The aim of the Mexican Consensus on the Treatment of HepatitisC was to develop clinical practice guidelines applicable to Mexico. The expert opinion of specialists in the following areas was taken into account: gastroenterology, IFNectious diseases, and hepatology. A search of the medical literature was carried out on the MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CENTRAL databases through keywords related to hepatitisC treatment. The quality of evidence was subsequently evaluated using the GRADE system and the consensus statements were formulated. The statements were then voted upon, using the modified Delphi system, and reviewed and corrected by a panel of 34 voting participants. Finally, the level of agreement was classified for each statement. The present guidelines provide recommendations with an emphasis on the new direct-acting antivirals, to facilitate their use in clinical practice. Each case must be individualized according to the comorbidities involved and patient management must always be multidisciplinary.

El objetivo del Consenso Mexicano para el Tratamiento de la HepatitisC fue el de desarrollar un documento como guía en la práctica clínica con aplicabilidad en México. Se tomó en cuenta la opinión de expertos en el tema con especialidad en: gastroenterología, IFNectología y hepatología. Se realizó una revisión de la bibliografía en MEDLINE, EMBASE y CENTRAL mediante palabras claves referentes al tratamiento de la hepatitisC. Posteriormente se evaluó la calidad de la evidencia mediante el sistema GRADE y se redactaron enunciados, los cuales fueron sometidos a voto mediante un sistema modificado Delphi, y posteriormente se realizó revisión y corrección de los enunciados por un panel de 34 votantes. Finalmente se clasificó el nivel de acuerdo para cada oración. Esta guía busca dar recomendaciones con énfasis en los nuevos antivirales de acción directa y de esta manera facilitar su uso en la práctica clínica. Cada caso debe ser individualizado según sus comorbilidades y el manejo de estos pacientes siempre debe ser multidisciplinario.

Specific questions about therapy were identified and addressed by the participants, based on scientific evidence on hepatitis C management collected from a systematic review of the literature. The development process of the present guidelines took nine months and the first meeting of the steering committee was in September 2016. The face-to-face meeting of the working group of the consensus was held in October 2016 and the presentation of the manuscript for its publication took place in May 2017.

Sources and searchesPhysicians at the Department of Gastroenterology of the Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León performed a systematic search on MEDLINE (starting from 1946), EMBASE (starting from 1980), and CENTRAL (Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials) up to August of 2016. The search terms were: hepatitis C, interferon, ribavirin, sofosbuvir, ledipasvir, velpatasvir, daclatasvir, asunaprevir, simeprevir, dasabuvir, ombitasvir, paritaprevir, ritonavir (3 D), elbasvir, and grazoprevir. The search was limited to studies published in English and conducted on humans.

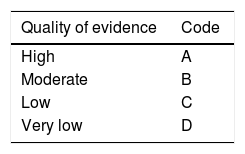

Review and grading of evidenceThe quality of evidence was evaluated according to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system (Table 1) and carried out by three methodologists (Dr. Roberto Monreal, Dr. Omar David Borjas and Dr. Emmanuel González), who did not vote on the statements. They determined the risk of bias in the individual studies, the risk of bias between studies, and the quality of evidence in general of the studies identified for each statement. The voting members of the working group of the consensus reviewed the GRADE criteria and agreed upon them at the meeting. The quality of evidence for each statement was graded as: high, moderate, low, and very low. The evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) was classified as high-quality but could be downgraded for the following reasons: heterogeneity between the outcomes of individual studies, ambiguous results, indirect study results, reported bias, or a high risk of bias between the studies supporting a statement. The data from cohort studies or case-control studies were initially categorized as having a low quality of evidence but could be downgraded through the same criteria applied to the RCTs or upgraded if a very great treatment effect or a dose-response relation was identified, or if all the plausible biases had a tendency to change the magnitude of the effect into the opposite direction. Product approval and labeling by governmental regulatory agencies vary among countries, and although they were not ignored, the recommendations were based on the evidence in the medical literature and the consensus discussions and may not fully reflect the labeling of products in Mexico.

The consensus processThe working group of the consensus was made up of 34 voting participants that included academic and community-based gastroenterologists, hepatologists, and specialists in infectious diseases with experience in various aspects of hepatitis C management, as well as a non-voting facilitator (Dr. Francisco Bosques). The working subgroups and co-presidents of the meeting (Dr. Aldo Torre Delgadillo, Dr. Graciela Castro Narro, Dr. René Malé Velázquez, and Dr. Rafael Trejo Estrada) developed the initial statements. A web-based platform supported by the Asociación Mexicana de Hepatología (AMH) was used to facilitate the majority of the aspects of the consensus process before the face-to-face meeting. Through the consensus platform, the working groups: 1) reviewed the initial literature search and identified the relevant references that were selected and linked (“tagged”) to each statement; 2) used a modified Delphi process for anonymous voting on the level of agreement of the statements; 3) suggested statement revisions; and 4) provided comments on specific references and background data. The statements were revised through two separate iterations and finally at the consensus meeting. Every participant had access to all the abstracts and electronic copies of the individual “tagged” references. The GRADE criteria in relation to the evidence for each of the statements were given at the meeting. The working group attended a 2-day consensus conference in Mexico City in October 2016, in which the data were presented, the statements were discussed, their final versions were written, and the participants voted on the level of agreement for each statement. A scale from 1 to 5 (in which 1, 2, and 3 indicated “in complete disagreement”, “in disagreement”, and “uncertain”, respectively) was employed and a statement was accepted if > 75% of the participants voted 4 (in agreement) or 5 (in complete agreement). The strength of each recommendation was assigned by the working group of the consensus through the GRADE system as strong (“…is recommended”) or weak (“…is suggested”). The strength of recommendation consisted of four components (risk/benefit balance, patient values and preferences, resource cost and allocation, and quality of evidence). Thus, it was possible for a recommendation to be classified as strong, despite being supported by a low quality of evidence or weak, despite being supported by a high quality of evidence.

Based on the GRADE system, a strong recommendation indicates that the statement can be applied in the majority of cases, whereas a weak recommendation means that clinicians “should recognize that different options are appropriate for different patients and should help each patient decide on the treatment that is consistent with his or her values and preferences”. The characteristics of the GRADE system are shown in Table 1.

The manuscript was integrated and edited by Dr. Francisco Bosques, along with Dr. Roberto Monreal, Dr. Omar Borjas, and Dr. Emmanuel González. It was then reviewed by the steering committee members before being distributed to all the participants for their review and approval. Potential conflict of interest is expressed in writing and presented according to AMH policy and is available to all the consensus working group members and readers. The Consensus document consists of 19 sections that address different clinical scenarios and the quality of evidence and strength of recommendation are shown for each statement, as well as the level of agreement, expressed as a percentage, that was obtained through the voting of all the participants at the face-to-face meeting.

Treatment indications: who should and who should not be treated?Recommendations- •

All patients with chronic HCV infection should be considered for treatment, whether or not they have been previously treated (A1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 100%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 0%.

For complete and satisfactory elimination of the hepatitis C virus (HCV), it is necessary to have a solid plan involving the entire country and to have the resource availability and support of the healthcare sector to have effective and easily-accessed treatments. The benefit of curing the infection has important clinical advantages. The goal of treatment is to define a sustained virologic response (SVR) as the persistent absence of HCV for at least 12 weeks after treatment completion. That was demonstrated in a prospective study in which the majority of patients achieved an SVR that lasted for more than 5 years, through a first-line HCV treatment, showing that recurrence was rare after a prolonged follow-up period.1

Patients with SVR have an excellent clinical response, manifested by a significant decrease in fatigue, improved physical activity, a biochemical response with normalized aminotransferase levels, and reduced fibrosis progression.

Over the last 5 years, the treatment of chronic HCV infection has improved considerably with the introduction of new direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) that are targeted at different sites of the viral genome, preventing the replication cycle.2

Recommendation- •

Treatment should be a priority for patients with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis (METAVIR F-3 F-4) (A1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 95%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 5%.

Today, patients with advanced disease can receive treatment. That group of patients is at greater risk for complications due to hepatic decompensation (encephalopathy, ascites, gastrointestinal bleeding from esophageal varices, and the appearance of hepatocellular carcinoma). The HALT-C study, supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, demonstrated a rise in hepatocellular carcinoma development in patients with chronic hepatitis C under long-term surveillance, with mortality rates increasing 7.5 to 10% per year.3

SVR has been shown to reduce decompensation episodes in patients with advanced disease. There is less need for liver transplantation and a lower mortality rate in patients with advanced liver disease that have SVR, than in untreated patients.3,4 Those data have been reproduced in a European study,5 but there are still no long-term results.

