Intestinal tuberculosis accounts for 2% of the cases of tuberculosis worldwide. It can present completely asymptomatically, or with few symptoms,1 and mimic other abdominal diseases,2–3 making its diagnosis a challenge. Its misdiagnosis reaches rates of up to 50–70%, even in countries where tuberculosis is endemic.

A 67-year-old man with an unremarkable past medical history and no previous contact with individuals presenting with tuberculosis was included in a population screening program for colorectal cancer. The fecal occult blood test was positive, and his only symptom was occasional episodes of colicky abdominal pain.

Following the evaluation protocol, diagnostic colonoscopy was performed, in which an ulcerated stricture was revealed at the level of the hepatic flexure, preventing the passage of the endoscope (Fig. 1), and was suggestive of a neoformation. Biopsy specimens were taken, and tattooing was applied, in a distal direction. Only uncomplicated diverticula were observed in the rest of the examination.

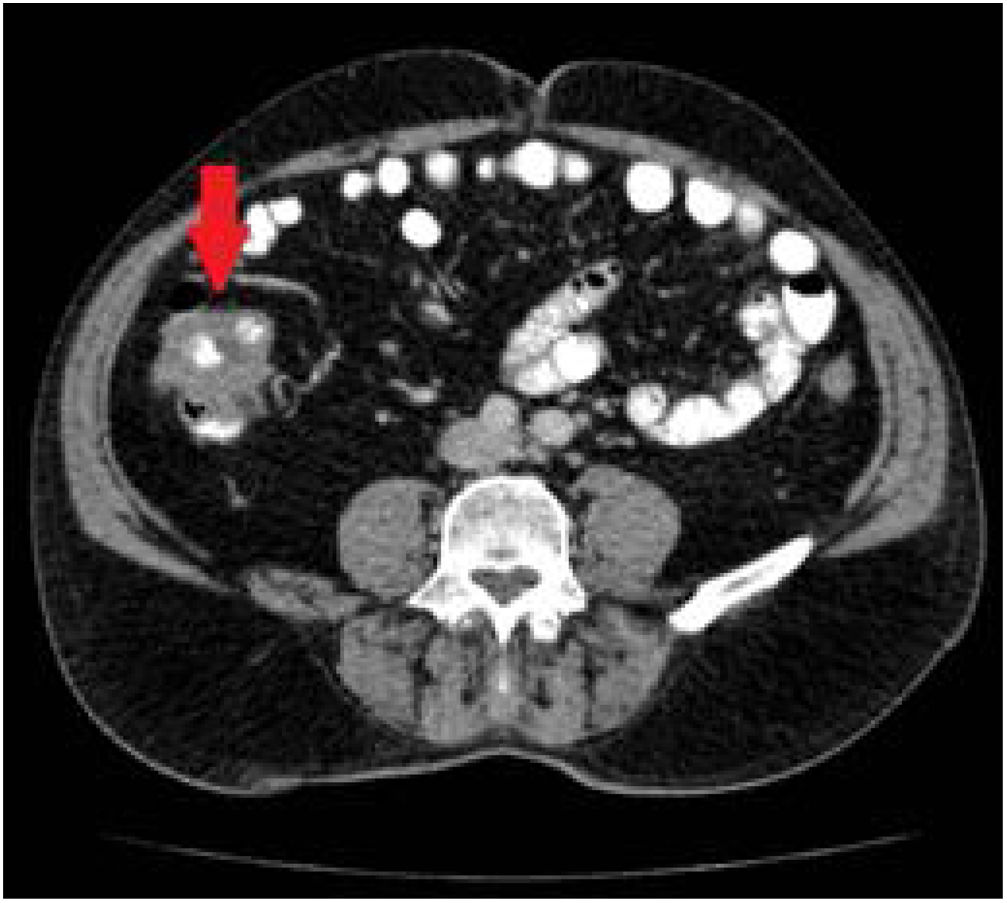

Given those findings, a chest and abdominal CT scan was carried out that described a thickening in an approximately 8 cm segment of the ascending colon, toward the hepatic flexure, with probable involvement of the ileocecal valve, consistent with a primary tumor with no adenopathies, distant disease, or signs of bowel obstruction (Fig. 2).

