The management of walled-off pancreatic necrosis is currently a challenge. Innovative, minimally invasive techniques have been developed in recent years and have shown excellent results, compared with conventional surgical techniques. Some such minimally invasive techniques are image-guided percutaneous pigtail catheter drainage and endoscopic transgastric drainage, with or without the use of endoscopic ultrasound.1–3 However, when there is therapeutic failure or contraindication with the use of those options, walled-off pancreatic necrosis management tends to lean toward laparoscopy and/or laparotomy, which are more invasive and produce important morbidity and mortality. A retroperitoneal and transabdominal percutaneous-endoscopic approach has begun to be performed, with a satisfactory success rate, as a new therapeutic option, before resorting to the more aggressive procedures.4–7 A case is presented herein to describe a therapeutic approach with percutaneous-endoscopic transabdominal drainage, utilizing an esophageal fully covered self-expanding metal stent for accessing and debriding the infected pancreatic necrosis.

A 53-year-old woman presented with colicky epigastric pain of 7-hour progression, accompanied by emesis, and radiating to the lumbar region. Her amylase level was 3-times higher than its usual value (754 U/l). Upon admission, the patient had a Ranson's criteria score of 2, a mild Atlanta classification, and a double-contrast tomography scan identified changes consistent with acute pancreatitis with a Balthazar E severity score. It also revealed a focus of multiseptated, superinfected, necrotizing pancreatitis, compromising more than 50% of the pancreatic parenchyma. In addition, possible communication of the pancreatic duct with the collection, significant edema around the entire pancreas, and peripancreatic fluid were found, for which initial clinical and endoscopic management were carried out. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography was indicated due to the high risk for gallstones in the bile duct that presented at evaluation (total bilirubin 4.8mg/dl, direct bilirubin 4.2mg/dl, AST 74mg/dl, ALT 56mg/dl) and the possible communication of the pancreatic duct with the infected necrosis previously observed in the tomography scan.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography was carried out. After biliary and pancreatic sphincterotomy, both the bile and pancreatic ducts were cannulated. Due to the high suspicion of a main pancreatic duct fistula at the level of the body of the pancreas, a 5 Fr plastic pancreatic stent was inserted, after which extrusion of purulent material into the duodenum was observed. Bile duct stone extraction was also performed utilizing a Dormia basket.

Upon evaluation, the patient had been hospitalized for a longer period of time, with the recent in-hospital diagnosis of diabetes mellitus that required insulin therapy. Her clinical picture deteriorated, and she presented with an active systemic inflammatory response, treated with broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy indicated by the Infectious Diseases Service. The decision was made by the Interventional Radiology Service to perform percutaneous drainage of the lesions described above, providing only partial improvement. The patient had persistent drainage of large quantities of bloody-purulent material (1,000ml/24h), and so a Medical Meeting of the Digestive Surgery, Gastroenterology, and Interventional Radiology services was held. There is evidence in the medical literature that echoendoscopy is the ideal approach in cases such as that of our patient, but our hospital had neither the resources nor the institutional experience for its safe performance. Therefore, the percutaneous-endoscopic approach was decided upon, which would enable necrotic tissue debridement as an alternative to conventional management.

Procedure- 1.

With the patient under general anesthesia, the percutaneous catheter, previously inserted by the interventional radiologist, was filled with a contrast medium, and under fluoroscopic vision, a fistulous tract between the skin and the infected pancreatic necrosis was shown.

- 2.

A 0.035” x 150cm hydrophilic guidewire was advanced over the catheter.

- 3.

Sequential pneumatic balloon dilation of the wall was carried out at 10, 14, 16, and 20 units of atmospheric pressure (ATM).

- 4.

Under fluoroscopic vision and over the hydrophilic guidewire, an esophageal stent was inserted, with its distal cup situated in the infected necrotic cavity and its proximal cup in the skin of the left flank.

- 5.

The esophageal stent within the tract corresponding to the abdominal wall was dilated using an 18mm x 40mm Atlas high pressure balloon that was insufflated up to 28 ATM, enabling the endoscope to pass through the opening of the esophageal stent.

- 6.

