Mastocytosis is a rare disease characterized by the anomalous proliferation and accumulation of mast cells in one or more organs. Activating mutations of the c-KIT receptor tyrosine kinase gene is the postulated pathogenesis; the D816V mutation has been detected in more than 90% of cases. Mast cell accumulation can be produced at the level of the skin (cutaneous mastocytosis) or other organs (systemic mastocytosis [SM]), including gastrointestinal involvement.1

A 73-year-old man, with an unremarkable past medical history, was referred from the cardiology service for anemic syndrome study. The outstanding finding in the physical examination was splenomegaly. A computed tomography (CT) scan revealed an enlarged 23cm spleen and abdominal and mediastinal lymphadenopathy. Bone marrow biopsy was performed, and immunohistochemistry (IHC) testing identified the presence of abnormal mast cells that were positive for CD68, CD117, and tryptase, with a positive cKIT mutation (D816V). The patient was diagnosed with SM associated with monoclonal hemopathy involving the skin, spleen, lymph nodes, bone, and bone marrow. Because there was no clinical progression, periodic follow-up with no treatment was decided upon.

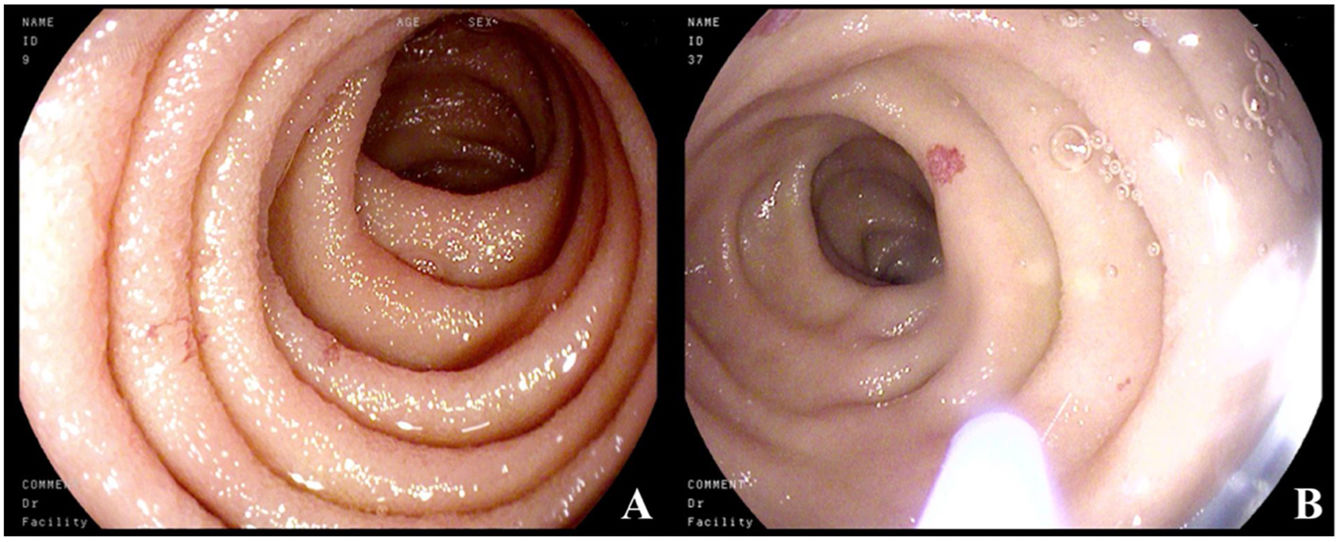

Five years later, the patient was admitted to the gastroenterology service due to microcytic anemia (hemoglobin 9.6g/dl), melena of 15-day progression, and chronic diarrhea. Microbiologic studies were negative. Endoscopic studies were carried out, in which gastroscopy revealed millimetric pseudovascular lesions in the second part of the duodenum that were friable when touched. Suspected to be the cause of the gastrointestinal bleeding, the lesions were photocoagulated with argon plasma (Fig. 1A and B); colonoscopy findings were unremarkable. Random biopsies of the digestive tract were taken during the two studies and showed dense cellular accumulations, with foci of more than 15 anomalous mast cells. IHC revealed cKIT and tryptase positivity, CD30+, and CD2–, consistent with gastrointestinal involvement of the SM.

(A) Normal mucosa of the second part of the duodenum, with millimetric erythematous lesions. (B) Catheter for applying argon plasma. The normal mucosa is interspersed with millimetric, rounded, pseudovascular, erythematous lesions with spontaneous bleeding from the passage of the endoscope.

