Helicobacter pylori causes motor, secretory, and inflammatory gastrointestinal disorders and therefore the term “functional” has been questioned when referring to dyspepsia associated with this bacterium. Patients with dyspepsia and Helicobacter pylori infection could have clinical characteristics that differentiate them a priori from those with true functional dyspepsia.

AimsTo determine whether there are clinical differences between patients with functional dyspepsia and Helicobacter pylori-associated dyspepsia that enable their a priori identification and to know the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with functional dyspepsia.

Patients and methodsA total of 578 patients with dyspepsia with no significant lesions detectable through endoscopy were divided into 2 groups according to the presence of Helicobacter pylori. The clinical characteristics, medical history, comorbidities, and use of health resources were compared between the two groups. A sub-analysis pairing the groups by age and sex in a 1:1 ratio was carried out to reduce bias.

ResultsA total of 336 patients infected with Helicobacter pylori were compared with 242 non-infected patients. The prevalence of infection in the patients with dyspeptic symptoms and no endoscopically detectable lesions was 58%. The initial analysis showed that the cases with dyspepsia and Helicobacter pylori infection were more frequently associated with overweight, obesity, high blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, and metabolic syndrome, but the paired analysis nullified all these differences.

ConclusionsThe patients with dyspepsia infected with Helicobacter pylori had similar clinical characteristics to the non-infected patients and could not be differentiated a priori. The prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with functional dyspepsia was 58% and increased with age.

El Helicobacter pylori (Hp) causa trastornos motores, secretores e inflamatorios gastrointestinales por lo que el término «funcional» ha sido puesto en duda cuando se refiere a dispepsia asociada a la bacteria. Los enfermos con dispepsia infectados por Hp podrían tener características clínicas que podrían diferenciarlos a priori de los funcionales.

ObjetivosDeterminar si existen diferencias clínicas entre los pacientes con dispepsia funcional (DF) y dispepsia asociada a Hp que permitan identificarlos a priori y conocer la prevalencia de infección por Hp en pacientes con DF.

Pacientes y métodosQuinientos setenta y ocho pacientes con dispepsia sin lesiones significativas detectables por endoscopia fueron divididos en 2 grupos de acuerdo con la presencia de Hp. Se compararon las características clínicas, los antecedentes médicos, las comorbilidades y el uso de recursos de salud entre ambos grupos. Se realizó un subanálisis pareando los grupos por edad y sexo en proporción 1:1 para reducir el efecto de sesgos.

ResultadosSe comparó a 336 infectados por Hp y 242 no infectados. La prevalencia de la infección en pacientes con síntomas dispépticos sin lesiones detectables por endoscopia fue del 58%. El análisis inicial mostró que los casos con dispepsia infectados por Hp se asociaron con mayor frecuencia a sobrepeso, obesidad, hipertensión arterial, diabetes mellitus y síndrome metabólico, pero el análisis pareado anuló todas estas diferencias.

ConclusionesLos pacientes con dispepsia infectados por Hp muestran características clínicas similares a los no infectados y no pueden ser diferenciados a priori. La prevalencia de infección por Hp en pacientes con DF es del 58% y se incrementa con la edad.

Dyspepsia is one of the most common digestive syndromes in the general population and is defined as the presence of discomfort or chronic and recurrent pain in the upper abdomen.1 It has been described as a negative sensation that can incorporate a wide variety of symptoms including bloating, early satiety, fullness, burping, nausea, or continuous or intermittent vomiting.2 This set of symptoms can be the manifestation of different organic, systemic, or metabolic diseases (organic dyspepsia) or it may have no evident cause (functional dyspepsia [FD]). Thus, dyspepsia encompasses a heterogeneous group of diseases whose clinical manifestations are common, but are caused by different pathophysiologic mechanisms.3

Helicobacter pylori (Hp) is the most frequent cause of chronic bacterial infection in humans.4 Its prevalence varies from 20 to 90%, depending on conditions of development and hygiene.5 Its prevalence is very high in Mexico and in other Latin American countries with similar sociodemographic characteristics.6 The reported prevalence of Hp infection in patients with FD varies from 30 to 70%.7