Recommendations- •

Expedited treatment is recommended for patients with cirrhosis of the liver that have Child-Pugh class A or B disease. Patients with decompensated cirrhosis (Child-Pugh class B and C) should also be urgently treated with an IFN-free regimen, even if they are not going to undergo transplantation. Patients with Child-Pugh class C and a MELD score above 20 that are indicated for liver transplantation can undergo the transplant first, and then receive treatment (B1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 96%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 4%.

IFN use is absolutely contraindicated for patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Post-liver transplantation IFN use is currently not indicated, due to multiple adverse effects and the low SVR rate. With the introduction of the new DAAs, treatment is more effective, with better pretreatment and posttreatment response.

Liver transplantation is the treatment of choice for patients with advanced cirrhosis. It is well-known that post-transplantation hepatitis C recurrence is universal and is associated with reduced graft survival.6 Whether decompensated patients with chronic liver disease should receive pretransplantation or posttransplantation treatment is a subject of debate. At present, there are no controlled studies on which to base an ideal time of treatment.

Prevention of post-transplantation graft infection in patients waiting for liver transplantation is attempted by having them achieve SVR and biochemical response, thus reestablishing liver function. An initial analysis was conducted in France on transplantation waiting list patients that had MELD scores above 14 points. The authors of that study showed that sofosbuvir and ribavirin were well tolerated and SVR was achieved in > 70% of the cases.7 Patients with a history of decompensations or functional Child-Pugh class B or C should not receive treatment with protease inhibitors, due to the toxicity of those antivirals. It is recommended to use only a combination of sofosbuvir plus an NS5A inhibitor.8

Patients with a MELD score > 18-20 should undergo upfront primary liver transplantation, and then be treated. Depending on the transplantation center, patients on the waiting list for more than 6 months can be treated to obtain the benefits of virus elimination.9

Recommendations- •

Treatment should be a priority in patients with any of the following conditions: HIV or HBV coinfection; pre-transplantation or post-transplantation status; clinically significant extrahepatic manifestations (symptomatic vasculitis associated with mixed HCV-related cryoglobulinemia); nephropathy due to immune complexes related to HCV and B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma; and debilitating fatigue (A1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 95%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 5%.

Patients coinfected with HIV and treated with DAAs have a similar response to those infected only with HCV. Therefore, the former should be treated as if they only had HCV infection, in conjunction with infectious diseases specialists.10,11

There are several management modalities and response rates are similar. The daclatasvir + sofosbuvir regimen was evaluated over a 12-week period in the ALLY-2 study on a group of patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. Some of the patients were treatment-naïve and others were treatment-experienced. The patients were stratified by HCV genotype (1/83%, 2/9%, 3/6%, 4/2%) and doses were adjusted according to the concomitant antiretroviral treatment. Ninety-seven percent of the treatment-naïve patients had SVR, as did 98% of the treatment-experienced patients.12 In the non-randomized open C-EDGE CO-INFECTION study,13 the grazoprevir/elbasvir regimen was evaluated in treatment-naïve patients infected with HCV genotypes 1, 4, or 6 and HIV with or without cirrhosis, resulting in a 96% SVR12 (in 210/218 patients). In the phase II ERADICATE14 study, the ledipasvir/sofosbuvir regimen was assessed in a small group of 50 patients with no cirrhosis. The treatment-naïve group achieved 100% SVR12 (13/13) and the treatment-experienced group had 97% SVR12 (36/37). There is not enough information for treating those patients for 8 weeks, and therefore it is not recommendable to consider short periods. In the TURQUOISE-1 study,11 the combination of paritaprevir/ritonavir/ombitasvir + dasabuvir was evaluated in treatment-naïve and treatment-experienced patients, resulting in SVR12 of 93% and 90-96%, respectively. The COSMOS study 15 produced similar results with the simeprevir/sofosbuvir regimen in patients with genotype 1b infection (92% SVR). Finally, patients with genotypes 1-4 treated with the combination of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir had 100% SVR12.16

Patients coinfected with hepatitis B tend to have a low viral load, making HCV the central focus of treatment. Nevertheless, HBV can reactivate after virus C clearance. Thus, all patients that start treatment with a DAA should have a complete HBV viral panel that includes the DNA of the virus. If the results are positive or there is evidence of occult hepatitis B, treatment should be begun with nucleoside/nucleotide analogs to prevent hepatitis B virus reactivation. Patients coinfected with hepatitis B/C should be treated with a regimen similar to that used in patients with HCV monoinfection.

Those subjects with occult hepatitis B (positive for anti-HB core antigen, but negative for HBsAg and anti-HBs) are at risk for reactivation as soon as they are in treatment for HCV. 17–19 Monitoring of ALT and AST levels is recommended every 4 weeks in patients positive for isolated anti-HB core antigen, during DAA treatment for HCV. If there is an increase > 2-fold the upper limit of normal, HBV DNA levels should be determined, and if positive, treatment for HBV should be considered. Treatment for HBV should begin before (preferably 2 to 4 weeks before) or concomitant with the start of DAA treatment for HCV. The recommended treatment for HBV is entecavir 0.5mg PO once-daily or tenofovir 300mg PO once-daily. Treatment for HBV should be continued for at least 3 weeks after completing DAA treatment for HCV. If the patient has no indication for chronic HBV treatment, treatment for HBV can be discontinued.

DAA and immunosuppressant use, including rituximab, has shown good response in patients with mixed cryoglobulinemia and HCV.20 Non-Hodgkin lymphoma can be associated with HCV and the diffuse B-cell variant is the most common. Lymphoma should be treated with the customary regimen (R-CHOP) plus rituximab. However, rituximab can increase viral replication. Isolated cases of lymphoma remission with antiviral therapy for HCV eradication have been reported.21

There is an association between HCV and immune complex-mediated kidney damage with vasculitis and focal glomerulosclerosis. Those cases should be managed with antivirals adjusted to the grade of kidney damage, in addition to rituximab, plasmapheresis, steroids, and cyclophosphamide. There is no evidence at present of a rapid response to treatment with DAAs, and as stated above, rituximab can be useful. Multidisciplinary management is recommended in such cases.

Recommendation- •

Treatment should be a priority in individuals at risk for transmitting HCV, such as: intravenous drug addicts, homosexuals with high-risk sexual practices (promiscuity, several partners, unprotected sex, sex with persons infected with HBV, herpes virus, or HIV), women trying to get pregnant, patients on hemodialysis, and prisoners (B1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 91%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 9%.

HCV transmission is unlikely in patients that have experienced cure. The most common risk for acquiring HCV is injection drug use. De novo HCV infection in subjects that are injection drug users (IDUs) is above 70%.22 In a meta-analysis that evaluated the results of HCV treatment (based on pegylated interferon [pegIFN]) in IDUs, 37% SVR was reported for the patients with genotype 1 or 4, and 67% with genotypes 2 or 3.23 Unfortunately, there is little information on treatment with DAAs and the exact prevalence of reinfection is unknown. Likewise, that group of patients requires a multidisciplinary approach that includes a psychiatrist, a specialized drug and alcohol abuse department, an infectious diseases specialist, and aspects of intense social work.

High-risk homosexuals are defined as those that are promiscuous, have sexual contact with several partners or with partners infected with HBV, HCV, or HIV, that engage in unprotected sex, and men with HIV infection that have sex with men.22,24 Opportune recognition and treatment of HCV infection in that special group of patients is a determining factor in the prevention of later infections, including that of acute HCV. Those patients should receive immediate treatment, as well as information on their disease, so they do not infect other sexual partners.25

Persons in prison are another special group of great epidemiologic importance due to risk for transmission and they have poor access to HCV treatment. Studies conducted in the United States show that seroprevalence varies from 30 to 60%, and of those cases, acute infection occurs in 1%.26 The use of older treatments in that group of patients is not free from side effects and most certainly antiviral therapy could change HCV incidence and reinfection rates, given that many of those patients are IDUs.

In women that wish to become pregnant, there is no possibility of maternal-fetal transmission if the mother does not present with viremia. Those patients can receive treatment before becoming pregnant, but treatment should not be given during pregnancy.

Recommendation- •

Patients with moderate fibrosis (F2) should receive treatment (A2).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 100%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 0%.