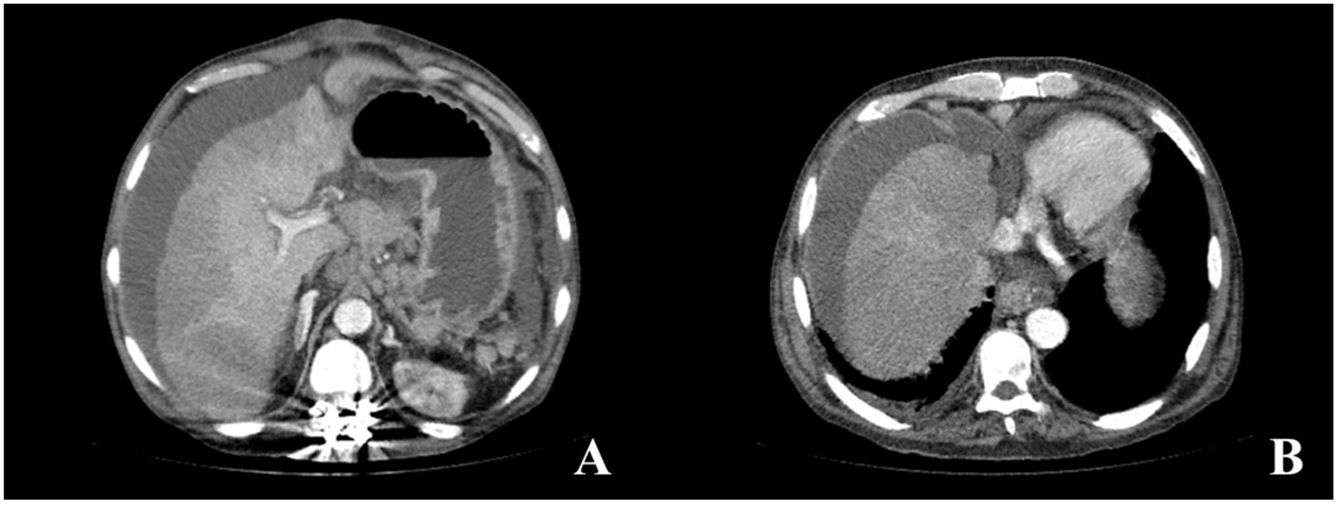

Six months later, the patient arrived at the emergency room for the sudden onset of abdominal pain. Abdominal CT scanning identified chronic thrombosis of the suprahepatic veins and inferior vena cava, development of collateral veins, chronic liver disease, and ascites, all suggesting chronic Budd–Chiari syndrome (Fig. 2A and B). The patient’s condition worsened within a few hours, presenting with fever and hemodynamic instability. Antibiotic and vasoactive amines were started. He developed septic shock, and because there was no clear diagnosis from the imaging study, emergency laparotomy was performed, identifying fecaloid peritonitis and complete circumferential rupture, 10cm from the angle of Treitz, of an intestinal segment opening into the cavity. Given the situation of generalized peritonitis and refractory septic shock in a patient with chronic, aggressive, and incurable disease, only surgical damage control was carried out (resection of the affected intestinal segment and primary closure of the perforation). The patient died a few hours later due to multiorgan failure. The histopathologic study of the surgical specimen confirmed that the intestinal perforation was secondary to the accumulation of abnormal mast cells, with the D816V mutation of the c-KIT gene.

Abdominal CT images with intravenous contrast material in the portal phase, axial MIP reconstruction. (A and B) Signs of chronic liver disease, chronic thrombosis of the suprahepatic veins and inferior vena cava, development of collateral perigastric and perihepatic veins, as well as ascites in all the compartments.

The term mastocytosis refers to a heterogeneous group of diseases characterized by the anomalous proliferation of mast cells, whose presentation and clinical symptoms vary, depending on the affected organ. Clinical manifestations are related to the release of mast cell mediators, tissue infiltration, or the presence of another associated hematologic disorder. Mast cell degranulation conditions the release of histamine, tryptase, prostaglandins, and leukotrienes, causing episodes of hypotension, syncope, headache, diarrhea, abdominal pain, erythema, rash, angioedema, and in severe cases, anaphylactic shock.1–2 Of the patients with SM, 30–80% present with gastrointestinal symptoms.3 Liver infiltration that conditions hepatomegaly, with or without portal fibrosis, occurs in 5–15%, whereas a resulting portal hypertension and ascites is uncommon (4%). Budd-Chiari syndrome is described in the literature as an extremely rare manifestation. Intestinal involvement presents in up to 80% of patients, with infiltration of the wall and atrophy of the villi, causing symptoms of malabsorption, with chronic diarrhea and steatorrhea. It can also present as a syndrome similar to NSAID-induced enteropathy, with nausea and vomiting (28%), abdominal pain (50%), and erosions and ulcers that cause gastrointestinal bleeding (11%).3,4 The most frequent endoscopic findings in SM are dotted violet-colored lesions, “rash-like” papules, and edematous and erythematous mucosa with a thinned wall.5 In our case, intestinal perforation was secondary to mast cell infiltration that caused inflammation, fibrosis, stiffness, and weak areas in the intestinal wall. SM is diagnosed by demonstrating mast cell infiltration in the affected tissues and the presence of the KIT gene mutation. Endoscopic and radiologic findings, albeit nonspecific, can aid in making the diagnosis.1,2

The therapeutic goal is to prevent mast cell degranulation and control the secondary symptoms, utilizing antihistamines, stabilizers, leukotriene inhibitors (montelukast), proton pump inhibitors (omeprazole), corticosteroids and/or anti-IgE monoclonal antibodies (omalizumab).6 In aggressive, as well as individualized forms, cytoreductive treatment (cladribine),2 tyrosine kinase inhibitors (imatinib and nilotinib),7 midostaurin,8 and avapritinib9 have produced promising results. Some patients can be candidates for bone marrow transplantation.

In conclusion, we described herein the case of a patient with SM associated with monoclonal hemopathy, who presented with intestinal perforation in the context of massive mast cell infiltration at the gastrointestinal level, an extremely rare entity in clinical practice.

Ethical considerationsThis is the description of a clinical case; it is not a clinical trial and no experiments have been carried out on humans or animals.

The authors declare they have followed the protocols of their work center, (Hospital Universitario Central de Asturiasfor clinical case publication), have preserved patient anonymity.

Informed consent was not requested for the publication of this case because it contains no personal data that could identify the patient.

Financial disclosureNo financial support was received in relation to this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Carballo-Folgoso L, Cuevas-Pérez J, Blanco-García L, Celada-Sendino M, Castaño-Fernández O. Perforación intestinal secundaria a mastocitosis sistémica: reporte de un caso excepcional. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2023;88:450–452.