It is known that Hp can cause dyspeptic symptoms, inducing motor disorders, causing visceral hypersensitivity, acid secretion alterations, active and persistent inflammation, and post-infectious changes in the gastroduodenal mucosa.8,9 By definition, functional gastrointestinal disorders are characterized by the absence of organic, metabolic, or systemic diseases that explain their symptoms. One notable exception to this rule is Hp infection that is included in FD according to the Rome III criteria.10 Given that the bacterium can directly or indirectly cause motor, secretory, and inflammatory disorders, the term “functional” has been questioned in regard to dyspepsia associated with Hp (D-Hp).11 Knowing the clinical characteristics of the patients with dyspepsia infected with the bacterium and those without the infection would enable us to define the groups that could benefit from distinct treatments.

The primary aim of this work was to determine whether there are clinical differences between the patients with FD and D-Hp that enable its identification a priori. The secondary aim was to know the prevalence of Hp infection in patients with FD.

Patients and methodsAll the patients seen for dyspepsia that underwent first-time upper gastrointestinal endoscopy within the time frame of April 2006 and August 2015 were considered for participation in this study. Dyspepsia was defined as the presence of chronic and recurrent discomfort in the upper abdomen that included one or more of the following symptoms: epigastric pain or burning sensation, early satiety, fullness, burping, bloating, nausea, or vomiting.2

A complete and uniform anamnesis was carried out and the same physician (RCS) transferred all the information to an electronic format with pre-established text fields. The same endoscopist (RCS) also performed all the endoscopic studies at the same endoscopy unit of a single hospital center. Two biopsies were taken from the stomach (one from the body and one from the antrum) in all of the cases for the rapid urease test (Azutim®, Innovare R&D, Mexico City, Mexico). Registration (photos and video) of the endoscopic examination was obtained and a structured report stipulated the findings and the definitive diagnosis. For the purpose of this study, endoscopic findings, such as gastric mucosa with erythema, pale areas, nodularity, reticular pattern, or vascular pattern visualization, were considered normal in the absence of erosive, ulcerated, or neoplastic lesions.

Those patients presenting with heartburn and regurgitation as the only symptoms or the predominant ones or with abdominal pain that improved after a bowel movement, were excluded from the study. All patients with alarm symptoms or suspicion of organic disease, such as dysphagia, significant involuntary weight loss (> 10% of the habitual weight within the last 6 months), anemia, gastrointestinal bleeding in any clinical presentation, those patients in whom endoscopy or biopsy was contraindicated, patients that had taken acid secretion inhibitors or antibiotics in the 2 weeks prior to endoscopy, and those that had any type of esophageal, gastric, or duodenal surgery were also excluded from the study.

All patients in whom erosions, ulcers, or neoplasia in any portion of the esophagus, stomach, or duodenum were detected, were eliminated from the study. Patients with diminutive gastric polyps (fewer than 5 and smaller than 5mm) were included in the study, as long as they did not present with mucosal lesions. All patients that did not have a complete clinical case record were also eliminated from the study.

Two groups were formed in accordance with the result of the rapid urease test: those patients with dyspepsia that had Hp infection (Hp group) and those with dyspepsia and no Hp infection (non-Hp group). The following clinical characteristics were compared between the two groups: sex, age, a family history of organic and functional gastrointestinal diseases, smoking, alcohol consumption, a past history of abdominal or esthetic surgeries, and a history of allergies. Hospital admissions and emergency department visits were also registered, along with psychiatric attention and the use of psychotropic drugs during the year prior to the endoscopic study. Finally, body mass index, the frequency of concomitant diseases, and drug use at the time of the endoscopy were compared between the groups. The World Health Organization's definition of metabolic syndrome was utilized.12

According to the set of predominant dyspeptic symptoms at the time of evaluation, the patients were classified as having epigastric pain syndrome if they presented with pain or burning sensation or both in the upper abdomen and as having postprandial distress syndrome if they presented with early satiety or fullness or both. Those patients that had all the symptoms, none of which was predominant, were classified as having overlap syndrome.

