Malignant dysphagia is difficulty swallowing resulting from esophageal obstruction due to cancer. The goal of palliative treatment is to reduce the dysphagia and improve oral dietary intake. Self-expandable metallic stents are the current treatment of choice, given that they enable the immediate restoration of oral intake. The aim of the present study was to describe the results of using totally covered and partially covered esophageal stents for palliating esophageal cancer.

Materials and methodsA retrospective study was conducted on patients with inoperable esophageal cancer treated with self-expandable metallic stents. The 2 groups formed were: group A, which consisted of patients with a fully covered self-expandable stent (SX-ELLA®), and group B, which was made up of patients with a partially covered self-expandable stent (Ultraflex®).

ResultsOf the 69-patient total, 50 were included in the study. Group A had 19 men and 2 women and their mean age was 63.6 years (range 41-84). Technical success was achieved in 100% (n=21) of the cases and clinical success in 90.4% (n=19). Group B had 24 men and 5 women and their mean age was 67.5 years (range 43-92). Technical success was achieved in 100% (n=29) of the cases and clinical success in 89.6% (n=26). Complications were similar in both groups (33.3 vs. 51.7%).

ConclusionThere was no difference between the 2 types of stent for the palliative treatment of esophageal cancer with respect to technical success, clinical success, or complications.

La disfagia maligna es la dificultad para la deglución que resulta de la obstrucción del esófago secundaria a cáncer. Los objetivos del tratamiento paliativo son la disminución de la disfagia y mejorar la ingesta por vía oral. En la actualidad las prótesis metálicas autoexpandibles son el tratamiento de elección en virtud de que permiten restaurar de inmediato la vía oral. El objetivo de este estudio fue describir los resultados de la utilización de prótesis esofágicas totalmente cubiertas y parcialmente cubiertas para paliar el cáncer de esófago.

Material y métodosEstudio retrospectivo en pacientes con cáncer de esófago irresecable tratados con prótesis metálica autoexpandible. Se formaron 2 grupos: el grupo A incluyó pacientes con una prótesis autoexpandible totalmente cubierta (SX-ELLA®); el grupo B estuvo formado por aquellos con prótesis autoexpandible parcialmente cubierta (Ultraflex®).

ResultadosDe 69 pacientes se incluyeron 50. En el grupo A fueron 19 hombres y 2 mujeres, con una edad promedio de 63.6 años (rango 41-84). El éxito técnico y clínico se obtuvo en el 100% (n=21) y el 90.4% (n=19) de los casos, respectivamente. En el grupo B fueron 24 hombres y 5 mujeres, con una edad promedio de 67.5 años (rango 43-92). El éxito técnico y clínico se logró en el 100% (n=29) y el 89.6% (n=26) de los pacientes, respectivamente. Las complicaciones en ambos grupos fueron similares (33.3 vs. 51.7%).

ConclusiónNo existe diferencia entre los 2 tipos de prótesis para la paliación del cáncer de esófago con respecto a éxito técnico, éxito clínico y complicaciones.

Malignant dysphagia is defined as difficulty swallowing that is the result of partial or total obstruction of the esophageal lumen secondary to cancer. In patients with inoperable esophageal cancer, the palliative treatment goals are reduction of the dysphagia and improved oral intake. Self-expandable metallic stents are currently the treatment of choice because they enable immediate restoration of the oral pathway with a minimum of hospitalization, and they rarely cause severe complications. In a multicenter clinical trial, Vakil et al. compared 32 patients that received a partially covered self-expandable stent (PCSEMS) with 30 patients that had uncovered self-expandable metallic stent (UCSEMS) placement. They observed no tumor growth inside the stent in the PCSEMS group (0/32), compared with the UCSEMS group (8/30, 27%). Migration occurred in 2/30 (6.6%) of the patients with an UCSEMS and in 4/32 (12.5%) of those with a PCSEMS, but with no statistically significant difference (p = 0.44).1 Fully covered self-expandable metallic stents (FCSEMSs) have also been used before beginning neoadjuvant treatment. In the study by Siddiqui et al., 55 patients that underwent neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy utilized the ALIMAXX® (Merit Medical, South Jordan, UT, USA), Wallflex® (Microvasive Endoscopy, Natick, MA, USA), and Evolution® (Cook Endoscopy, Winston-Salem, NC, USA) FCSEMSs. They reported no cases of obstruction from tumor ingrowth, but the stent migrated in 17/55 (31%) of the patients in a mean 44 days (range: 6-154 days).2 Currently the most widely used stents for inoperable esophageal cancer palliation are the partially covered ones, regardless of their design. The aim of the present study was to describe the results of FCSEMS use, compared with PCSEMS use for esophageal cancer palliation.