It is very useful to treat patients with moderate fibrosis because it reduces liver fibrosis progression, which is one of the basic goals of HCV treatment, and thus treatment should not be delayed. Treatment improves quality of life and increases life expectancy. Noninvasive serologic tests and imaging studies provide better information on early disease-stage patients.27,28

Recommendations- •

Patients infected with HCV, with or without mild fibrosis (METAVIR F0 F1) and with no extrahepatic manifestations, should receive treatment, but the time of treatment can be individualized (B1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 88%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 12%.

Beginning treatment in disease stages F0 or F1 increases the SVR rate.

In the past, when patients were treated with interferon (IFN) and ribavirin, the SVR rate was influenced by fibrosis grade, and was more favorable in cases of early-stage fibrosis. Today, with the use of DAAs, that is no longer as relevant.

Patients with early-stage fibrosis documented through biopsy benefit from treatment. In a preliminary study by Jezequel et al.,29 after a 15-year follow-up, they showed greater survival in the treated patients (93%) that had SVR. Survival was lower in the patients that did not respond to treatment (82%) and in untreated patients (88%). Fibrosis progressed 15% in the patients with treatment delay.

Treatment should be individualized in patients with early-stage liver disease (compensated patients with Child A). We believe it is important to evaluate the best therapy or therapies accessible in Mexico and carefully study the group of patients that “can wait” (risk-benefit) in relation to treatment. Unfortunately, there is no solid evidence from Mexican analyses on the theme. Other studies have documented reduced mortality rates and complications, with quality of life improvements upon achieving SVR, in patients receiving treatment at early stages of fibrosis.30–32

Recommendation- •

Treatment should be individualized in patients with a limited life expectancy due to non-hepatic comorbidities (B1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 100%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 0%.

There are patients with a very limited life expectancy due to age or severe comorbidities with a short natural history. In those patients, treatment for HCV, as well as liver transplantation or other therapy that does not change the course of their progression, should not be recommended.33,34

Hepatitis C virus treatment goalsThe immediate goal of HCV treatment is SVR, defined as the persistent absence of HCV RNA for at least 12 weeks after the end of treatment. SVR is a marker for HCV infection cure and has been shown to be lasting in more than 99% of patients treated with IFN that have had follow-up of 5 years or more. At present, that benefit has not yet been corroborated in patients receiving treatment with DAAs. Serum anti-HCV antibodies are persistent in patients with SVR, but HCV RNA is no longer detected in serum or in liver tissue, reaching substantial improvement in liver histology.

Both SVR12 and SVR24 have been accepted as HCV treatment goals, given that their concordance is > 99%.35 HCV core antigen that is undetectable 12 or 24 weeks after treatment completion can be used as an alternative to HCV RNA testing to evaluate SVR12 or SVR24.36 Patients that are cured of HCV infection experience benefits in their general state of health that include reduced liver inflammation and a decrease in the progression rate of liver fibrosis and portal hypertension. SVR is associated with a reduction > 70% in the risk for hepatocellular carcinoma and a 90% decrease in the risk for hepatopathy-related death and the need for liver transplantation.3 The cure of HCV infection also reduces symptoms and mortality derived from severe extrahepatic manifestations related to chronic HCV infection. Given the multiple benefits associated with successful HCV treatment, those patients should receive antiviral therapy, with the aim of achieving SVR, preferably at an early stage in the course of chronic infection before the development of severe liver disease or other complications. Numerous studies have shown that HCV treatment that achieves SVR in patients with advanced liver disease (METAVIR F3-F4) results in reduced rates of liver decompensation, hepatocellular carcinoma development, and death. In the HALT-C study, patients with advanced fibrosis that achieved SVR had less need for liver transplantation, a lower hepatopathy-related morbidity and mortality rate, and a lower frequency of hepatocellular carcinoma, when compared with patients that had similar fibrosis grades but did not achieve SVR.37 It should be pointed out that persons with advanced liver disease require long-term follow-up and continuous surveillance with respect to the possible appearance of hepatocellular carcinoma, regardless of treatment result. Real-world multicenter studies in patients with decompensated cirrhosis treated with DAAs have shown that approximately one-third of patients have an improved MELD score, a reduced frequency of decompensation events, and can even be taken off the transplantation list, especially if their MELD score is < 18-20. However, the long-term clinical benefit has not been evaluated in all the studies.38

Recommendations- •

The goals of treatment are to cure the hepatitis C infection, prevent cirrhosis of the liver and its decompensation, and to prevent the development of hepatocellular cancer (HCC), severe extrahepatic manifestations, and death. Treatment goals also include the prevention of disease transmission, as well as recurrence after liver transplantation (A1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 100%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 0%.

- •

The goal of treatment is to achieve an undetectable level of HCV RNA through a sensitivity test (≤ 15 IU/ml) at 12 weeks (SVR12) or 24 weeks (SVR24) after treatment completion (A1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 91%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 9%.

- •

HCV eradication reduces the decompensation rate and reduces, but does not eliminate, the risk for HCC in patients with advanced fibrosis or compensated cirrhosis. Surveillance for complications and HCC should be continued in those patients (A1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 100%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 0%.

- •

HCV eradication reduces the need for transplantation in patients with decompensated cirrhosis that have a MELD score of 18-20. It is not known whether HCV eradication modifies medium-term and long-term survival in that group of patients (B2).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 100%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 0%.

Pre-therapeutic evaluationAll patients with HCV infection that wish to receive treatment and have no contraindications for it, whether treatment-naïve or treatment-experienced or with compensated or decompensated chronic liver disease, should be treated.

There should be no delay in the treatment of patients with significant fibrosis or cirrhosis, including patients with decompensated cirrhosis, those with clinically important extrahepatic manifestations, patients with recurrence after liver transplantation, those at risk for rapid deterioration of liver disease due to comorbidities, and individuals at risk for disease transmission.

Patients with a limited life expectancy due to hepatopathy should be managed in conjunction with an expert that, if possible, is in contact with a transplantation center. Treatment is not recommended in patients with a limited life expectancy due to comorbidities unrelated to liver disease.

Factors associated with a possibly accelerated progression of liver fibrosis should be evaluated, such as inflammation grade, patient age, HCV progression time, male sex, a history of transplantation, alcohol consumption, fatty liver disease, obesity, insulin resistance, genotype 3, and coinfection with HBV or HIV.

Liver biopsy, imaging studies and/or non-invasive markers to determine the presence of advanced fibrosis are recommended in all patients with HCV infection to facilitate the appropriate decision as to treatment strategy and to determine the need to begin additional measures for the management of cirrhosis.39 Liver fibrosis grade is one of the most important outcome factors for predicting HCV disease progression.40 In some cases, treatment duration is longer in patients with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis.

Liver biopsy is the diagnostic method probably considered the gold standard, but the possibility of sampling errors, interobserver variability, and the invasive nature of the modality that is not exempt from complications, are all factors that limit its use. Noninvasive tests for establishing liver fibrosis grade in patients with chronic HCV infection include models that incorporate serum biomarkers, direct serum biomarkers, and liver elastography.

Transitory elastography is a noninvasive form of measuring liver stiffness and it correlates well with substantial fibrosis or cirrhosis measurement in patients with chronic HCV infection.41 The most effective approach for evaluating fibrosis grade is probably the combination of direct biomarkers and transitory elastography. Liver biopsy should be considered when conflicting results between the 2 modalities affect clinical decisions or if other causes are suspected. Patients with clinically evident cirrhosis do not require additional stratification studies.

HCV RNA detection is indicated in patients that are candidates for antiviral treatment. Quantification should be carried out through a sensitivity assay (≤ 15 IU/ml) and expressed in IU/ml. HCV genotype, including the genotype 1 (1a or 1b) subtype should also be assessed before starting treatment. However, it is important to know that there are DAA combinations that are pangenotypic (sofosbuvir/velpatasvir and sofosbuvir/daclatasvir), as well as combinations that are non-panogenotyptic (sofosbuvir/ledipasvir, ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir/dasabuvir, grazoprevir/elbasvir) that are equally effective in genotype 1 disease, with no distinction between subtypes 1a and 1b.

Genotype IL28B has lost predictive value with the advent of treatment regimens based on IFN-free direct-acting antivirals. Thus, that test is only useful when pegylated IFN and ribavirin are the only treatment options.