Statistical analysisThe clinical data were obtained from the case record and endoscopic report and recorded on a data collection sheet and placed in a database (Excel, Microsoft). The descriptive data were expressed as percentages, means, and ranges. The chi-square test and Fisher's exact test were used for the comparative analysis and were calculated utilizing the Epi Info application for the iPad (Epi Info™ version 2.0.2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA). All p values above 0.05 were not considered significant. The odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval were also calculated when deemed necessary. In order to prevent the influence of selection bias on some of the factors, a sub-analysis was carried out pairing the groups by age and sex at a 1:1 ratio. Two hundred and fifteen subjects were included in each group for this sub-analysis.

ResultsA total of 1038 patients with no prior endoscopic evaluation were seen for dyspeptic symptoms during the study period. Three hundred and seven patients were excluded (198 for presenting with heartburn and acid regurgitation as predominant symptoms, 96 for presenting with an alarm symptom or sign of organic disease, and 13 for esophageal, gastric, or duodenal surgery). One hundred and fifty-three patients were eliminated (85 for detection of erosions, ulcers, or neoplasias and 68 for having incomplete clinical case records).

A total of 578 patients with dyspepsia and no significant lesions detected at endoscopy were included in the final analysis: 336 cases infected with Hp (Hp group) and 242 cases without the infection (non-Hp group), resulting in a 58.1% prevalence of infection with the bacterium in patients with dyspeptic symptoms and no significant lesions detected at endoscopy. A similar number of patients in both groups were studied for treatment-refractory dyspepsia (76.2% infected with Hp vs 77.5% without Hp, p=NS), whereas the rest had unstudied dyspepsia (23.8% infected with Hp vs 22.3% without Hp, p=NS). The mean progression time of the dyspeptic symptoms reported by the patients was similar in both groups (43.2 months in the patients infected with Hp vs 42.8 months in those without Hp, p=NS).