The anatomopathologic study of the endoscopic biopsy described necrotizing granulomatous inflammation, with no signs of malignancy. Nevertheless, because the endoscopic features and radiologic images raised the suspicion of a primary tumor, the patient underwent a laparoscopic right hemicolectomy, with extracorporeal anastomosis. His postoperative progression was good.

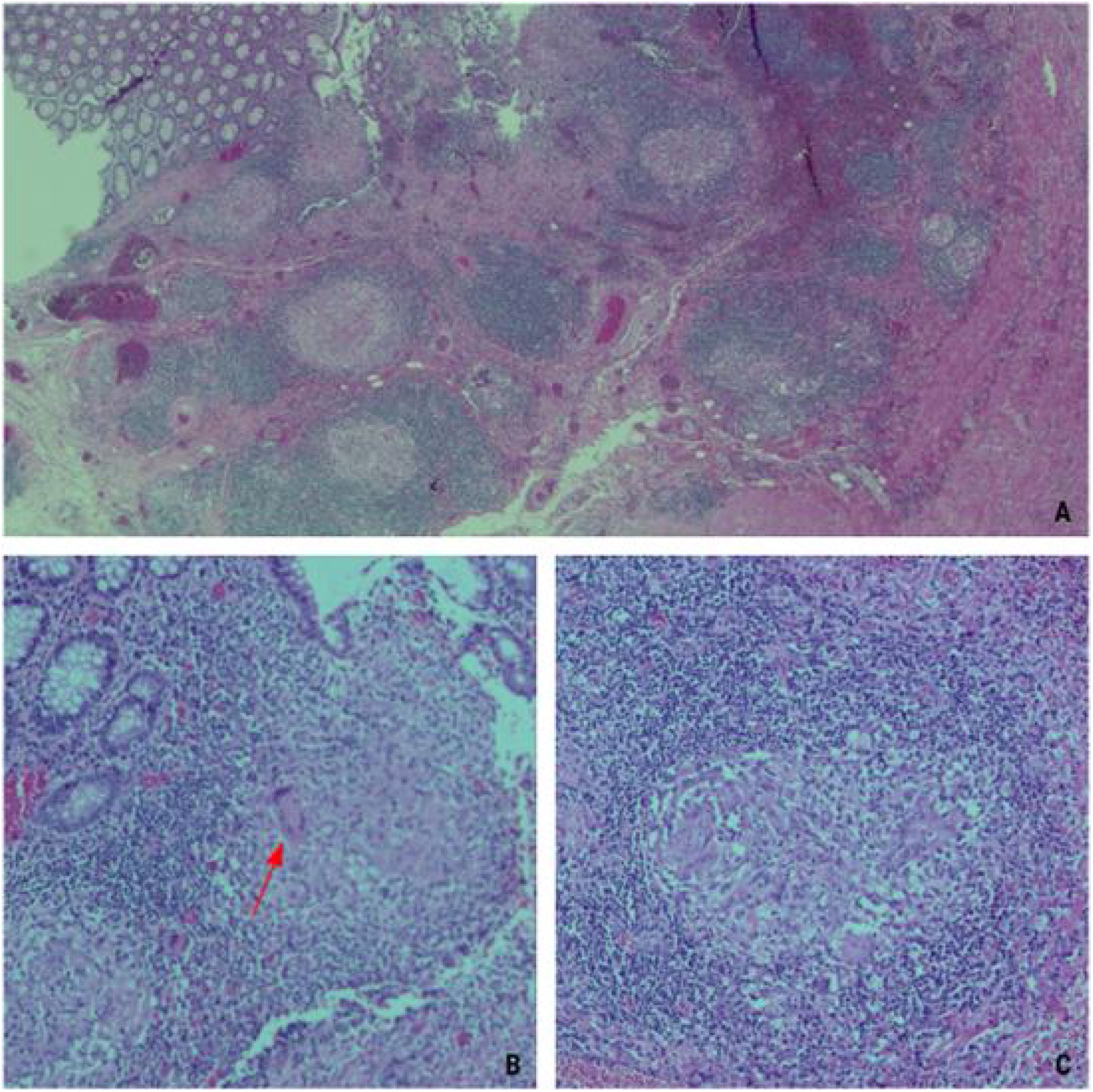

The pathologic study of the surgical specimen also described necrotizing granulomatous inflammation (Fig. 3), with no signs of malignancy. The differential diagnosis was between Crohn’s disease, with a stricturing pattern, and intestinal tuberculosis. Surgical specimen PCR testing for Mycobacterium tuberculosis was positive, confirming the relation of the endoscopic and radiologic findings to intestinal tuberculosis, and antituberculosis treatment was started.

