Liver position abnormalities or the presence of ectopic liver tissue are considered rare entities that are asymptomatic, incidental findings. Incidence is from 0.24 to 0.56%, according to case reports in laparoscopic surgery and autopsy results.1

Reported sizes vary from millimeters to centimeters. Collan et al. classified them into four types: type 1, an ectopic liver not connected to the mother liver but to the bladder or abdominal ligaments; type 2, microscopic ectopic liver frequently found on the bladder wall; type 3, large accessory hepatic lobe joined to the mother liver by a pedicle; and type 4, small hepatic lobe joined to the mother liver.2

An ectopic liver implies exposure to factors that predispose to carcinogenesis. An incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma is reported in 30% of cases and is commonly related to vascular and biliary tree abnormalities.3,4

There are only two case reports in the literature on an intrahepatic gallbladder in a pelvic liver. The two patients were diagnosed incidentally and had a history of omphalocele repair in infancy. In those cases, the right and left hepatic ducts joined to form the common hepatic duct that took a cranial direction to enter into the duodenal ampulla in the habitual location.5,6 We present herein the case of an ectopic liver with an intrahepatic biliary tree located in the pelvis that was found incidentally during the approach in managing female infertility.

Clinical caseA 23-year-old female patient under study for female infertility was referred from the gynecology department for a gastroenterology evaluation to rule out liver disease due to abnormal structures incidentally found in an abdominal ultrasound carried out as part of the female infertility protocol. The pertinent personal pathologic history included abdominal wall repair due to gastroschisis in infancy and a spontaneous abortion at six weeks of gestation, two years prior. The rest of the past medical history was unremarkable. Physical examination revealed the presence of abdominal scarring along the mid-line, peristalsis, a slightly mobile, well-delineated, palpable mass in the hypogastrium, with smooth, regular edges, that was nonpainful upon palpation, with dull sounds upon percussion. Laboratory tests included liver function tests that reported total bilirubin 0.8 mg/dl, alkaline phosphatase 46 mg/dl, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) 75 mg/dl, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 27 mg/dl, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 36 mg/dl, and albumin 4.1 mg/dl.

The abdominal ultrasound report stated: “hepatic gland with notable increase in its dimensions, showing homogeneous echogenicity and echotexture and no intrahepatic or extrahepatic biliary tree dilation. The choledochus measures 2.5 mm and the portal vein has an interior diameter of 5 mm. The gallbladder has a thin wall, and its interior is anechoic; the pancreas cannot be evaluated due to overlapping of the bowel segments. The right kidney cannot be evaluated at this time, and only the right renal fossa was located. Diagnostic impression: grade III hepatomegaly, probable agenesis vs. right renal ectopia.”

