Ulcerative colitis (UC) is considered an idiopathic disease of the large bowel that consists of chronic mucosal inflammation due to a complex interaction between genetic predisposition and environmental factors. Worldwide incidence is reported to have plateaued in North America (19.2 per 100,000 person-years) and Europe (24.3 per 100,000 person-years), whereas low incidence regions, specifically in developing countries, appear to have experienced an increase in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) that is most likely due to industrialization.1 Epidemiologic data on UC are scarce in those countries, as they are in Mexico. In a recently published nationwide cohort study, encompassing more than 15 years (2000-2017), incidence was reported at 0.16 per 100,000 person-years and prevalence at 1.45 per 100,000 person-years for UC in Mexico, revealing a 5.3-fold increase.2 The extent and clinical course of the disease can vary, ranging from rectal involvement to pancolitis in a continuous manner, and the disease is characterized by a relapsing and remitting course. The phenotype at diagnosis in patients with UC is generally split equally between proctitis, left-sided disease, and pancolitis. Both IBD subtypes, namely UC and Crohn’s disease (CD), are chronic diseases consisting of chronic inflammation with subsequent constant tissue repair. CD presents with transmural disease with activation of mesenchymal cells and a subsequent stricturing disease course, whereas fibrosis and scar formation in long-standing UC is usually limited to the mucosa, including pseudopolyposis and bridging fibrosis.4 An increased risk of colorectal cancer has been recognized for UC, in particular, with a cumulative incidence of 2% in 10 years, 8% in 20 years, and 18% in 30 years.5 Those data highlight why neoplasia should be the primary suspicion when a colonic stricture is diagnosed. Nevertheless, in their original articles dating back to 1964, Edwards and Truelove reported benign strictures in UC patients in 6.3% of cases.6 The authors of a large case series on 1156 patients seen at the Mount Sinai Hospital between 1959 and 1983, found benign strictures in 42 cases (3.6%) that were mostly located in the left colon (68% in the rectum).7 More recently, in a Portuguese IBD study, the authors identified a prevalence of benign colonic strictures of 3%.8

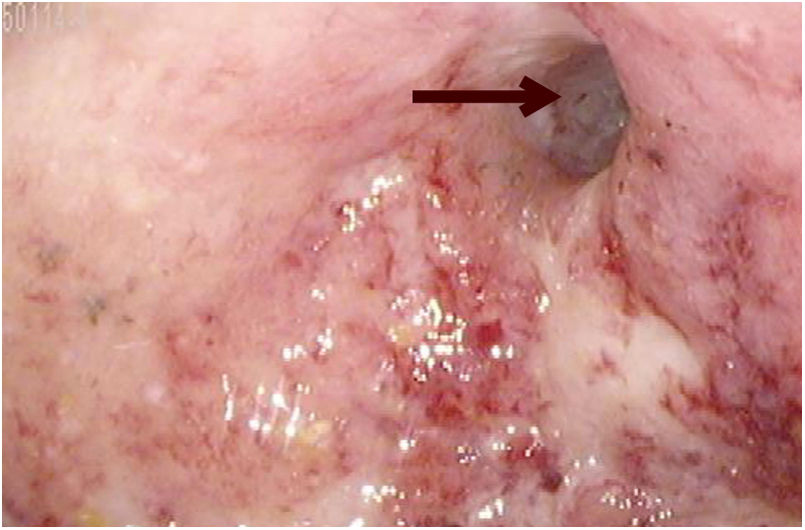

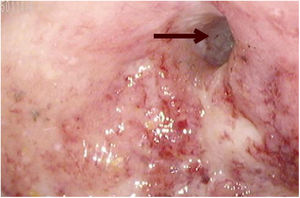

We present herein the case of a 28-year-old female patient with a history of steroid-dependent pancolitis and poor adherence to medical treatment with mesalazine and azathioprine. Her medical history included multiple UC flares, first diagnosed when she was 26 years old, that required several courses of corticosteroids. Her response to thiopurines was suboptimal, albeit mainly due to noncompliance. An episode of remission was never documented. Clinically, the patient continued to present with > 4 bowel movements per day, as well as hematochezia, requiring blood transfusions on several occasions. Biologic therapy was considered but before it was begun, a follow-up colonoscopy identified a stricture in the descending colon that prevented the passage of the colonoscope (Fig. 1), complicating the disease course. CT enterography revealed a colorectal narrowing with loss of transverse folds and circumferential mild diffuse colonic wall thickening, including the rectum, descending colon, and transverse colon, with mesocolic fat stranding and engorged vessels. Strictures were identified in the transverse and descending colon, measuring 6 cm and 2.6 cm in length, respectively. A total proctocolectomy with end-ileostomy was performed, and the two previously described strictures were macroscopically observed (Fig. 2). Upon histopathologic examination, a predominantly plasmocytic infiltrate with neutrophils in the crypts was observed. The patient’s postoperative progression was favorable. She currently empties her ileostomy bag 3-4 times per day, tolerates a normal diet, and has had adequate weight gain.

Long-standing UC that is progressive in nature may present with the complication of malignancy in up to 60% of patients.9 Though uncommon, benign strictures have been described to develop in up to 6.3% of UC cases.6 Due to the difficulty of ruling out malignancy, those cases are referred for surgical evaluation. Stricture pathogenesis in CD includes transmural inflammation that incites mesenchymal cell proliferation in the muscle layer. In contrast, the mechanism in UC is most likely caused by thickening of the muscularis mucosae induced by b-FGF-positive inflammatory neutrophils.10 Currently, the focus of treatment in patients with IBD has incorporated a “treat to target” approach, thereby shifting the emphasis onto endoscopic and histologic targets over clinical or symptomatic ones. Biologic agents have played a pivotal role in preventing long-term complications.3 Previously, the mean duration from disease onset to stricture formation was reported to be 15.6 ± 8.6 years, and longer disease duration was associated with malignancy.7,10 Our patient had severe disease progression, with benign stricture formation at only two years from disease onset. Due to the current lack of disease markers for stricturing UC, the present case underlines the importance of early recognition and aggressive treatment, including patient information and education that, in turn, promotes treatment adherence.

All authors wrote, edited, and approved the final version of this article.

Verbal informed consent from the patient was obtained for the case report. Written informed consent was not obtained since the present manuscript does not include personal information that could identify the patient.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Scharrer-Cabello SI, Baeza-Zapata AA, Herrera-Quiñones G, Luna-Limón CG, Benavides-Salgado DE. Colitis ulcerosa con estenosis: un caso de progresión rápida de la enfermedad. Revista de Gastroenterología de México. 2020;85:491–493.