Microscopic images of several surgical specimen sections. (A) Image showing the ulcerated mucosa and the presence of granulomas in the lamina propria of the mucosa (×2.5 magnification). (B) Image showing the presence of a Langhans giant cell (red arrow), with its characteristic multiple nuclei arranged on the periphery (×10 magnification). (C). Image of a tuberculous granuloma that distinguishes the lymphocytic collarette surrounding epithelioid cells (×20 magnification).

Intestinal tuberculosis is a form of abdominal involvement due to Mycobacterium tuberculosis, with a much lower prevalence than the customary manifestation of the infection in the lung, but its elevated morbidity and mortality could be associated with its challenging diagnosis. The disease can be completely asymptomatic,4 as in the case presented herein, or may present with only a few symptoms, such as abdominal pain, weight loss, or fever,5–8 thus being indistinguishable from other abdominal conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease or those with a malignant etiology. Currently, the combination of clinical presentation, endoscopy, radiologic imaging, and pathologic findings is key for making its diagnosis.3,5

Intestinal tuberculosis predominantly affects the ileocecal region (64%),5,9,10 with isolated involvement of the colon described in approximately 10.8% of cases. Incidence is greater in immunocompromised patients and the most affected area tends to be the cecum,8,9 because of its contiguity to the ileocecal region.

During colonoscopy, the most frequent finding is that of irregular, nodular, erythematous, and edematous mucosa, with areas of ulceration,5,7,9 which is different from that observed in Crohn’s disease, in which the mucosa surrounding the ulcers usually appears normal.

Radiologically, abdominal CT findings of intestinal tuberculosis include wall thickening of a segment of the intestine, abdominal adenopathies with central necrosis, intra-abdominal collections, or peritoneal inflammation. When there is colorectal involvement, the most frequent findings are strictures, signs of colitis, or polypoid lesions. In such cases, amebic, ischemic, or pseudomembranous colitis, as well as malignant disease, make up the differential diagnosis of colorectal tuberculous involvement. Therefore, diagnosis must be based on a high degree of suspicion and demonstrated by the presence of caseating granulomas in the endoscopic intestinal biopsies,8,9 which is an aspect that differentiates the diagnosis from that of Crohn’s disease, together with a positive smear or culture for acid-resistant bacilli.7,8 However, in some cases, the clinical and endoscopic response to antituberculosis treatment is still needed to make the diagnosis.5,7

As mentioned above, the treatment of choice is antituberculosis therapy for at least 6 months, including isoniazid, rifampicin, and pyrazinamide, the first 2 months of the therapeutic regimen, followed by 4 months of isoniazid and rifampicin. The response to medical treatment tends to be good, reserving surgery for nonresponders or patients with associated complications. Medical management results in significant symptom resolution in the majority of cases, including those of stricture.6–9 Thus, if patients are asymptomatic after medical treatment of colonic lesions, follow-up colonoscopy is not required.

In summary, intestinal tuberculosis is a disease that is difficult to diagnosis, its clinical presentation is nonspecific, and it can be confused with other entities, such as tumors or Crohn’s disease. The combination of endoscopic and histologic studies is essential for making the correct diagnosis and starting early drug treatment, thus preventing possible complications and providing cure in the majority of cases.

Financial disclosureNo financial support was received in relation to this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical considerationsNo experiments were conducted on humans for the present study and the authors followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data. Authorization by the institutional ethics committee was not required, given that patient confidentiality and anonymity were preserved at all times. The authors declare that this article contains no personal information that could identify the patient. Informed consent for the surgical intervention was requested of the patient, and included a section stating the possibility of using images and clinical data for scientific purposes.

Please cite this article as: Suárez-Noya A, González-Bernardo O, Riera-Velasco JR, Suárez A. Tuberculosis intestinal como simuladora de una neoplasia de colon. Rev Gastroenterol Méx. 2023;88:183–186.