Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is a rare condition, but nevertheless, it causes 40-50% of the cases of acute liver failure.1,2 There are 3 patterns of injury: hepatocellular, cholestatic, and mixed, and the cholestatic pattern accounts for 20-40% of the cases.3,4 Its manifestations range from biochemical alterations in the absence of symptoms to acute liver failure and chronic liver damage. It is a diagnosis of exclusion, based on circumstantial evidence. In the majority of cases, the patient's symptoms improve with the removal of the medication responsible for the injury.5

We present herein the case of a 38-year-old man with a history of alcoholism of 15-year progression, drinking 21.6g of alcohol daily. The date of his last alcohol consumption (1 liter of fermented alcohol), without reaching a drunken state, was one week before the onset of clinical symptoms. He had been applying one vial a week of intramuscular anabolic steroids, containing 250mg of testosterone, 100mg of nandrolone, and 50mg of stanozolol, for 31 days.

After one day of not injecting those drugs, the patient presented with clinical symptoms characterized by jaundice, generalized pruritus, and nausea. Upon his admission to the emergency unit, the patient's vital signs were within normal parameters. Physical examination revealed jaundice, no asterixis, and abdominal pain at the level of the right hypochondrium, described as 5/10 on the Visual Analogue Scale. Laboratory work-up results showed: total bilirubin 33.87mg/dl (0.1-1.0), direct bilirubin 26.41mg/dl (0.1-0.25), ALT 49 IU/l (10-40), AST 65 IU/l (15-41), GGT 60 IU/l (9-40) and alkaline phosphatase 207 IU/l (38-126). A hepatobiliary ultrasound study was carried out that demonstrated no evidence of bile duct dilation and identified vascular permeability and normal liver morphology. Magnetic cholangioresonance revealed no alterations. Special laboratory tests were ordered as part of the approach to cholestasis, and the results were negative for hepatotropic virus serology (HAV, HBV, HCV, and HEV) and for cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus. The serologic profile of autoimmune hepatopathies reported negative ANAs (IIF), antimitochondrial antibodies, anti-smooth muscle antibodies, and anti-LKM1 antibodies.