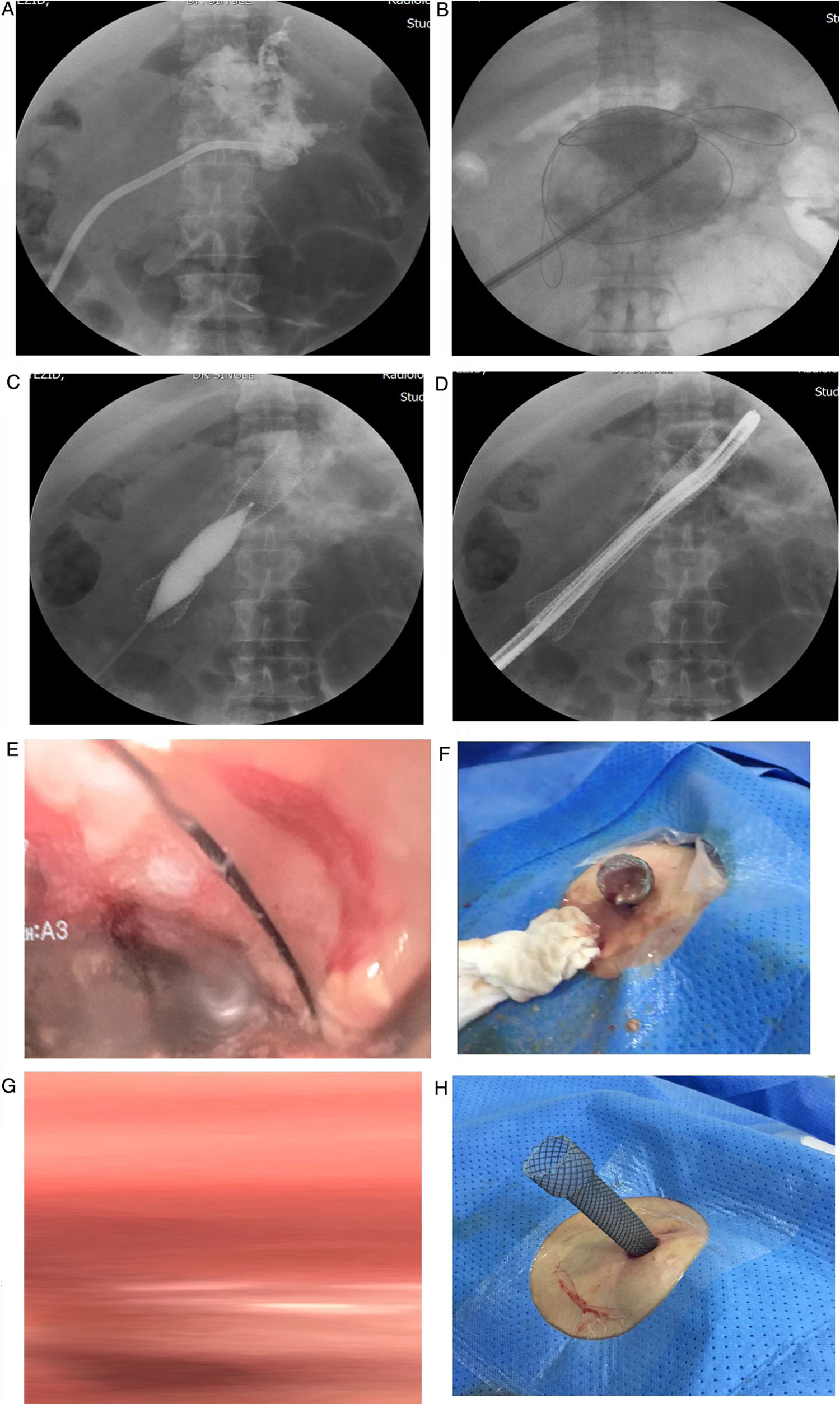

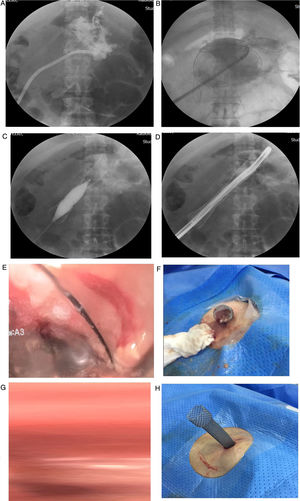

A 9mm Olympus 180 frontal endoscope was passed through the esophageal stent to examine the cavity, debride the necrotic tissue with a Dormia basket, and perform lavages with saline solution (fig. 1A-H). The proximal portion of the stent was left exposed at the skin between lavages because the endoscopic and imaging findings suggested an unclean cavity. Lavages were performed every other day, after local asepsis, at the patient's bedside, for approximately one month. The patient had satisfactory clinical and radiologic progression at follow-up (figs. 2 and 3).

Figure 2.Fluoroscopic and endoscopic images during the procedure. A) The necrotized pancreatic cavity is enhanced with contrast medium. B) The esophageal fully covered self-expanding metal stent is inserted over the hydrophilic guidewire. C) Hydrostatic balloon dilation in the body of the esophageal stent is performed to enable the passage of the endoscope into the necrotized pancreatic cavity. D) Advancement of the endoscope into the necrotized pancreatic cavity. E) Endoscopic view of the area of necrosis. F) Extrusion of necrotic material after the endoscopic lavage. G) Image after the first endoscopic lavage. H) The exposed stent in place for further lavages.

