR testing from secretions or samples of affected tissue, even in the presence of other sexually transmitted diseases.9

Ethical considerationsThe present work complies with the current bioethical research norms and was approved by the institutional ethics committee.

Data confidentialityWritten informed consent was not requested, given that the data were carefully protected. There are no clinical history or imaging data that allow the patient of the clinical case to be identified.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that the present article contains no personal information that could identify the patient.

Financial disclosureNo financial support was received in relation to this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Mosquera-Klinger G, Berrio S, Carvajal JJ, Juliao-Baños F, Ruiz M. Proctitis ulcerada asociada a linfogranuloma venéreo. Rev Gastroenterol Méx. 2021;86:313–315.