The systematic determination of HCV resistance prior to treatment commencement is not recommended, because it could limit access to management since treatment regimens can be optimally designed, even without that information.42 However, the presence of certain resistance (NS5A RAVs) significantly reduces SVR12 rates in the 12-week treatment regimen with elbasvir/grazoprevir in patients with genotype 1a infection. Based on the knowledge of an inferior response, resistance testing is recommended in patients with genotype 1a that are being considered for that regimen. If resistance is demonstrated, treatment extension to 16 weeks with the addition of weight-adjusted ribavirin is recommended to reduce the possibility of relapse.42

Recommendations- •

All patients with confirmed HCV infection and viral load should be treated unless there is a contraindication (A1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 100%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 0%.

- •

Comorbidities that influence liver disease progression should be evaluated and treated (A1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 100%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 0%.

- •

Liver disease stage should be evaluated before beginning treatment. It is indispensable to identify the patients with cirrhosis because its prognosis is different, and treatment must be modified (A1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 100%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 0%.

- •

The grade of fibrosis must be evaluated. It can first be done through noninvasive methods. Liver biopsy should be considered when there is diagnostic doubt or suspicion of other associated causes (A1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 95%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 5%.

- •

HCV RNA should be identified and quantified through a sensitivity test capable of detecting ≤ 15 IU/ml (A1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 100%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 0%.

- •

It is essential to identify HCV genotype and subtype (1a-1b) before beginning treatment. It is a crucial factor in choosing the treatment regimen (A1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 100%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 0%.

- •

The new direct-acting antivirals have made IL28B genotype testing for predicting treatment response unnecessary (A1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 92%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 8%.

- •

Determining the baseline resistance-associated polymorphism is unnecessary in patients that have not had previous treatment with DAAs. It should only be considered in patients with treatment regimens that include elbasvir/grazoprevir or daclatasvir/asunaprevir (B1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 100%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 0%.

Treatment of hepatitis C virus genotype 1Amazing progress has been made in the treatment for the eradication of chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Without a doubt, improvement in the cure rates with the different treatment regimens has had a favorable impact on outcome and quality of life of infected patients, changing the course of a disease that affects a large number of patients worldwide. This medical breakthrough will surely impact the history of medicine.43,44 Patients with genotype 1 were considered the most difficult to treat, given the low sustained virologic response at 24 weeks from the end of treatment (SVR24) with pegIFN and ribavirin (RBV), with even poorer response in patients with cirrhosis of the liver. Many patients with advanced liver disease were not considered candidates for that therapy due to its adverse effects.45 Today, the new treatments based on direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) can be administered to patients with advanced liver disease, not only improving SVR, but also survival rates and liver function9,46 Some of the DAAs are available in Mexico: asunaprevir (ASV), ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir and dasabuvir (OBV/PTV/r/DSV), daclatasvir (DCV), simeprevir (SMV), sofosbuvir (SOF), and the combination of sofosbuvir/ledipasvir (SOF/LDV) and grazoprevir/elbasvir (GZV/EBV). Other drugs have been accepted in North America, Europe, and Asia, and although not yet available in Mexico, their process of acceptance has begun. One such case is sofosbuvir/velpatasvir (SOF/VEL). Therefore, the consensus working group decided to include the drugs that are currently available in Mexico, as well as those that are in the process of acceptance, in its recommendations.

Double therapy based on pegIFN + RBV and the triple therapy with pegIFN + RBV + simeprevir are currently considered alternative therapies because their SVR rates are lower than those achieved with interferon-free regimens, and consequently, are recommended only in cases in which there are access limitations to the new DAA drugs.9,46,47 Notwithstanding, the consensus working group believes that the risk for progression in patients with fibrosis stages F3 or F4 must be considered when treatments with suboptimal efficacy are contemplated.9,46,47 Triple therapy with first generation protease inhibitors (boceprevir or telaprevir) is considered unacceptable because of the high percentage of adverse effects.9,46 The Mexican Consensus on Hepatitis C, previously published in 2015, provides a detailed description of IFN-based double therapy and triple therapy with simeprevir.45 It is important to specify that the majority of current treatments achieve SVR12 rates above 90%. Therefore, any treatment with lower SVR rates should be regarded as alternative therapy and recommended only in cases where access to therapeutic regimens with a high SVR rate is difficult.48

Genotype 1 infectionTherapies based on interferonThe consensus working group includes therapy based on pegIFN + RBV and SMV for 12 weeks in its recommendations.45

Recommendations- •

Regimens based on pegIFN/RBV or pegIFN/RBV/SMV are recommended in patients with no previous treatment history, without cirrhosis or with compensated cirrhosis, and only when there is no access to IFN-free regimens with direct-acting antivirals (A1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 92%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 8%.

- •

If there is no access to IFN-free regimens with direct-acting antivirals, regimens based on pegIFN/RBV or pegIFN/RBV/SMV are a therapeutic alternative, according to the 2015 Mexican Consensus on the Diagnosis and Management of Hepatitis C (A1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 96%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 4%.

Therapy with pegylated interferon plus ribavirin plus sofosbuvir- •

Patients with genotype 1 infection that do not have cirrhosis can be treated with a combination of weekly pegIFN, a daily weight-based dose of ribavirin (1,000 or 1,200mg in patients < 75kg or ≥ 75kg, respectively), and sofosbuvir (400mg daily) for 12 weeks (A1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 100%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 0%.

The triple therapy regimen based on pegIFN, ribavirin, and sofosbuvir was evaluated in the NEUTRINO study49 that included treatment-naïve patients. The SVR in that study was 89% (259/291): 92% (207/225) in subtype 1a and 82% in subtype 1b (54/66). A lower SVR was observed in the patients with cirrhosis of the liver (80%), compared with patients that did not have cirrhosis (92%). The SVR in patients previously treated with pegIFN and ribavirin and treated with the above regimen was calculated using mathematical modeling, taking the NEUTRINO study results into account. Based on those variables, the mathematical model supposes a 78% SVR in patients with previous double-therapy failure.50 The SVR12 rate with the triple therapy based on pegIFN, RBV, and SOF was 79% in the patients that did not achieve SVR after receiving pegIFN, RBV, and a protease inhibitor under study.51 The TRIO study included real-life patients, 42% of whom were treatment-experienced and 58% treatment-naïve. SVR12 was 81% (112/138) in treatment-naïve patients that did not present with cirrhosis of the liver. In treatment-naïve patients with cirrhosis, SVR was 81% (25/31), and it decreased to 77% (30/39) in treatment-experienced patients with no cirrhosis, and to 62% (53/85) in treatment-experienced patients with cirrhosis.52

The C-EDGE study showed that a DAA regimen (grazoprevir/elbasvir) had a better safety profile and SVR12 rate than the triple therapy based on pegIFN + RBV + SOF.42 The C-EDGE is an important study because it compares an IFN-free therapy with an IFN regimen that contains a DAA that is not a protease inhibitor or an NS5A inhibitor. The SVR in genotype 1a was 100% in the patients treated with GZP/EBV (18/18) and in the group that received the triple therapy with pegIFN + RBV + SOF (17/17). The same as in the NEUTRINO study, SVR in genotype 1b was 90% (94/104) with the triple therapy based on pegIFN + RBV + SOF, which was lower than the SVR12 with the GZV/ EBV regimen (99%) (104/105).7,49 The SVR was even lower with the triple therapy of pegIFN + RBV + SOF. In patients with poor outcome factors, it was 89% (87/98) in those with the non-CC IL-28 B genotype, 76% (16/21) in those with cirrhosis of the liver, 50% (7/14) in nonresponders to pegIFN + RBV, and 88% (7/8) in partial responders to treatment.53

Triple therapy with pegIFN + RBV + SOF for 12 weeks is an alternative treatment when interferon-free DAA therapies are not available. It is important to be aware that SVR is lower in patients with genotype 1b and that said response decreases when there are poor outcome factors, such as patients with cirrhosis, or those with a history of prior pegIFN + RBV treatment failure.49,53

