Gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE), called “watermelon stomach” is rare and has been reported as a cause of non-variceal gastrointestinal bleeding in 4% of adults. Only isolated cases have been reported in children, but its opportune recognition and treatment are important, given that it can manifest as an acute and life-threatening bleeding episode.1,2 It has been associated with other pathologies, such as autoimmune diseases, chronic renal insufficiency, and liver cirrhosis, as well as with patients undergoing treatment with immunosuppressants.1–3 Its endoscopic image is described as linear, erythematous spots that irradiate from the pylorus to the antrum. Sometimes it has the appearance of erosive gastritis and it can also be located in other areas, such as the cardia, small bowel, and rectum, hence its suggested name of gastric vascular ectasia (GVE).2,4,5 We present herein 3 pediatric cases of endoscopically diagnosed GVE treated with argon plasma electrocoagulation (APE).

Case 1: A 15-month-old boy diagnosed with Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome presented with gastroesophageal reflux disease that responded poorly to treatment. Occult bleeding with anemia with Hb 10.5g/dl was detected. Gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed an image consistent with GVE in the corpus and fundus and APE was performed. The patient had asymptomatic progression with Hb of 12.5g/dl.

Case 2: A girl, aged 4 years 6 months, presented with acute infectious diarrhea prior to an episode of melena and had a low Hb level of 6.7g/dl. Endoscopy revealed an image of GVE in the fundus and APE was performed. In the control endoscopy at 4 weeks, a 2nd APE session was performed on minimal vascular lesions with no further gastrointestinal bleeding and a control Hb of 12.5g/dl.

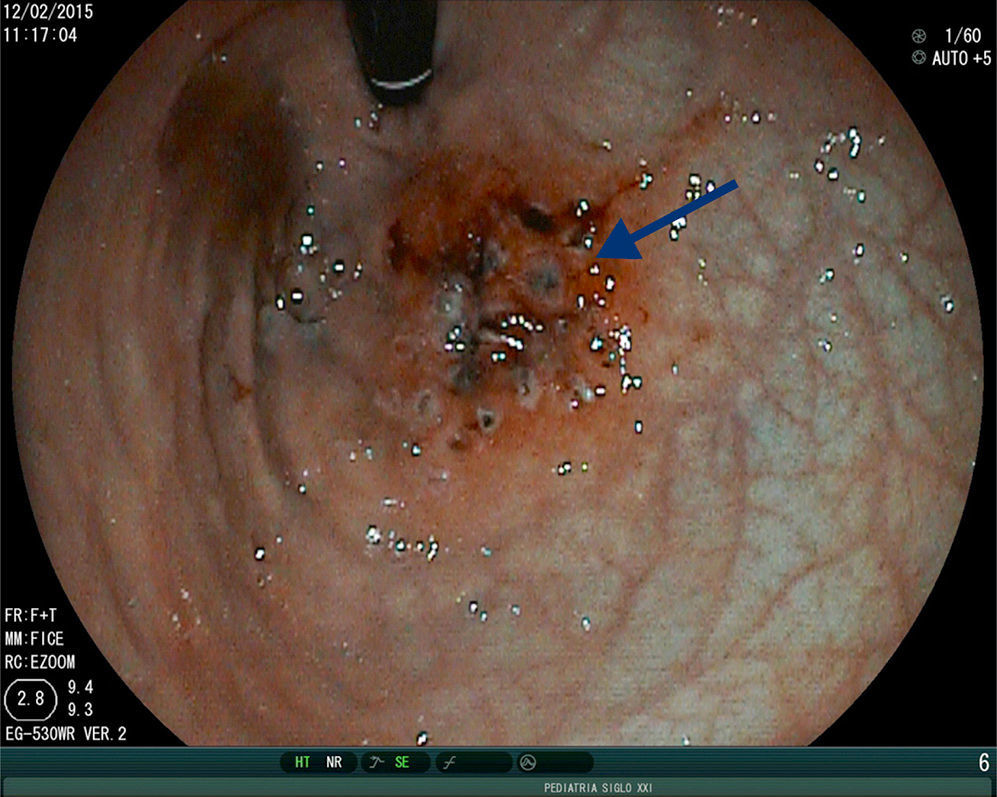

Case 3: A 9-year-old girl presented with acquired aplastic anemia, hematamesis, and a drop in the Hb level to 3g/dl. Endoscopy revealed “watermelon stomach” lesions in the corpus and fundus (Fig. 1). APE was applied and the patient progressed with no further bleeding. The control endoscopy at 4 weeks showed no change in the vascular lesions and a second APE session was applied. Two months later, the patient presented with a new episode of hematemesis due to GVE in the fundus and corpus. A third APE session was applied, controlling the acute gastrointestinal bleeding. One month later, the patient died due to intracranial hemorrhage.

The histopathology report in cases 1 and 2 stated follicular gastritis of the gastric fundus.

GVE can present as upper gastrointestinal bleeding, occult bleeding with anemia, or as abdominal pain. In our cases, gastrointestinal bleeding and anemia were the manifestations of GVE that were corrected following treatment with APE (Fig. 2) in cases 1 and 2. In case 3, both episodes of active bleeding were able to be contained through APE. We found an association with autoimmune diseases and with immunosuppressant treatment, concurring with reports in the literature.1,4,6 Treatment in adults for GAVE consists of endoscopic management with APE, laser photoablation, nitrous oxide cryotherapy, and coagulation with hemospray. APE is the most widely used technique due to its availability and its generally reversible complications, such as distension due to gas, emphysema, and gastrointestinal pneumatosis, unlike the complications of perforation or ulcers that can arise with other endoscopic techniques.2,5 Other reported treatments are antrectomy, which involves greater morbidity and mortality, and medical treatments with hormones, steroids, or tranexamic acid. The latter have not been efficacious, given that they require long-term management and cause adverse effects and relapse when suspended. Some reports state that acute bleeding has been controlled with octreotide.2,5,6 There is little information on the use of APE in children for managing bleeding caused by GAVE. Our cases did not present with complications.

We can conclude that APE in children with GAVE, as in adults, is useful for controlling active bleeding, without causing serious complications. The pathology should be suspected in children presenting with gastrointestinal bleeding that causes anemia, who are undergoing treatment with immunosuppressants and/or have an autoimmune disease. Biopsy may not always report vascular lesions. An endoscopic image characteristic of GVE with no other etiology for gastrointestinal bleeding that responds favorably to APE treatment supports the diagnosis. GAVE should be considered a cause of gastrointestinal bleeding in the pediatric population.

Financial disclosureNo financial support was received in relation to this study.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Membreño-Ortíz G, Miranda-Barbachano K, Flores-Calderón J, González-Ortíz B, Siordia-Reyes G. Ectasia vascular gástrica en niños: reporte de casos. Revista de Gastroenterología de México. 2016;81:232–233.