Materials and methodsA retrospective study carried out within the time frame of January 2011 and June 2014 was conducted on patients above 18 years of age that had self-expandable metallic stent placement due to inoperable esophageal cancer and dysphagia. Patients with a history of total or partial esophagogastric resection and those that did not participate in the follow-up were excluded from the study. The type of stent used in each patient was based on the endoscopist's criterion. The following 2 study groups were formed: group A, which consisted of patients with FCSEMS placement (SX-ELLA®, made of nitinol, completely covered with silicone, ELLA-CS, Hradec Králové, Czech Republic), with a stent trunk diameter of 20mm and of 25mm and 24mm at the proximal and distal ends, respectively. The lengths of the stents were 85mm and 110mm; and group B, which was made up of patients that had a PCSEMS (Ultraflex® NG, Boston Scientific, partially covered with polyurethane), with an external diameter of 23mm, proximal end of 23mm and distal end of 28mm, and lengths of 100mm, 120mm, and 150mm, with coverings of 70mm, 90mm, and 120mm, respectively.

The clinical and demographic variables analyzed were: age, sex, clinical stage, BMI, dysphagia grade, dysphagia progression time, stent indication, tumor location, history of chemoradiotherapy, and complications associated with them, such as obstruction, migration, bleeding, and pain.

Definition of the variablesTechnical success was defined as the placement of the stent at least 1cm from the proximal and distal limits of the tumor. In the case of tracheoesophageal fistula, technical success additionally included the appropriate covering of the fistula opening.

Dysphagia before and after stent placement was evaluated according to the Likert scale as grade 0 (no dysphagia), grade 1 (dysphagia for solids), grade 2 (dysphagia for semisolids), grade 3 (dysphagia for liquids), or grade 4 (dysphagia for saliva).

Clinical success was regarded as dysphagia reduction of equal to or greater than 2 grades, with respect to the initial evaluation.

Tumor location: Proximal esophagus between 15 and 20cm from the incisors, middle esophagus between 21 and 30cm from the incisors, and distal esophagus between 31 and 40cm from the incisors.

Complications: all events associated with stent placement or design, such as pain, bleeding, perforation, or migration.

Early complications: those that occurred within the first 30 days after the procedure.

Late complications: those that occurred after the first 30 days of stent placement.

Statistical analysisDescriptive statistics of the variables were carried out according to the type of variable: proportions were presented for the nominal or ordinal variables and mean and standard deviation were presented for the quantitative variables. The differences between groups were evaluated using the chi-square test for the qualitative variables and the Student's t test for independent samples for the quantitative variables. Statistical significance was set at a p < 0.05.