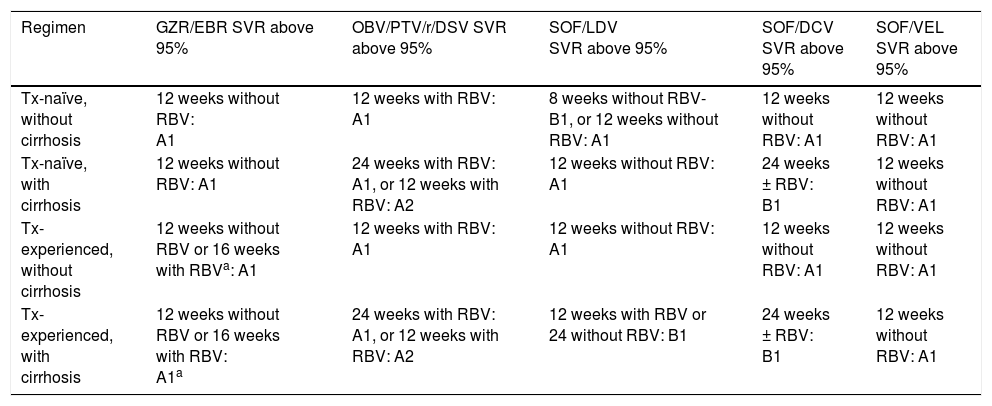

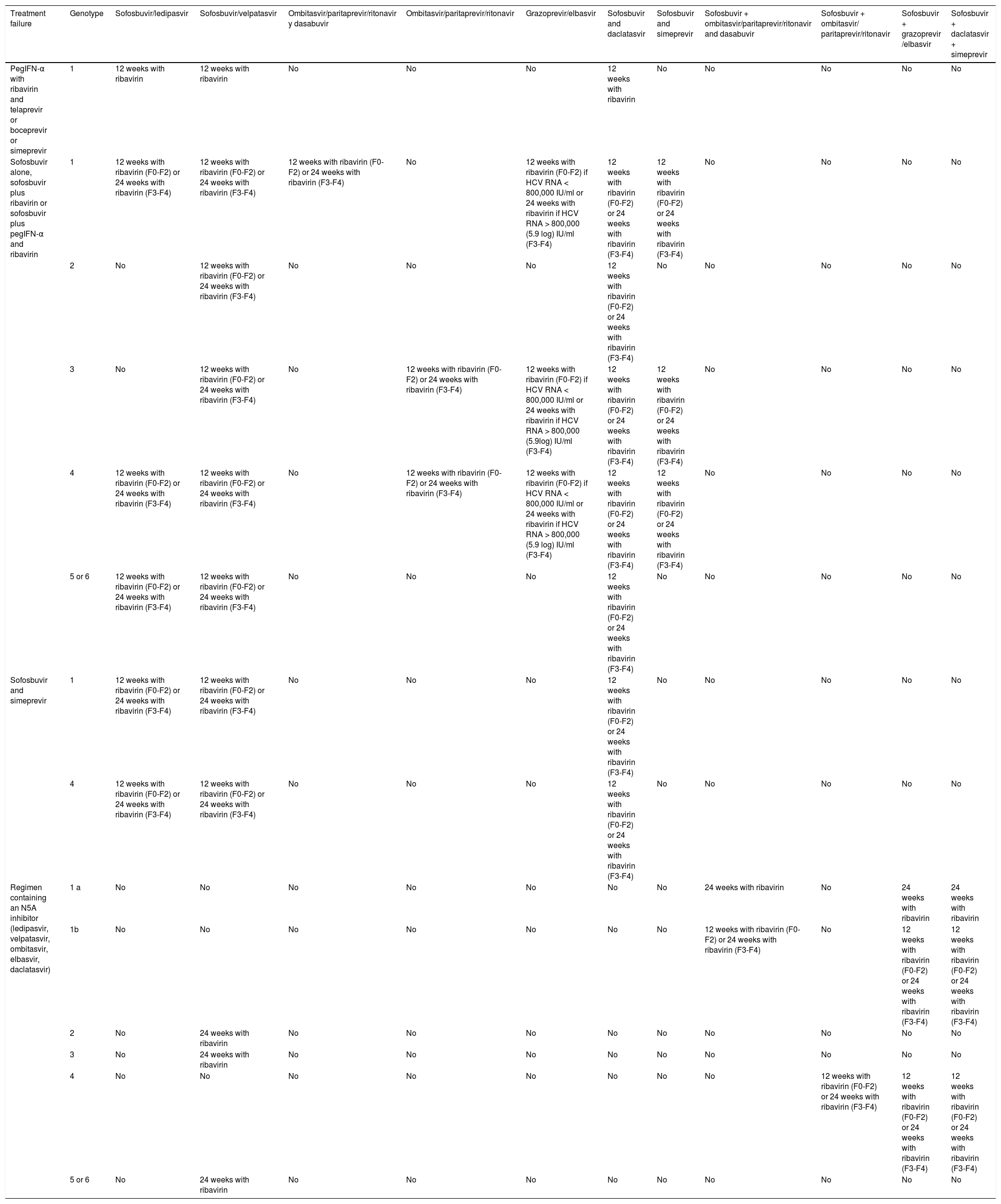

Interferon-free therapies (Tables 2 and 3)In accordance with that suggested by the consensus working group, the medications approved by the National Commission for Protection Against Health Risks (COFEPRIS, Spanish acronym) are listed, along with their level of evidence and strength of recommendation. The medications not yet available in Mexico are listed in the same manner, after the approved available drugs.

Treatment for genotype 1a.

| Regimen | GZR/EBR SVR above 95% | OBV/PTV/r/DSV SVR above 95% | SOF/LDV SVR above 95% | SOF/DCV SVR above 95% | SOF/VEL SVR above 95% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tx-naïve, without cirrhosis | 12 weeks without RBV: A1 | 12 weeks with RBV: A1 | 8 weeks without RBV-B1, or 12 weeks without RBV: A1 | 12 weeks without RBV: A1 | 12 weeks without RBV: A1 |

| Tx-naïve, with cirrhosis | 12 weeks without RBV: A1 | 24 weeks with RBV: A1, or 12 weeks with RBV: A2 | 12 weeks without RBV: A1 | 24 weeks ± RBV: B1 | 12 weeks without RBV: A1 |

| Tx-experienced, without cirrhosis | 12 weeks without RBV or 16 weeks with RBVa: A1 | 12 weeks with RBV: A1 | 12 weeks without RBV: A1 | 12 weeks without RBV: A1 | 12 weeks without RBV: A1 |

| Tx-experienced, with cirrhosis | 12 weeks without RBV or 16 weeks with RBV: A1a | 24 weeks with RBV: A1, or 12 weeks with RBV: A2 | 12 weeks with RBV or 24 without RBV: B1 | 24 weeks ± RBV: B1 | 12 weeks without RBV: A1 |

| Regimen | Asunaprevir + daclatasvir SVR insufficient | Sofosbuvir/simeprevir SVR below 95% |

|---|---|---|

| Tx-naïve, without cirrhosis | Not recommended: A1 | 12 weeks without RBV: A1 |

| Tx-naïve, with cirrhosis | Not recommended: A1 | 24 weeks ± RBVb: B2 |

| Tx-experienced, without cirrhosis | Not recommended: A1 | 12 weeks without RBV: A1 |

| Tx-experienced, with cirrhosis | Not recommended: A1 | 24 weeks ± RBV: B2b |

A1, A2, B1, B2: level of evidence; GZR/EBR: grazoprevir/elbasvir; OBV/PTV/r/DSV: ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir/dasabuvir; RBV: ribavirin; SOF/LDV: sofosbuvir/ledipasvir; SVR: sustained virologic response; Tx: treatment.

12 weeks of treatment without RBV are recommended in patients with previous relapse with pegIFN and ribavirin (PR) and 16 weeks of treatment with ribavirin are recommended in null responders to PR, with or without cirrhosis + AFP (alpha-fetoprotein) under 20 ng/ml, platelets above 90 k, and albumin above 2.5g/dl.