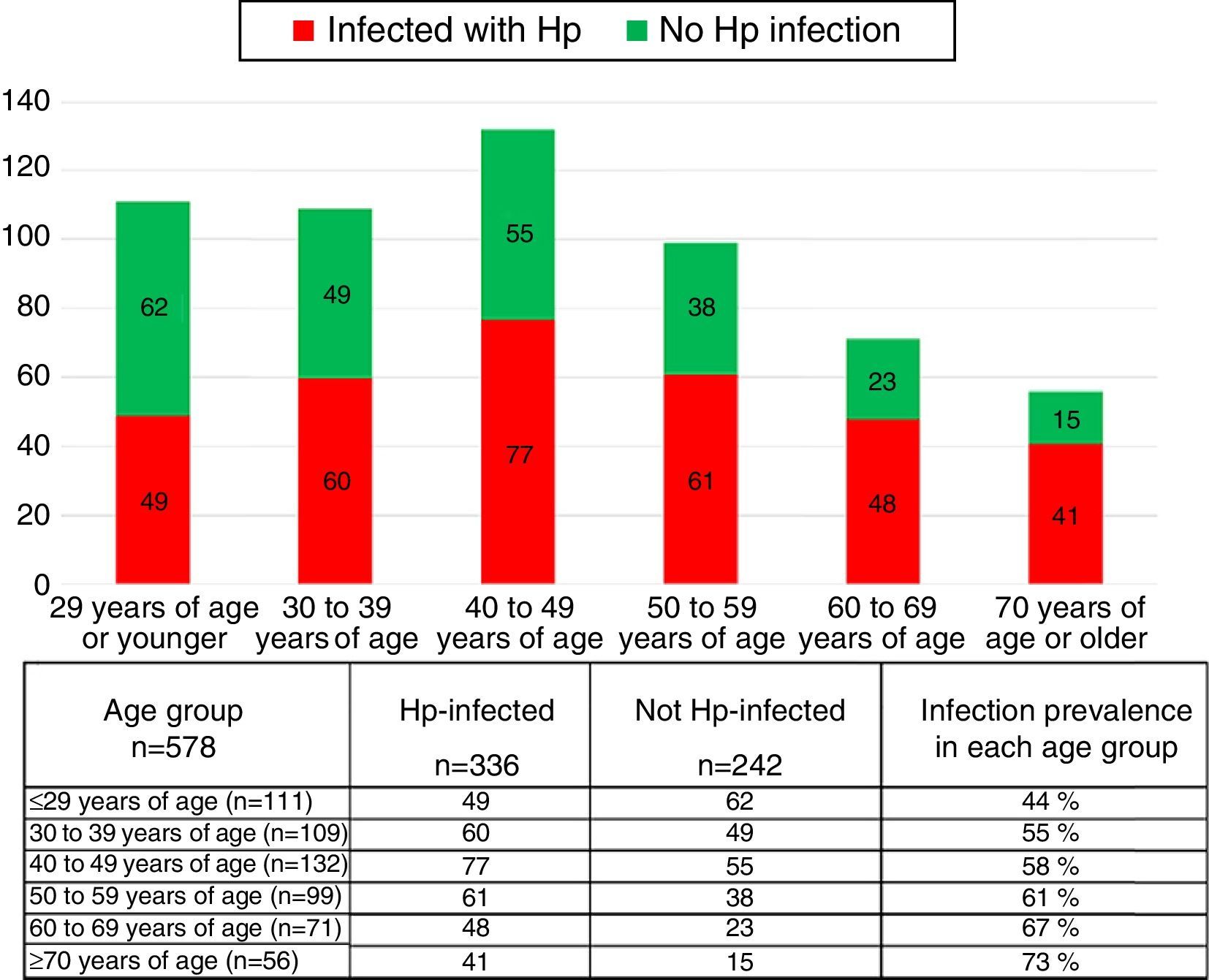

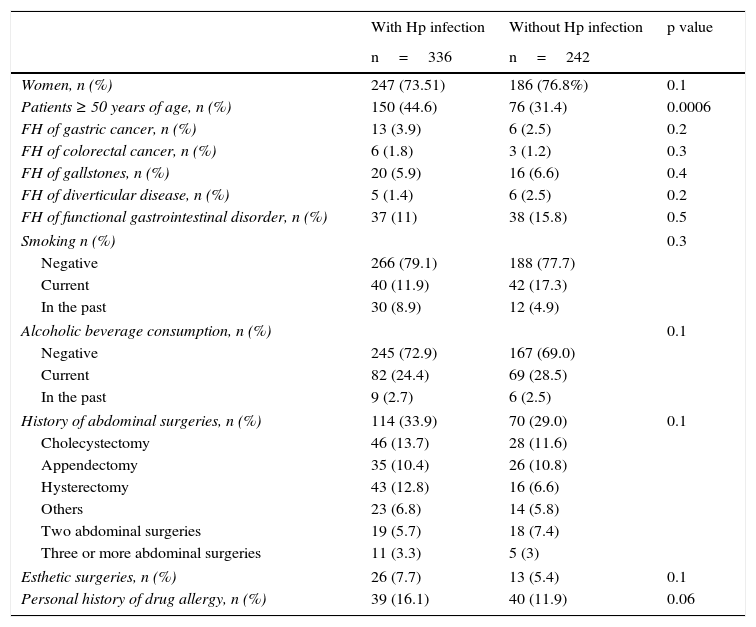

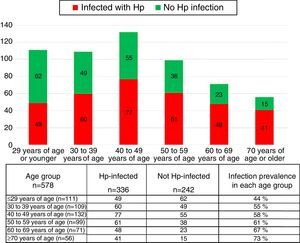

The group of cases infected with the bacterium had a higher mean age (48.08 years in the patients with Hp infection vs 42.46 years in those without Hp). There were a greater number of patients 50 years old, or older, in the Hp group compared with the non-Hp group (44.6 vs 31.4% respectively, p=0.0006, RR 1.25 [1.09-1.43]). Hp infection prevalence rose as patient age increased (fig. 1). The prevalence of Hp infection in patients under 29 years of age was 44%, it was 55% in the group between 30 and 39 years of age, 58% in those between the ages of 40 and 49 years, 61% in the patients between 50 and 59 years of age, 67% in those between the ages of 60 and 69 years, and 73% in the patients over 70 years of age. No significant differences were observed between the groups in relation to distribution by sex, the prevalence of a family history of known functional and organic gastrointestinal diseases, smoking, alcohol consumption, a personal history of abdominal surgeries, esthetic surgeries, or a history of allergies (Table 1).