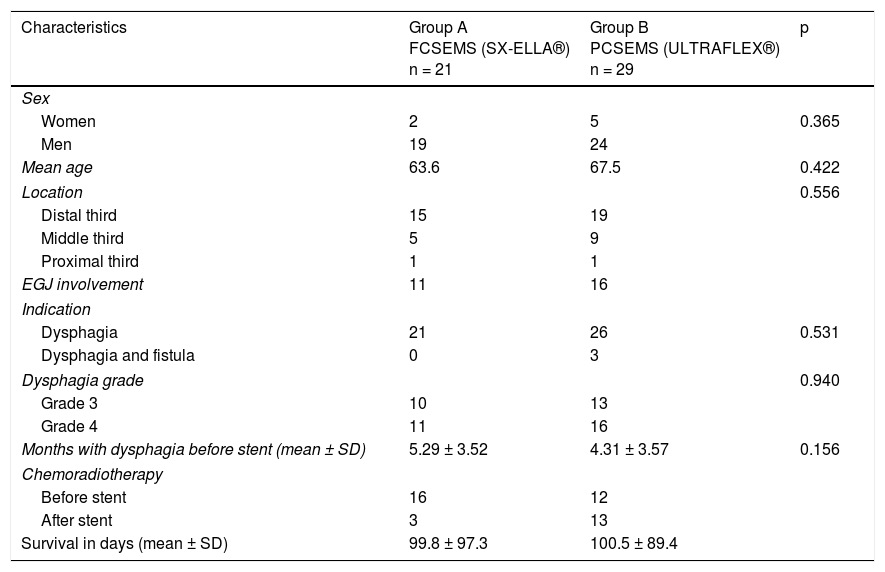

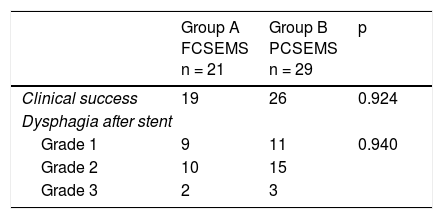

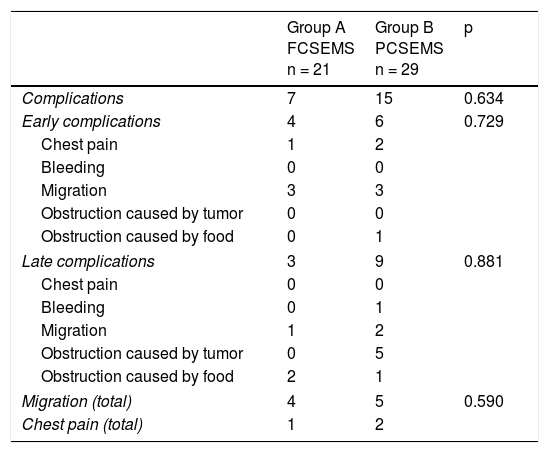

ResultsOf the 69 patients that underwent stent placement, only 50 had the stents of interest for the present study. Group A (n = 21) (Table 1) was made up of 19 men and 2 women, with a mean age of 63.6 years (range: 41-84). Stent indication was dysphagia in 100% of those cases. Ten patients (47.6%) had grade 3 dysphagia and 11 patients (52.3%) had grade 4. Mean dysphagia duration was 5.29 ± 3.52 months. Sixteen of the patients (76.1%) had chemoradiotherapy before stent placement and 3 patients (14.2%) had chemoradiotherapy after stent placement. The tumor was located in the distal third in 15 patients (71.4%), in the middle third in 5 patients (23.8%), and in the proximal third in one patient (4.7%). The tumor affected the esophagogastric junction in 11 patients (52.3%). Technical success was achieved in 21 cases (100%) and clinical success in 19 (90.4%) (Table 2). Dysphagia after stent placement was grade 1 in 9 patients (42.8%), grade 2 in 10 patients (47.6%), and grade 3 in 2 patients (9.5%) (Table 2). Complications presented in 7 cases (33.3%) (Table 3). Four patients (19%) had early complications, corresponding to migration in 3 of those patients (14.2%) and to chest pain in one of them (4.7%). Late complications presented in 3 patients (14%), one of whom presented with migration and 2 (9.5%) with obstruction caused by food. Of the complication total, there were 4 cases (19%) of stent migration. Three cases (75%) corresponded to distal tumors with esophagogastric junction involvement and one case (25%) corresponded to a tumor in the middle third of the esophagus.