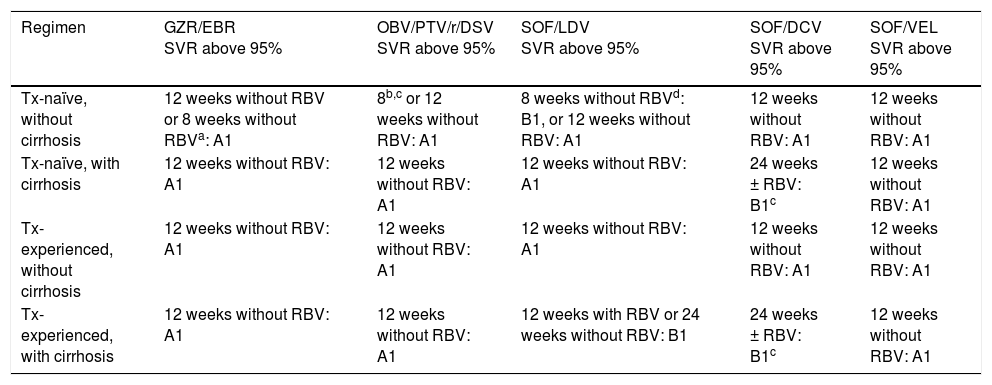

Treatment for genotype 1b.

| Regimen | GZR/EBR SVR above 95% | OBV/PTV/r/DSV SVR above 95% | SOF/LDV SVR above 95% | SOF/DCV SVR above 95% | SOF/VEL SVR above 95% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tx-naïve, without cirrhosis | 12 weeks without RBV or 8 weeks without RBVa: A1 | 8b,c or 12 weeks without RBV: A1 | 8 weeks without RBVd: B1, or 12 weeks without RBV: A1 | 12 weeks without RBV: A1 | 12 weeks without RBV: A1 |

| Tx-naïve, with cirrhosis | 12 weeks without RBV: A1 | 12 weeks without RBV: A1 | 12 weeks without RBV: A1 | 24 weeks ± RBV: B1c | 12 weeks without RBV: A1 |

| Tx-experienced, without cirrhosis | 12 weeks without RBV: A1 | 12 weeks without RBV: A1 | 12 weeks without RBV: A1 | 12 weeks without RBV: A1 | 12 weeks without RBV: A1 |

| Tx-experienced, with cirrhosis | 12 weeks without RBV: A1 | 12 weeks without RBV: A1 | 12 weeks with RBV or 24 weeks without RBV: B1 | 24 weeks ± RBV: B1c | 12 weeks without RBV: A1 |

| Regimen | Asunaprevir+ daclatasvir SVR below 95% | Sofosbuvir/simeprevir SVR below 95% |

|---|---|---|

| Tx-naïve, without cirrhosis | 24 weeks without RBV: A1 | 12 weeks without RBV: A1 |

| Tx-naïve, with cirrhosis | 24 weeks without RBV without NS5A RAVs LK31/Y93: B2 | 24 weeks ± RBV: B2 |

| Tx-experienced, without cirrhosis | Not recommended: A2 | 12 weeks without RBV: A1 |

| Tx-experienced, with cirrhosis | Not recommended: A2 | 24 weeks ± RBV: B2 |

A1, A2, B1: level of evidence; GZR/EBR: grazoprevir/elbasvir; OBV/PTV/r/DSV: ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir/dasabuvir; RBV: ribavirin; SOF/DCV: sofosbuvir/daclatasvir; SOF/LDV: sofosbuvir/ledipasvir; SOF/VEL: sofosbuvir/velpatasvir; SVR: sustained virologic response; Tx: treatment; RAV: resistance-associated variant.

- •

Patients with HCV genotype 1b infection can be treated with a combination of daclatasvir (60mg once-daily) + asunaprevir (100mg twice-daily) for 24 weeks (A1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 88%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 12%

- •

Patients with genotype 1b that are treatment-naïve, do not have cirrhosis or have compensated cirrhosis, and do not have the resistance-associated variants (RAVs), NS5A-L31 and NS5A-Y93, should receive a 24-week regimen (B2).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 92%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 8%.

- •

Patients with genotype 1b that are treatment-experienced, have cirrhosis, or are IFN-intolerant (depression, anemia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia) are not considered good candidates for that regimen (A2).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 100%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 0%.

- •

Treatment failure with that regimen can lead to a risk for developing variants that are resistant to rescue therapy (C1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 90%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 10%.

The daclatasvir (60mg once-daily) plus asunaprevir (100mg twice-daily) regimen for 24 weeks is a treatment option in patients with chronic hepatitis infected with genotype 1b. The HALLMARK-DUAL study included treatment-naïve patients infected with genotype 1b, nonresponders to prior treatment with pegIFN/RBV, as well as patients that were ineligible for or did not tolerate pegIFN, which included patients with depression, anemia < 8.5mg/dl, neutropenia < 1.5 cells/l, or F3/F4 fibrosis with thrombocytopenia < 90,000 platelets. The SVR12 reported in treatment-naïve patients was 91% (182/293), 82% (168/205) in the patients that were nonresponders to prior treatment, and 83% (192/235) in the patients with pegIFN intolerance. SVR12 in the patients with cirrhosis was: 91% (29/32) in the treatment-naïve patients, 87% (55/63) in the nonresponders, and 79% (88/111) in the patients that are ineligible for or intolerant to pegIFN.54

Twenty-seven of the 596 patients (5%) presented with the NS5A-L31 polymorphism, and of those patients, only 41% achieved SVR12. Likewise, 48 patients (8%) (48/596) had the NS5A-Y93 polymorphism, of which only 38% (18 patients) achieved SVR12.

SVR12 was achieved in 39% (29/75) of the patients that had the NS5A L31 and Y93 polymorphisms, compared with the 92% SVR12 in the patients without the RAVs (478/521).54

The AI447-026 study included treatment-naïve patients with genotype 1b infection that were ineligible for or had intolerance to IFN and those that were nonresponders to previous treatment. SVR12 was 88% (119/135) in the treatment-naïve IFN-ineligible or intolerant patients and 80.5% (70/87) in the nonresponders to prior treatment.55

In an analysis of several clinical trials with DCV/ASV for 24 weeks, SVR12 was evaluated in patients with genotype 1b with and without cirrhosis. Treatment-naïve patients, patients that were IFN-ineligible or intolerant, and patients that were nonresponders were included. The general SVR12 in patients with cirrhosis was 84% (192/228). It was 91% (29/32) in the treatment-naïve group with cirrhosis, 80% (98/122) in the IFN-ineligible or intolerant group, and 88% (65/74) in the nonresponders to prior treatment.

The SVR12 results in the patients that did not have cirrhosis were: a general SVR12 of 85% (539/637), 89% (152/171) in the treatment-naïve patients, 86% (213/248) in patients that were ineligible for or intolerant to IFN, and 79% (173/218) in the nonresponders.56

SVR12 in the patients with cirrhosis that were IFN-intolerant due to depression and thrombocytopenia associated with advanced fibrosis was 73% (11/15) and 76% (53/70), respectively. SVR12 in the patients with anemia and neutropenia that were ineligible for IFN was 92% (24/26).56

RecommendationsGrazoprevir/elbasvir- •

Patients with HCV genotype 1 infection can be treated with the fixed-dose combination of grazoprevir (100mg) and elbasvir (50mg) in one tablet administered once-daily (A1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 88%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 12%.

- •

Patients with genotype 1b that are treatment-naïve or treatment-experienced and that do not have cirrhosis or have compensated cirrhosis, should be treated with the 12-week regimen (A1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 100%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 0%.

- •

Patients with genotype 1a that are treatment-naïve or treatment-experienced, that do not have cirrhosis or have compensated cirrhosis, and in whom there is no possibility of NS5A RAV testing, should receive the 12-week treatment regimen, if their HCV RNA < 800,000 IU/ml. If their HCV RNA ≥ 800,000 IU/mL, then treatment should be the 16-week regimen + ribavirin (B1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 100%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 0%.

- •

Patients with genotype 1a that are treatment-naïve or treatment-experienced, that do not have cirrhosis or have compensated cirrhosis, that have the NS5A RAVs, and their HCV RNA ≥ 800,000 IU/ml should be treated with the 16-week regimen + ribavirin (B1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 100%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 0%.

Recommendations for treatment with the fixed-dose combination of grazoprevir (100mg) / elbasvir (50mg) for 12 weeks without ribavirin in patients with genotype 1a or 1b, with or without previous treatment, with no cirrhosis or with compensated cirrhosis, are based on the results of the C-EDGE-TN and C-EDGE-TE phase III studies. In the C-EDGE-TN study, the SVR12 was 92% (144/157) and 99% (129/131) in genotype 1a and 1b, respectively. The presence of cirrhosis did not affect the efficacy of that treatment regimen.42

In the C-EDGE-TE study that included treatment-experienced patients, 34% of whom presented with compensated cirrhosis, the SVR12 in patients with genotype 1a and those with genotype 1b was 92% (55/60) and 100% (34/34), respectively, with the combination treatment of GZV/EBV for 12 weeks without RBV and 93% (56/60) and 97% (28/29), respectively, after 12 weeks with RBV. When treatment was extended to 16 weeks, the SVR12 in the patients with genotype 1a was 100% (55/55) and 94% (45/48), with and without RBV, respectively, and was 100% (37/37) and 98% (46/47), with and without RBV, respectively, in the patients with genotype 1b.57

In an integrated response predictor analysis of phase II and phase III studies on a total of 1,408 patients with genotype 1a that received GZV/EBV for 12 weeks ± RBV, the only variables associated with a lower SVR12 rate in patients with or without previous treatment, and without cirrhosis or with compensated cirrhosis, were the baseline levels of HCV RNA ≥ 800,000 IU/ml and the presence of NS5A RAVs.