General demographic characteristics, family history, and non-pathologic personal history.

| With Hp infection | Without Hp infection | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n=336 | n=242 | ||

| Women, n (%) | 247 (73.51) | 186 (76.8%) | 0.1 |

| Patients ≥ 50 years of age, n (%) | 150 (44.6) | 76 (31.4) | 0.0006 |

| FH of gastric cancer, n (%) | 13 (3.9) | 6 (2.5) | 0.2 |

| FH of colorectal cancer, n (%) | 6 (1.8) | 3 (1.2) | 0.3 |

| FH of gallstones, n (%) | 20 (5.9) | 16 (6.6) | 0.4 |

| FH of diverticular disease, n (%) | 5 (1.4) | 6 (2.5) | 0.2 |

| FH of functional gastrointestinal disorder, n (%) | 37 (11) | 38 (15.8) | 0.5 |

| Smoking n (%) | 0.3 | ||

| Negative | 266 (79.1) | 188 (77.7) | |

| Current | 40 (11.9) | 42 (17.3) | |

| In the past | 30 (8.9) | 12 (4.9) | |

| Alcoholic beverage consumption, n (%) | 0.1 | ||

| Negative | 245 (72.9) | 167 (69.0) | |

| Current | 82 (24.4) | 69 (28.5) | |

| In the past | 9 (2.7) | 6 (2.5) | |

| History of abdominal surgeries, n (%) | 114 (33.9) | 70 (29.0) | 0.1 |

| Cholecystectomy | 46 (13.7) | 28 (11.6) | |

| Appendectomy | 35 (10.4) | 26 (10.8) | |

| Hysterectomy | 43 (12.8) | 16 (6.6) | |

| Others | 23 (6.8) | 14 (5.8) | |

| Two abdominal surgeries | 19 (5.7) | 18 (7.4) | |

| Three or more abdominal surgeries | 11 (3.3) | 5 (3) | |

| Esthetic surgeries, n (%) | 26 (7.7) | 13 (5.4) | 0.1 |

| Personal history of drug allergy, n (%) | 39 (16.1) | 40 (11.9) | 0.06 |

FH: Family history.

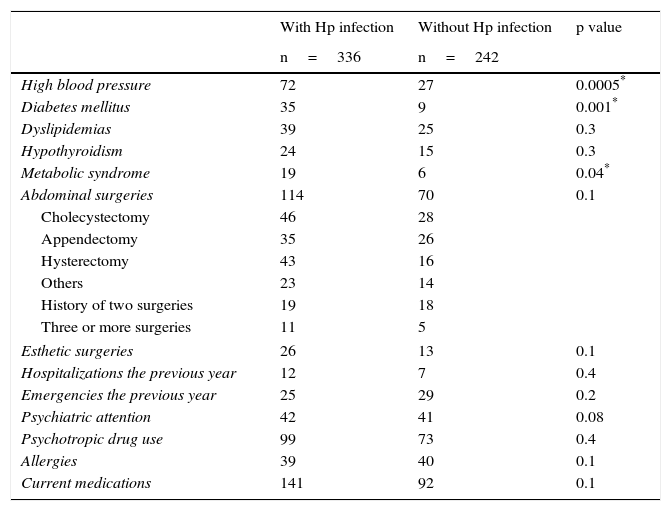

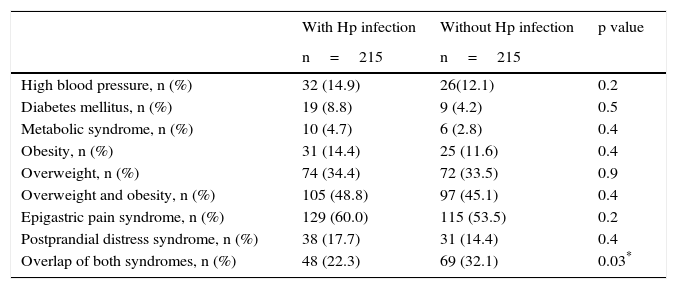

There was a greater frequency in the Hp group of overweight, obesity, high blood pressure, and diabetes mellitus (Table 2). The prevalence of metabolic syndrome was greater in the Hp group compared with the non-Hp group (5.7% vs 2.5%, respectively, p=0.04). However, all these differences disappeared when the analysis was paired by age and sex (Table 3). No significant differences were observed between the groups in relation to hospital admissions, emergency department visits, psychiatric attention, or psychotropic drug use in the year prior to the endoscopy study (Table 2).