Clinical and demographic characteristics.

| Characteristics | Group A FCSEMS (SX-ELLA®) n = 21 | Group B PCSEMS (ULTRAFLEX®) n = 29 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Women | 2 | 5 | 0.365 |

| Men | 19 | 24 | |

| Mean age | 63.6 | 67.5 | 0.422 |

| Location | 0.556 | ||

| Distal third | 15 | 19 | |

| Middle third | 5 | 9 | |

| Proximal third | 1 | 1 | |

| EGJ involvement | 11 | 16 | |

| Indication | |||

| Dysphagia | 21 | 26 | 0.531 |

| Dysphagia and fistula | 0 | 3 | |

| Dysphagia grade | 0.940 | ||

| Grade 3 | 10 | 13 | |

| Grade 4 | 11 | 16 | |

| Months with dysphagia before stent (mean ± SD) | 5.29 ± 3.52 | 4.31 ± 3.57 | 0.156 |

| Chemoradiotherapy | |||

| Before stent | 16 | 12 | |

| After stent | 3 | 13 | |

| Survival in days (mean ± SD) | 99.8 ± 97.3 | 100.5 ± 89.4 | |

Complications.

| Group A FCSEMS n = 21 | Group B PCSEMS n = 29 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complications | 7 | 15 | 0.634 |

| Early complications | 4 | 6 | 0.729 |

| Chest pain | 1 | 2 | |

| Bleeding | 0 | 0 | |

| Migration | 3 | 3 | |

| Obstruction caused by tumor | 0 | 0 | |

| Obstruction caused by food | 0 | 1 | |

| Late complications | 3 | 9 | 0.881 |

| Chest pain | 0 | 0 | |

| Bleeding | 0 | 1 | |

| Migration | 1 | 2 | |

| Obstruction caused by tumor | 0 | 5 | |

| Obstruction caused by food | 2 | 1 | |

| Migration (total) | 4 | 5 | 0.590 |

| Chest pain (total) | 1 | 2 | |

The cases of stent migration were managed through re-positioning (n = 3) or removal (n = 1) of the stent. In 2 cases, food was the cause of obstruction, and was extracted using a net.

The mean survival was 99.8 days (range: 3-322, 97.3 SD) after stent placement.

Group B (n = 29) (Table 1) was made up of 24 men and 5 women, with a mean age of 67.5 years (range: 43-92). Stent indication was dysphagia in 26 of those patients (89.6%) and dysphagia plus tracheoesophageal fistula in 3 patients (10.3%). Thirteen patients (44.8%) had grade 3 dysphagia and 16 patients (55.1%) had grade 4. Dysphagia duration before stent placement was a mean 4.3 months (± 3.57). Chemoradiotherapy was administered before stent placement in 12 patients (41.3%) and after stent placement in 13 (44.8%). The other 4 patients only had stent placement. Tumor was located in the distal third in 19 patients (65.5%), in the middle third in 9 patients (31%), and in the proximal third in one patient (3.4%). The tumor affected the esophagogastric junction in 16 (55.1%) of the patients. Technical success was achieved in 29 cases (100%) and clinical success in 26 (89.6%) (Table 2). Dysphagia after stent placement was grade 1 in 11 patients (37.9%), grade 2 in 15 patients (51.7%), and grade 3 in 3 patients (10.3%) (Table 2). A total of 15 patients (51.7%) presented with complications (Table 3). Six patients (20.6%) had early complications, of which 2 cases (6.8%) presented with chest pain, 3 cases (10.3%) with stent migration, and one case (3.4%) with obstruction caused by food. Nine patients (31%) presented with late complications, of which 5 (17.2%) were obstruction caused by the tumor, one (3.4%) was bleeding, 2 (6.8%) were migration, and one (3.4%) was obstruction caused by food. Of the complication total, there were 5 cases (17.2%) of stent migration. Of those patients, 3 cases (60%) corresponded to distal tumor affecting the esophagogastric junction and 2 (40%) corresponded to tumor at the middle third of the esophagus. All of those cases were managed through re-positioning of the stent.