Therefore, we recommend that NS5A RAV testing be carried out on all patients with an HCV RNA load > 800,000 IU/ml. In patients with NS5A RAVs or in those in whom the presence of NS5A RAVs cannot be determined, the fixed-dose combination of GZV/EBV for 16 weeks with RBV is recommended.57,58

RecommendationsOmbitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir plus dasabuvir- •

Patients with HCV genotype 1 infection can be treated with an IFN-free regimen with the fixed-dose combination of ombitasvir (12.5mg), paritaprevir (75mg), and ritonavir (50mg) in a single tablet (taken once-daily with food) plus dasabuvir (250mg) (one tablet twice-daily) (A1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 100%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 0%.

- •

Patients with genotype 1b that do not have cirrhosis or have compensated cirrhosis should receive a regimen of ombitasvir, paritaprevir, and ritonavir plus dasabuvir for 12 weeks with no ribavirin (A1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 83%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 17%.

- •

Patients with genotype 1a that do not have cirrhosis should receive that combination daily for 12 weeks with a body weight-adjusted dose of ribavirin (1,000 or 1,200mg in patients < 75kg or ≥ 75kg, respectively) (A1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 100%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 0%.

- •

In patients with genotype 1a that have compensated cirrhosis, that combination for 24 weeks with a daily weight-based dose of ribavirin (1,000 or 1,200mg in patients < 75kg or ≥ 75kg, respectively) is recommended (A1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 100%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 0%.

- •

The regimen can be shortened to 12 weeks in patients with genotype 1a that are treatment-naïve or treatment-experienced, that have compensated cirrhosis, and that present with pre-treatment levels of three baseline response predictors: alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) < 20 ng/ml, platelets ≥ 90 x 109/l, and albumin ≥ 3.5g/dl (A2).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 100%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 0%.

The indication for the ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir (25/150/100mg once-daily) plus dasabuvir (250mg twice-daily) (OBV/PTV/r/DSV) regimen used in patients with genotype 1 is based on numerous clinical trials. It is contraindicated in patients with decompensated cirrhosis of the liver.

In the SAPPHIRE I study, treatment-naïve patients with no cirrhosis received that regimen plus RBV for 12 weeks. The patients with genotype 1a achieved 95% SVR12 (307/322) and those with genotype 1b reached 98% (148/151).59 The use of that regimen with RBV was evaluated in the PEARL IV study in patients with genotype 1a with no previous treatment and no cirrhosis, resulting in 90% SVR12 (185/205) without RBV and 97% (97/100) with RBV. The PEARL III study showed that patients with genotype 1b with no previous treatment and no cirrhosis that received OBV/PTV/r/DSV with or without RBV, achieved 99% SVR12 (207/209) without RBV and 99% (209/201) with RBV.60

The results of the MALACHITE-I study were 97% SVR12 (67/69) in patients with genotype 1a with no previous treatment and no cirrhosis, treated with that regimen plus RBV for 12 weeks. and 98% SVR12 (81/83) in patients with genotype 1b, treated without RBV for 12 weeks.61

The GARNET study provided recent evidence showing that patients with genotype 1b with no cirrhosis and a METAVIR F0 to F3 fibrosis grade, treated with OBV/PTV/r/DSV without RBV for 8 weeks, achieved 97% SVR12 (161/166). Of the 15 patients with F3 in that study, 13 achieved SVR12. Thus, shortening treatment without RBV to 8 weeks can be considered in treatment-naïve patients with genotype 1b and a F0 to F2 grade of fibrosis.62

In the SAPPHIRE II study, patients that did not present with cirrhosis and were nonresponders to previous treatment with pegIFN + RBV were treated with OBV/PTV/r/DSV plus RBV. The patients with genotype 1a achieved an SVR12 rate of 96% (166/173), and in those with genotype 1b, SVR12 was 97% (119/123). The SVR12 according to the type of response to the previous treatment was 95% (139/146) in the nonresponders, 95% (82/86) in patients with relapse, and 100% (65/65) in the partial responders.63

In the PEARL II study, patients with genotype 1b with no cirrhosis that did not respond to previous treatment with pegIFN and RBV achieved 100% SVR12 (91/91) without RBV and 97% (85/88) with RBV.64

In the MALACHITE II study on patients with no cirrhosis and with genotype 1a or 1b that were nonresponders to previous treatment, there was 99% SVR12 (100/101) with OBV/PTV/r/DSV plus RBV.61

Treatment-naïve patients and patients with compensated cirrhosis that did not respond to pegIFN and RBV were treated in the TURQUIOSE II study with the OBV/PTV/r/DSV plus RBV regimen for 12 or 24 weeks. Patients that received the 12-week regimen had 92% SVR12 (191/208) and those with the 24-week treatment had 96% (165/172). According to genotype, the patients with genotype 1a had 92% SVR12 (239/261) and those with genotype 1b had 99% (118/119).65

In a sub-analysis of the TURQUIOSE II study, the possibility of shortening treatment to 12 weeks was described in patients with genotype 1a and compensated cirrhosis that presented with the following factors: AFP below 20 ng/ml, platelets above 90 x 109/l, and albumin above 3.5g/dl.65

The TURQUOISE III study reported 100% SVR12 (60/60) with a 12-week regimen with no RBV in patients with genotype 1b, with or without previous treatment, and with compensated cirrhosis.66

RecommendationsSofosbuvir/daclatasvir- •

Patients with HCV genotype 1 infection can be treated with an IFN-free combination of sofosbuvir (400mg) and daclatasvir (60mg), daily (A1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 91%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 9%.

- •

Patients with genotype 1a or genotype 1b infection, that are treatment-naïve or treatment-experienced, and that do not have cirrhosis should be treated with the 12-week regimen (A1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 100%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 0%.

- •

Patients with genotype 1a or genotype 1b infection, that are treatment-naïve or treatment-experienced, and that have cirrhosis should be treated with the 24-week regimen ± ribavirin (B1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 100%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 0%.

The daily-dose combination treatment of daclatasvir (60mg) and sofosbuvir (400mg) can be recommended, based on the ALLY-2 phase IIb study and the ALLY-1 phase III study. In the phase IIb study, utilizing the DCV/SOF combination in patients with no cirrhosis, the following results were obtained: in treatment-naïve patients with 24 weeks of DCV/SOF ± RBV combination therapy, 100% SVR12 (14/14) was achieved in patients with no RBV and 100% (15/15) in patients with RBV. In patients that did not respond to previous treatment with pegIFN + RBV + telaprevir or boceprevir, SVR was 100% (21/21) with 24 weeks of treatment with daclatasvir/sofosbuvir with no ribavirin and 95% (20/21) with ribavirin. In the third arm of that study, SVR12 was 100% (40/40) in treatment-naïve patients after 12-week treatment with DCV/SOF and no RBV.67

In the ALLY-2 phase III study, the DCV/SOF combination was administered for 12 weeks in patients with genotypes 1-4 coinfected with HIV. Of that cohort, 123 patients had genotype 1 infection, 83 of whom were treatment-naïve. Patients with and without previous treatment achieved 98% SVR12 (43/44) and 96% (80/83), respectively. Of those patients, 104 with genotype 1a had 96% SVR12 (100/104) and 23 with genotype 1b had 100% SVR12 (23/23).12

In the ALLY-1 phase III study, in 45 patients with genotype 1 and advanced cirrhosis, 34 had genotype 1a infection and 11 had genotype 1b. Treatment with DCV/SOF + RBV (initial dose of 600mg, later titrated) was administered for 12 weeks. The patients with genotype 1a achieved 76% SVR12 (26/34), whereas those with genotype 1b achieved 100% SVR12 (11/11).68

Because the patients with compensated cirrhosis were not adequately represented in any of the 3 studies mentioned above, treatment duration was not clearly determined. In an analysis of a patient cohort from a European compassionate use program, it is suggested that treatment should be prolonged to 24 weeks with or without RBV in patients with compensated cirrhosis.69

RecommendationsSofosbuvir/Ledipasvir- •

Patients with HCV genotype 1 infection can be treated with the combination of sofosbuvir (400mg) and ledipasvir (90mg) in a single tablet once-daily (A1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 86%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 14%.

- •

In patients with genotype 1a or 1b that are treatment-naïve, do not have cirrhosis, or have compensated cirrhosis, the fixed-dose combination of one tablet of sofosbuvir/ledipasvir daily with no ribavirin for 12 weeks is recommended (A1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 100%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 0%.