Prevalence of associated comorbidities, pathologic personal history, medical service use, and medication consumption.

| With Hp infection | Without Hp infection | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n=336 | n=242 | ||

| High blood pressure | 72 | 27 | 0.0005* |

| Diabetes mellitus | 35 | 9 | 0.001* |

| Dyslipidemias | 39 | 25 | 0.3 |

| Hypothyroidism | 24 | 15 | 0.3 |

| Metabolic syndrome | 19 | 6 | 0.04* |

| Abdominal surgeries | 114 | 70 | 0.1 |

| Cholecystectomy | 46 | 28 | |

| Appendectomy | 35 | 26 | |

| Hysterectomy | 43 | 16 | |

| Others | 23 | 14 | |

| History of two surgeries | 19 | 18 | |

| Three or more surgeries | 11 | 5 | |

| Esthetic surgeries | 26 | 13 | 0.1 |

| Hospitalizations the previous year | 12 | 7 | 0.4 |

| Emergencies the previous year | 25 | 29 | 0.2 |

| Psychiatric attention | 42 | 41 | 0.08 |

| Psychotropic drug use | 99 | 73 | 0.4 |

| Allergies | 39 | 40 | 0.1 |

| Current medications | 141 | 92 | 0.1 |

Analysis of the prevalence of comorbidities and dyspeptic syndromes paired by age and sex (1:1).

| With Hp infection | Without Hp infection | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n=215 | n=215 | ||

| High blood pressure, n (%) | 32 (14.9) | 26(12.1) | 0.2 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 19 (8.8) | 9 (4.2) | 0.5 |

| Metabolic syndrome, n (%) | 10 (4.7) | 6 (2.8) | 0.4 |

| Obesity, n (%) | 31 (14.4) | 25 (11.6) | 0.4 |

| Overweight, n (%) | 74 (34.4) | 72 (33.5) | 0.9 |

| Overweight and obesity, n (%) | 105 (48.8) | 97 (45.1) | 0.4 |

| Epigastric pain syndrome, n (%) | 129 (60.0) | 115 (53.5) | 0.2 |

| Postprandial distress syndrome, n (%) | 38 (17.7) | 31 (14.4) | 0.4 |

| Overlap of both syndromes, n (%) | 48 (22.3) | 69 (32.1) | 0.03* |

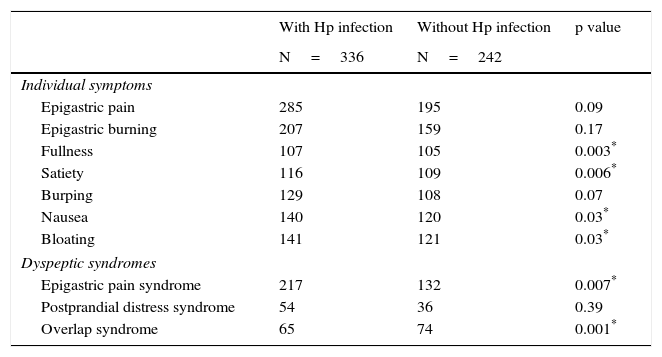

Upon individual symptom evaluation, there was no difference between the groups in regard to the prevalence of epigastric pain, epigastric burning sensation, burping, or bloating, even though the patients with Hp presented less frequently with fullness, early satiety, and nausea compared with the non-Hp patients (Table 4). In the analysis of the predominant symptoms together, there was a greater frequency of epigastric pain syndrome between the patients infected with the bacterium compared with those not infected (64.6 vs 54.4%, respectively, p=0.01, RR 1.51, 95% CI 1.08-2.13), the prevalence of postprandial distress syndrome was similar in the two groups (16.1% cases vs 14.9% controls, p=NS), and there was a greater number of subjects in the non-Hp group that presented with overlap of both syndromes (19.3% of the cases vs 30.6% of the controls, p=0.002) (Table 4). Nevertheless, the analysis paired by age and sex showed a similar prevalence between the groups in relation to epigastric pain syndrome (60% with Hp vs 53.5% without Hp, p=NS) and postprandial distress syndrome (17.7% with Hp vs 14.4% without Hp, p=NS). There was a higher number of overlap of both syndromes in the non-Hp group (22.3% with Hp vs 32.1% without Hp, p=0.03, OR 0.6, 95% CI=0.39-0.93) (Table 3).