Causes of obstruction in 5 cases were found to be tumor on an uncovered segment of the stent in the middle esophagus (n = 2) and in the distal esophagus (n = 3). They were managed through the placement of a new stent (n = 1) and argon plasma tumor ablation (n = 4). In the case of obstruction caused by food, treatment was its removal utilizing a net.

The patient that had bleeding presented with it 168 days after stent placement. The bleeding was secondary to an ulcer at the proximal end of the stent and was controlled through 1:10,000 adrenaline injection and hemoclip placement on a visible vessel.

In that group, survival after stent placement was a mean 100.5 days (range:10-410, 89.4 SD)

When the results of the two groups were compared, the success percentages for dysphagia relief were similar (90.4% for group A vs. 89.65% for group B), with no statistically significant difference between the groups (p = 0.924). There was also no difference with respect to early complications (19 vs. 20.6%, p = 0.729) or late complications (14.2 vs. 31%, p = 0.881) (Table 3). No cases of obstruction due to tumor growth were observed in relation to late complications in the FCSEMS group, compared with 5 cases (17.2%) in the PCSEMS group (p = 0.65). Similar results were found for the migration total analysis (19.04 vs. 17.2%, p = 0.590), for the effect of chemoradiotherapy on migration (p = 0.177), and for the effect of chemoradiotherapy on clinical success (p = 0.432). Finally, there was no statistical significance with respect to the analysis of the need for reintervention secondary to obstruction or stent migration (33.3% in group A vs. 42.8% in group B, p = 0.54).

Discussion and conclusionsThe placement of self-expandable metallic stents provides immediate dysphagia relief in 95% of patients and enables oral diet.3,4 In the majority of studies comparing covered esophageal stents with UCSEMSs, the covered esophageal stents are actually PCSEMSs. In their randomized multicenter study, Vakil et al. compared UCSEMSs versus PCSEMSs that had the same design. They found that although the two types of stent had similar success percentages in dysphagia relief and in cases of migration (12% with PCSEMS vs. 7% with UCSEMS, p = 0.43), the reintervention percentage was lower in the group with PCSEMS (0 vs. 27%, p = 0.002). In addition, the percentage of obstruction due to tumor ingrowth or to mucosal hyperplasia was lower in the PCSEMS group (3 vs. 30%, p = 0.005).1

In a similar retrospective study, Saranovic et al. found that recurrent dysphagia due to re-stricture was lower in the PCSEMS group, compared with the UCSEMS group (8 vs. 37%, p < 0.0001). In contrast, the use of a PCSEMS was associated with a higher migration percentage (10 vs. 0%, p = 0.03).5 Verschuur et al. also reported that tumor growth inside or outside of the stent occurred more frequently with the Ultraflex® PCSEMS (31%) than with the Niti-S® FCSEMS (24%).6 In our 2 groups, the success percentages for dysphagia relief were similar, with no statistically significant difference between them. In addition, even though a difference was found in the percentage of cases with obstruction due to tumor ingrowth, it was not statistically significant (0% for group A vs. 17.2% for group B, n = 5). Unlike the studies by Vakil et al. and Saranovic et al., we found no difference in the percentages of migration cases (19% for group A [n = 4] vs. 17.2% for group B [n = 5]). The difference those authors found was due to the fact that they compared covered stents with uncovered stents. In our study there was no difference in the cases with migration for 2 important reasons. First, because the 2 types of stents had a covering, and second, because the majority of the cases with migration were related to tumors that affected the esophagogastric junction (3/4 in group A and 3/5 in group B). In most of those cases, the distal end of the PCSEMs remained floating in the stomach, making it difficult to attach onto the tumor.