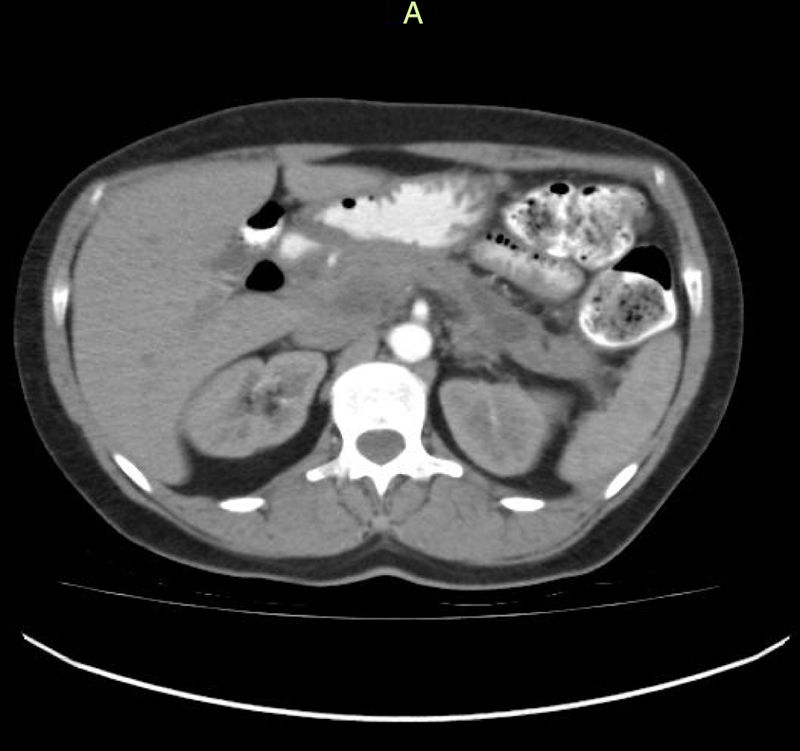

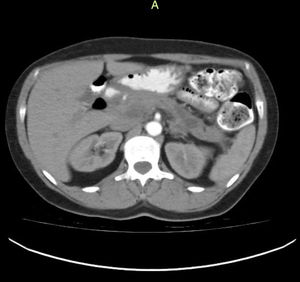

(0.37MB).Figure 3.Control contrast-enhanced abdominal tomography scan, 3 months after the event, showing a decrease in edema and inflammatory pancreatic involvement, as well as a single residual collection with no radiologic signs of associated superinfection. The patient was completely asymptomatic when the scan was taken.

(0.05MB).

Superinfected walled-off necrosis has traditionally been managed through exploratory laparotomy, open abdomen, successive lavages, and necrosectomy.8,9 The combined management with catheters and drains enables continuous lavage and necrotic tissue debridement with good success rates.7–10 Nevertheless, those procedures have high rates of morbidity and mortality, producing complications such as bleeding, evisceration, and intestinal fistulas, among others.5–7 In recent years, the development of minimally invasive techniques has made a single surgical concept possible, with less morbidity. The use of percutaneous drains carried out by an interventional radiologist is a method that has achieved patient improvement, partly associated with the fact that it is minimally invasive. It has the disadvantage of not being able to remove the abundant necrotic tissue in an extensive walled-off pancreatic necrosis. Therefore, management through percutaneous-endoscopic transabdominal drainage is an alternative that can manage complicated collections, maintaining a range of local action, effectively providing the patient with recovery and symptom improvement.7

That procedure was shown to be an effective method for resolving infected walled-off pancreatic necrosis and we propose it as a safe and minimally invasive intervention, performed at the patient's bedside, with only mild pain when performing successive lavages. In addition, it is a low-cost procedure, compared with other more aggressive methods.

Ethical considerationsThe authors declare that the present work followed international ethics principles. Statements of informed consent were obtained from the patient for each procedure and for the later academic publication of the case. In addition, the work was authorized by the corresponding hospital committee for the performance of the abovementioned procedures, following the national regulations (Law 8430 from the year 1993). The patient cannot be identified in any of the images or descriptions, completely maintaining her anonymity.

Financial disclosureNo financial support was received in relation to the present article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Mendoza J, Tovar G, Galvis M, Mendoza M, Lozano C. Drenaje percutáneo endoscópico transabdominal en la necrosis pancreática encapsulada infectada: reporte de caso. Revista de Gastroenterología de México. 2020;85:94–97.