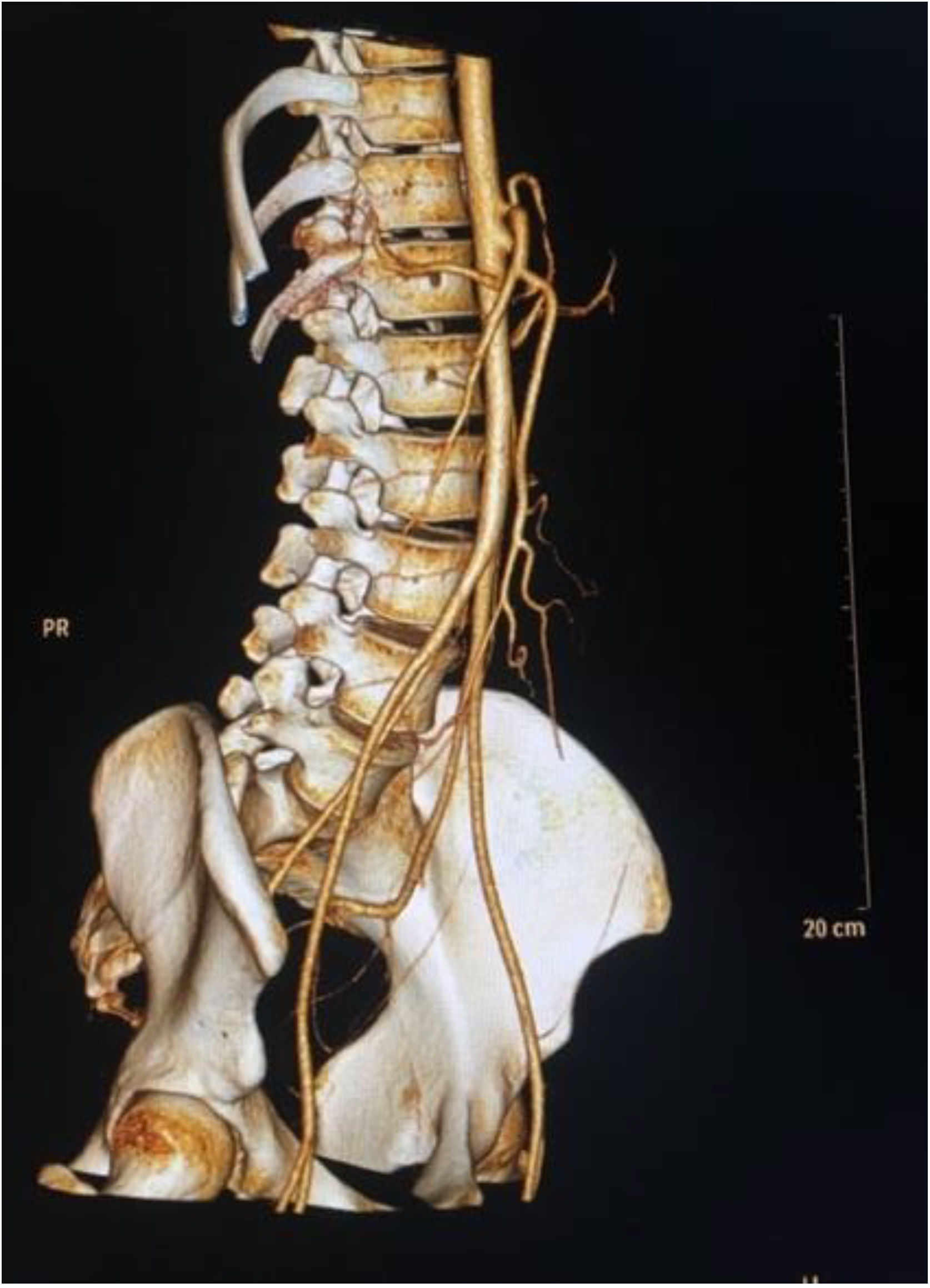

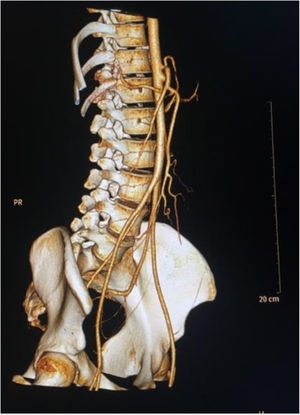

Due to the data found in the initial imaging study, abdominal-pelvic angiotomography was ordered. In the simple phase, it showed absence of the liver in the right hypochondrium and location of the liver in the hypogastrium along the pelvis, with a maximum diameter of 187 mm and the presence of a Riedel lobe as an anatomic variant (Fig. 1). Both kidneys were displaced at the level of the diaphragm and the pancreas was rounded. In the arterial phase with maximum intensity projection (MIP) and volume rendering technique (VRT) reconstructions (Fig. 2), absence of the celiac trunk is shown, finding the solitary proximal emergence of the splenic artery and the distal emergence of the hepatic artery, which was subdivided into right and left arteries. The superior mesenteric artery had no alterations in its course or diameter. Magnetic cholangioresonance showed intrahepatic biliary integrity.

Hepatic tissue can migrate to different sites during embryogenesis. The errant liver is described as asymptomatic but has also been described as a cause of intra-abdominal bleeding and malignancy.1 It is a rare condition resulting after the repair of congenital defects of the abdominal wall.

During the gynecologic approach, an ovarian hormone profile was carried out and was within normal parameters. The imaging studies revealed integrity of the ovaries and uterus. Given that no lesions were identified and there were no liver function test alterations, a liver biopsy was not performed, and we concluded that metabolic liver function was normal. The case has been followed for one year and the patient has not achieved pregnancy, nor has she presented with complications related to liver function.

After a review of the literature, we found case reports on patients diagnosed with gastroschisis and ectopic liver. However, we found no direct association of infertility with an errant liver, given that there are no case reports of said relation in the literature, even though infertility evaluation led to the discovery of that variant in our patient.

Many considerations need to be taken into account in relation to the present case. We are facing a little-known area with respect to the course a pregnancy, if viable, could take under these circumstances, as well as the effect the product could have on the liver. Thus, greater evidence on the topic is needed, as well as on the association between the two entities.

Ethical considerationsNo experiments were conducted on animals or humans in relation to this research. The patient gave her informed consent to publish her clinical data. The present study was authorized by the ethics department of the Hospital General De Occidente for the review of the data and images obtained from the case report, following the current regulations on data protection and research on humans contemplated in the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. No identifying data, images, or personal data of the patient were used. The patient authorized the presentation of this case report through informed consent.

Financial disclosureNo financial support was received in relation to this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Montoya-Montoya O, Palomino-Ayala S, Santana-Montes MO. Hígado ectópico intrapélvico como causa excepcional de infertilidad femenina: Reporte de un caso. Rev Gastroenterol México. 2021;86:311–313.