Prevalence of dyspeptic symptoms and syndromes.

| With Hp infection | Without Hp infection | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N=336 | N=242 | ||

| Individual symptoms | |||

| Epigastric pain | 285 | 195 | 0.09 |

| Epigastric burning | 207 | 159 | 0.17 |

| Fullness | 107 | 105 | 0.003* |

| Satiety | 116 | 109 | 0.006* |

| Burping | 129 | 108 | 0.07 |

| Nausea | 140 | 120 | 0.03* |

| Bloating | 141 | 121 | 0.03* |

| Dyspeptic syndromes | |||

| Epigastric pain syndrome | 217 | 132 | 0.007* |

| Postprandial distress syndrome | 54 | 36 | 0.39 |

| Overlap syndrome | 65 | 74 | 0.001* |

The endoscopic findings were similar in the two groups. Hiatal hernia was detected in 11 cases and in 14 controls (3.3% vs 5.8%, respectively, p=NS), diminutive hyperplastic gastric polyps in 13 cases and 16 controls (3.9% vs 6.6% respectively, p=NS), and a duodenal submucosal nodule in one case and duodenal lymphangiectasia in one control.

DiscussionThe present study shows that the clinical characteristics in the patients with FD infected with Hp were similar to those of non-infected patients, and therefore they could not be differentiated or identified a priori. Our study also found a prevalence of Hp infection in patients with FD of 58% that increased with patient age.

Functional gastrointestinal disorders are defined by the absence of organic, metabolic, or systemic diseases that explain their symptoms. One notable exception to this rule is Hp infection that is included in FD according to the Rome III criteria despite the fact that it causes motor, secretory, and inflammatory disorders.10 Thus, the term “functional” has been questioned in reference to dyspepsia associated with Hp infection.11 On the other hand, the eradication of the bacterium has been shown to be effective treatment in at least one subgroup of patients with dyspepsia,13 and therefore the clinical identification of those patients with Hp infection could enable the definition of groups that would benefit from specific treatments.

It has been inferred that the inflammation produced by the bacterium can cause pain, and its presence and intensity could be an indicator of infection. Tucci et al. found that epigastric pain and burning sensation were significantly more intense in patients with dyspepsia infected with the bacterium than in those not infected.14 However, the relation is not solid, given that some studies have reported an association between the grade of inflammation and pain intensity,15,16 but others have not been able to establish any correlation.17,18 Similarly, several studies have demonstrated that the bacterium induces motility and gastric emptying disorders, but these changes have not resulted in specific or distinctive symptom patterns.19–21 In the present study, the initial data analysis showed that a greater number of patients with dyspepsia infected with the bacterium had epigastric pain syndrome, but this difference was nullified when the sub-analysis paired by age and sex was carried out.

If patients with dyspepsia and Hp infection cannot be identified through symptoms, then other factors should be explored. The initial analysis of our study showed a greater prevalence of overweight, obesity, high blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, and metabolic syndrome in the patients with dyspepsia infected with the bacterium. Some studies have found that this bacterium plays an important role in cardiometabolic disorders and its presence has recently been significantly and consistently associated with a higher body mass index, overweight, and obesity in a Chinese population.22,23 Nevertheless, this relation is not clear, given that other studies have shown an inverse relation between infection with the bacterium and prevalence of overweight and obesity in both children and adults in developed countries.24,25 Likewise, the effects of the bacterium on ghrelin secretion have not been completely explained. This peptide, which regulates appetite and body weight, has been found to be suppressed in patients with chronic Hp infection26 and its levels in plasma have increased with the microorganism's erradication,27 whereas other studies have not found significant changes in the serum levels of the peptide in relation to active infection or the eradication of the bacterium.28 Even if the presence of cardiometabolic disorders were a biomarker of dyspepsia due to Hp, the sub-analysis paired by age and sex in the present study did not confirm an association between the two factors. It is most likely that the association found was a product of bias, given that in the infected group the mean age and the number of patients older than 50 years of age was significantly higher.