There is rapid dysphagia palliation and a reduction from grade 3 to grade 1 after the application of any type of stent.7 However, up to 50% of patients require reintervention due to dysphagia secondary to tumor growth or stent migration during long-term follow-up.8 In a study on 41 patients, permeability at 30, 90, and 180 days was 94%, 78%, and 67%, respectively.9 In our patients, the reintervention percentage was lower in the patients with FCSEMS (28.5% for group A [n = 6] vs. 44.8% for group B [n = 13]), although most of the reintervention cases in patients with both types of stents were related to migration or obstruction due to tumor or food.

Migration is more frequent when the stent is placed through the esophagogastric junction, when the patient receives chemotherapy or radiotherapy, or when fully covered stents are used.10 In the patients we studied, there was no apparent effect from chemoradiotherapy on the possibility of migration, but different unknown factors, such as total chemoradiotherapy dose and tumor length and characteristics could influence that result.

Studies on PCSEMS, such as Ultraflex®, Evolution®, and WallFlex®, have shown migration percentages of 4 to 23, 5, and 6%, respectively,6,11–16 whereas ALIMAXX-E® (Alveolus, Charlotte, NC, USA) and SX-ELLA® have had migration percentages of 36 and 14 to 20%, respectively.17,18 Improvement of 3 to 1 on the dysphagia scale was reported for the SX-ELLA® stent, but bleeding and fistula formation in 25 and 6% of patients, respectively, was also described.17 The study suggested that the complications could be secondary to friction caused by the anti-migration ring. In the patients we evaluated in group A (SX-ELLA®), the migration percentage was similar and there were no cases of bleeding or fistula.

A study on 3 types of stent (Ultraflex®, Flamingo® [Boston Scientific], and Gianturco® [Cook, Ireland]) showed that large-diameter stents reduced the risk for dysphagia secondary to stent migration, tumor growth, or obstruction due to food (OR: 0.35; 95% CI: 0.2-0.7). The negative aspect was an increase in the complications of bleeding, perforation, fistula, and fever, especially for the Gianturco® Z-stent (OR: 5.0, 95% CI: 1.3-19.1).16

Food impaction inside the stent causes dysphagia recurrence and its frequency depends on the type of stent used. That complication was seen in two studies in 7 and 5% of the patients that received Evolution® and WallFlex® stents, respectively.19,20 In our case series, that type of recurrence was observed in 9.5% (n = 2) of the group A patients (SX-ELLA®) and in 6.8% (n = 2) of the group B patients (Ultraflex®).

The authors of a meta-analysis concluded that there was no difference between covered metallic stents in relation to the incidence of adverse events.21 We also found no difference in the overall complication percentages between the two stent groups studied (33% for group A [n = 7] vs. 51.7% for group B [n = 15]; p = 0.634).

The main advantage of the FCSEMS is that it can be extracted when necessary. However, that rarely occurs when the stent is used as a palliative measure. That characteristic also allows its repositioning when required, as was performed in 3 of the group A patients.

We are aware of the limitations inherent in the retrospective design of our study and the possibility of multiple factors of bias. Despite those aspects, our results were not different from those of previous studies and show that FCSEMSs had the same results as PCSEMSs in the palliative treatment of esophageal cancer. There were no cases of late obstruction due to tumor ingrowth with the FCPSEMSs, which could be an argument in favor of their use, but that finding requires further study.

In conclusion, there were no significant differences between FCSEMSs and PCSEMSs with respect to technical success, clinical success, permeability, or complications in patients with unresectable esophageal cancer.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Financial disclosureNo financial support was received in relation to this study.

Conflict of interestDr. Angélica Hernández Guerrero and Dr. Mauro Eduardo Ramírez Solís are Speakers for Boston Scientific. The remaining authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Alonso Lárraga JO, Flores Carmona DY, Hernández Guerrero A, Ramírez Solís ME, de la Mora Levy JG, Sánchez del Monte JC. Prótesis totalmente cubiertas versus parcialmente cubiertas para el tratamiento paliativo del cáncer de esófago: ¿hay alguna diferencia? Revista de Gastroenterología de México. 2018;83:228–233.