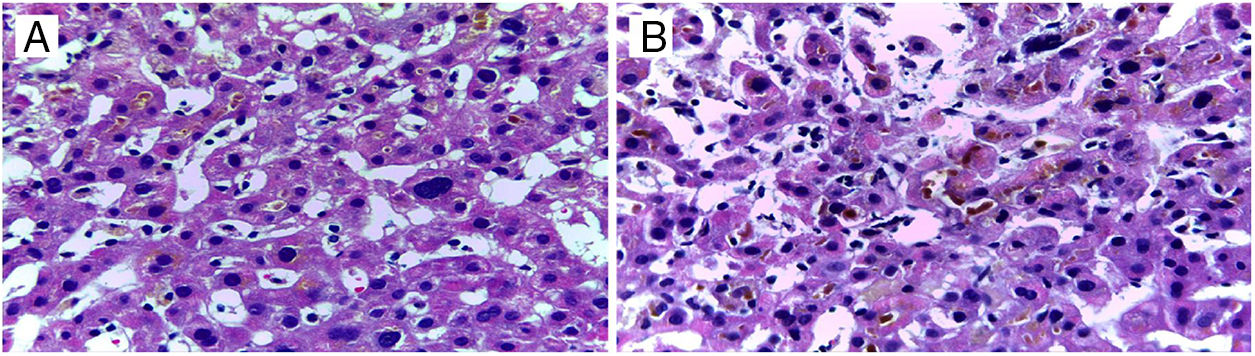

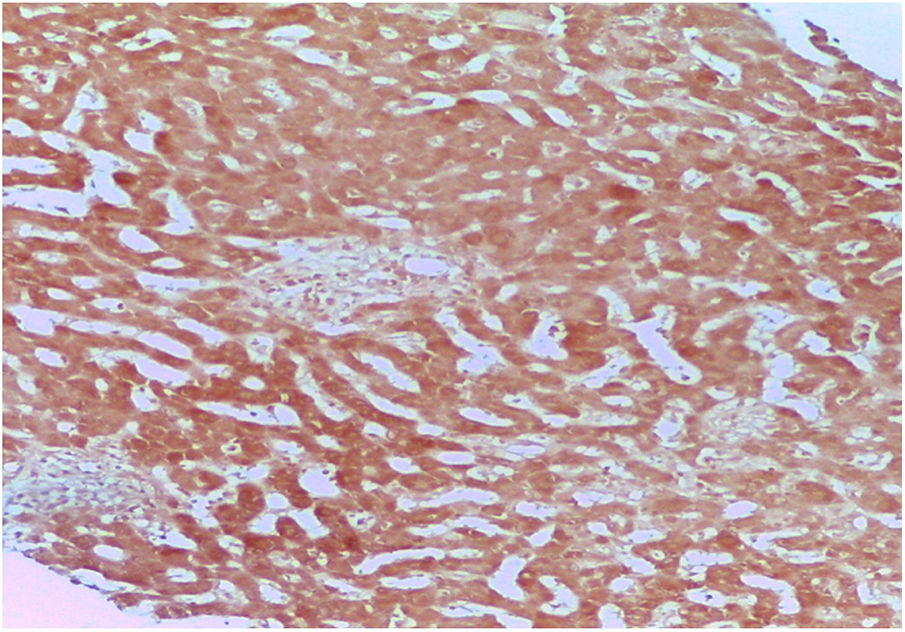

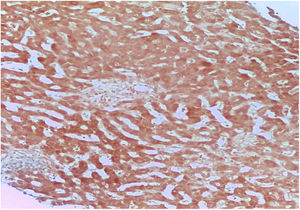

DILI secondary to the application of anabolic steroids was suspected, and so an R value of 0.27 was calculated, indicating a pattern of cholestatic injury. A percutaneous biopsy of liver tissue was taken and accentuated intracytoplasmic and canalicular cholestasis predominating in perivenular zones 2 and 3 (Figs. 1 and 2) was reported. A score of 9 was calculated using the Council for International Organizations of Medical Scientists/Roussel Uclaf Assessment Method (CIOMS/RUCAM) scale, indicating definitive DILI.

The patient was initially managed with 60mg of methylprednisolone every 24h and then with a reduced dose of prednisone, 500mg of S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe) every 12h and 15mg/kg/day of ursodeoxycholic acid in 3 takes during 5 days of hospital stay, with adequate clinical progression. After his release from the hospital, the patient's progression was favorable, and his liver function tests became normal 4 months after anabolic steroid suspension.

Even though there is little epidemiologic information on the toxic effect of drugs on the liver, it is known that its incidence is increasing in parallel with the introduction of new medications, the increase in life expectancy, and polypharmacy. Accurate diagnosis is complicated and notification of adverse reactions to drugs by healthcare professionals is limited.1–3 The problem of under-notification with respect to anabolic steroids is even greater because they are substances that are often obtained and consumed with no medical prescription.

Currently there are very few accepted indications for either oral or parenteral anabolic steroid use. Hepatotoxicity induced by anabolic steroids is dose-dependent and predictable. Its most frequent presentation is cholestatic hepatitis, and other types of injury associated with high doses of the drugs are: bland or “pure” cholestasis, acute cholestatic hepatitis, acute hepatocellular injury, and hepatic tumors.4

In the case presented herein, the patient had severe jaundice with a minimal elevation of liver enzymes, consistent with bland cholestasis. There was a clear temporal relation between the beginning/end of treatment and the appearance/disappearance of symptoms, respectively. In addition, other causes of liver injury were ruled out. With all the above and a score of 9 on the CIOMS/RUCAM hepatotoxicity evaluation scale,5–7 it was concluded that the patient had highly probable or definitive hepatotoxicity due to anabolic steroid use. The US National Institutes of Health also has a website (www.livertox.nih.gov) that describes cases of hepatotoxicity and the mechanism of the liver injury the drugs can cause.

Our patient's liver biopsy showed a canalicular pattern consistent with his clinical and biochemical characteristics and he had adequate progression after the suspension of the anabolic steroids.

As occurred in our patient, SAMe use has shown a favorable response when combined with ursodeoxycholic acid. Different meta-analyses have determined the efficacy of SAMe in reducing pruritus and the serum bilirubin values associated with cholestasis, compared with placebo.8

The long-term prognosis for DILI generally depends on the initial clinical and biochemical presentation in the patient.9 The present case is of interest due to the approach carried out to reach the diagnosis of DILI, its adequate treatment, and the good progression of the patient, despite his initially high total bilirubin levels.

Ethical disclosuresThe authors declare that the present article contains no personal information that could identify the patient and meets the current norms of and is approved by the institutional research and ethics committee.

Financial disclosureNo financial support was received in relation to this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

The authors wish to thank the personnel at the Departments of Internal Medicine and Pathologic Anatomy of the Hospital General “Dr. Manuel Gea González”, Mexico City, Mexico.

Please cite this article as: Díaz-García JD, Córdova-Gallardo J, Torres-Viloria A, Estrada-Hernández R, Torre-Delgadillo A. Lesión hepática inducida por fármacos secundaria al uso de esteroides anabólicos. Revista de Gastroenterología de México. 2020;85:92–94.