Due to the fact that functional dyspepsia is related to psychologic factors and psychiatric comorbidity,29,30 it is valid to think that dyspepsia not associated with Hp infection would have a greater relation to these factors because it is a clearly functional disease. One study that investigated the presence of psychologic factors in patients with functional dyspepsia compared with patients with peptic ulcer found that functional dyspepsia patients had more severe psychologic comorbidity and psychiatric disorders than those with organic disease.31 In our study there were no differences between the groups in relation to a history of abdominal surgeries, esthetic surgeries, the need for medical attention at the emergency department, the use of psychotropic drugs, or psychiatric attention that could be indicative of associated psychologic-psychiatric comorbidity and somatization. Nor were these characteristics useful for inferring the absence or presence of the bacterium.

An interesting finding of our study was that the prevalence of Hp infection rose as patient age increased. One possible explanation of this fact could be the epidemiologic change observed worldwide in recent years. A systematic review of the epidemiology of this infection in Iran and countries to the east of the Mediterranean found that positive serology for the most virulent Hp (Cag A+) was greater as the age of the study populations increased.32 A lower prevalence of Hp has also been found in the younger generations, suggesting that the prevalence of the infection could decline in the future.33 This finding should be investigated more appropriately in the future. Our study design did not allow us to make conclusions about it.

In the present study, we compared two well-defined groups of subjects, the Hp-infected group and the non-Hp group, examining a wide variety of clinical characteristics in search of an objective indicator that would predict the presence of the bacterium. The number of cases included in the study allowed a sub-analysis paired by age and sex to be carried out, but since there was no calculation from a previous sample, we could not be certain that the absolute number obtained was sufficient for determining differences. The diagnostic methods were the same for the entire group and the same physician performed the endoscopic examinations, strengthening our study. Concomitantly, we were able to know the prevalence of the infection in patients with dyspeptic symptoms and no erosive, ulcerous, or neoplastic lesions of the proximal digestive tract. Nevertheless, this study has the methodological defects inherent in all retrospective studies of not having used validated instruments for detecting and determining digestive symptom intensity or confirming the presence or absence of infection through more than one diagnostic method. Given that there is no ideal diagnostic test for determining the presence of Hp, the combining of the results of 2 or more tests can be a reasonable diagnostic strategy for obtaining more reliable results.34,35 In the present study, the diagnosis of infection was made only through the use of a commercial urease test. If properly used, this type of test has 95-100% sensitivity and 85-95% specificity.34,35 The urease test that we employed was validated in a Mexican population and compared with another rapid urease test and histology, and its diagnostic performance was adequate.36 In addition, performing the rapid urease test utilizing 2 gastric biopsies (one from the body and the other from the antrum), which was done in our study, can improve the accuracy of the test by reducing the sampling error resulting from the non-uniform distribution of the bacterium in the stomach.34 Therefore, we consider that better designed prospective studies are required for detecting clinical characteristics in patients with dyspepsia that would enable the presence of the infection to be predicted and identified a priori.

In conclusion, this study showed that the patients with FD infected with Hp had similar clinical characteristics to those patients that were not infected, and thus they could not be differentiated a priori. There was also a 58% prevalence of Hp infection in patients with FD and the infection was observed to increase with patient age.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of persons and animalsThe authors declare that the procedures followed conformed to the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation and were in accordance with the World Medical Association and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects referred to in the article. This document is in the possession of the corresponding author.

Financial disclosureNo financial support was received in relation to this study.

Conflict of interestJosé Luis Rodríguez-García declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ramón Carmona-Sánchez is a Member of the Advisory Board of Mayoly-Spindler and a Speaker for Mayoly-Spindler and Asofarma. He is participating in a clinical research study for Laboratorios Senosiain, Mexico.

Please cite this article as: Rodríguez-García JL, Carmona-Sánchez R. Dispepsia funcional y dispepsia asociada a infección por Helicobacter pylori: ¿son entidades con características clínicas diferentes? Revista de Gastroenterología de México. 2016;82:126–133.