- •

In patients with genotype 1a or 1b that are treatment-experienced and do not have cirrhosis, the fixed-dose combination of one tablet of sofosbuvir/ ledipasvir daily with no ribavirin for 12 weeks is recommended (A1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 100%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 0%.

- •

In patients with genotype 1a or 1b that are treatment-experienced and have compensated cirrhosis, the fixed-dose combination of one tablet of sofosbuvir/ledipasvir daily with ribavirin for 12 weeks (A1) or for 24 weeks with no RBV is recommended (B1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 100%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 0%.

- •

In treatment-naïve patients with genotype 1a or 1b that do not have cirrhosis, in whom an F0-F2 grade of fibrosis is determined through a reliable invasive or noninvasive study, and whose HCV RNA level is < 6,000,000 IU/ml (6.8 log), the fixed-dose combination of a single tablet of sofosbuvir/ledipasvir daily can be reduced to 8 weeks, with no ribavirin (B1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 91%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 9%.

The phase III ION-1, ION-2, and ION-3 studies showed that the combination of sofosbuvir and ledipasvir is safe and effective for the treatment of patients with genotype 1a or 1b HCV infection, with or without cirrhosis, with compensated or decompensated cirrhosis, and with or without a history of previous treatment.70–72 The ION-1 study included patients with no history of previous treatment and only 16% with compensated cirrhosis. In the ION-1, SVR12 was 99% (211/214) with 12 weeks of treatment without ribavirin and 97% (211/217) with 12 weeks of treatment with ribavirin. Response at 24 weeks with the same treatment regimen was 99% (215/217) with RBV and 98% (212/217) without RBV.70

In the ION-3 study, patients with no history of previous treatment, with no cirrhosis, and with an F0-F2 grade of fibrosis achieved 94% SVR12 (201/215) with 8 weeks of the combination treatment with no RBV, 93% (201/216) with 8 weeks with RBV, and 95% (205/216) with 12 weeks with no RBV. Even though the differences in SVR in the three groups were not statistically significant, the absolute number of relapses after treatment completion was higher in the patients treated for 8 weeks.72 A secondary analysis indicated that only patients with an HCV RNA level < 6 million U/l (6.8 log) could be treated for 8 weeks. The relapse rate in patients treated for 8 weeks was lower in women than in men. The relapse rate was 1% (1/84) and 1% (1/96) in women treated with SOF/LDV with and without RBV, respectively, and 8% (10/129) and 7% (8/114) in men treated with the same regimen with and without ribavirin.72 The results of the ION-3 study were confirmed in real-world studies in Europe and the United States that included 4 different groups of patients with 95 to 99% SVR12 rates.73

Patients previously treated with pegIFN + RBV or pegIFN + RBV plus telaprevir or boceprevir, and 20% of whom had cirrhosis, were included in the ION-2 study. SVR12 was 94% (102/109) with 12 weeks with no RBV and 96% (107/111) with 12 weeks with RBV. However, SVR improved to 99% in the two groups with 24 weeks of treatment with or without RBV.74

An analysis of 513 patients with genotype 1 infection with compensated cirrhosis treated with the combination of SOF/LDV, with or without RBV, that were included in different phase II and phase III studies, showed 95% SVR12 (305/322) with 12 weeks of treatment and 98% (188/191) with 24 weeks. In that study, neither duration (12 or 24 weeks) nor RBV administration impacted SVR in treatment-naïve patients. However, in treatment-experienced patients, SVR12 was 90% with 12 weeks of treatment with no RBV, 96% with 12 weeks with RBV, 98% with 24 weeks with no RBV, and 100% with 24 weeks with RBV.75 In the SIRIUS study that included patients with compensated cirrhosis and previous treatment failure with the triple-regimen of pegIFN + RBV + telaprevir or boceprevir, SVR12 was 96% (74/77) with the combination for 24 weeks with RBV and 97% (75/77) with the combination with no RBV.76

RecommendationsSofosbuvir / simeprevir- •

Patients with HCV genotype 1 infection that do not have cirrhosis can be treated with an IFN-free combination of sofosbuvir (400mg/24h) and simeprevir (150mg/24h), one tablet of each every 24h for 12 weeks (A1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 95%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 5%.

- •

Patients with genotype 1a and 1b that are treatment-naïve or treatment-experienced, do not have cirrhosis, and have or do not have the Q80K polymorphism should receive that regimen for 12 weeks (A1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 96%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 4%.

- •

Patients with genotype 1a that are treatment-naïve or treatment-experienced, have compensated cirrhosis, and do not have the Q80K polymorphism should receive that regimen for 24 weeks ± ribavirin (B2).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 100%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 0%.

- •

Treatment-experienced patients with genotype 1b that have compensated cirrhosis should receive that regimen for 24 weeks ± ribavirin (B2).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 100%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 0%.

The combination of simeprevir (150mg) and sofosbuvir (400mg) for the treatment of patients with genotype 1 HCV infection was evaluated in the OPTIMIST-1 and OPTIMIST-2 studies. A total of 310 patients were included in the OPTIMIST-1 study. They did not present with cirrhosis and were either treatment-naïve or treatment-experienced. They randomly received treatment with sofosbuvir and simeprevir for 12 weeks or 8 weeks. SVR was 97% (150/155) with 12 weeks of treatment and 83% (128/155) with 8 weeks of treatment. SVR was similar in the patients with or without a history of previous treatment that received 12 weeks of simeprevir + sofosbuvir. There was also no difference in SVR in the patients with genotype 1a with the presence of the Q80K mutation.77

The combination of simeprevir and sofosbuvir in patients with cirrhosis, with or without previous treatment, was assessed in the OPTIMIST-2 study. A total of 103 patients were treated for 12 weeks with a daily dose of 150mg of simeprevir and 400mg of sofosbuvir. Treatment-naïve patients achieved 88% SVR (44/50) and treatment-experienced patients achieved 79% (42/53). SVR was similar in patients with genotype 1a and those with genotype 1b, with no presence of Q80K mutation, at 84% (26/31) and 92% (35/38), respectively. Due to the low response rates in the patients with previous treatment failure, extending that combination treatment to 24 weeks, with or without ribavirin, is recommended. Patients with genotype 1a with cirrhosis and the presence of the Q80K mutation are not considered candidates for receiving the simeprevir/sofosbuvir combination.15,78

RecommendationsSofosbuvir / velpatasvir- •

Patients with HCV genotype 1 infection can be treated with a fixed-dose combination of sofosbuvir (400mg) and velpatasvir (100mg) in one tablet administered once-daily (A1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 100%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 0%.

- •

That treatment without ribavirin is recommended for 12 weeks in patients with genotype 1a infection or genotype 1b infection, with or without previous treatment, and with compensated cirrhosis (A1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 100%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 0%.

Those recommendations are based on the results of the phase III ASTRAL-1 study, in which patients with genotype 1 HCV infection (22% with cirrhosis, 66% treatment-naïve, 34% treatment-experienced, 44% that had been exposed to direct-acting antivirals) were studied. Those patients were treated with a fixed-dose combination of SOF/VEL for 12 weeks with no RBV.79 SVR12 was 98% (323/328) in the total patient group, 98% (206/210) in the patients with genotype 1a infection, and 99% (117/118) in those with genotype 1b infection.

In the ASTRAL-5 study, patients with HIV infection treated with the same regimen and infected with genotype 1a achieved 95% SVR (62/65) and those with genotype 1b had 92% SVR (11/12). SVRs were 100% (19/19) and 94% (80/85) in patients with or without cirrhosis, and 93% (71/75) and 97% (28/29) in treatment-naïve and treatment-experienced patients, respectively.80

Genotype 2 infectionThere are different treatment options for patients with genotype 2 infection, two of which are first-line: the combination of sofosbuvir and velpatasvir (a combination not yet available in Mexico) and the combination of sofosbuvir and daclatasvir.9,46 Other treatment options can be evaluated with the following evidence:

RecommendationInterferon therapies- •

Patients with compensated cirrhosis and/or treatment-experienced patients can be treated with the combination of weekly pegIFN-α plus a daily weight-based dose of ribavirin (1,000 or 1,200mg in patients < 75kg or ≥ 75kg, respectively) plus sofosbuvir (400mg) for 12 weeks (B1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 87%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 13%.

In patients with previous treatment failure, particularly those with cirrhosis, the inclusion of treatment with pegIFN has been evaluated. The LONESTAR-2 study assessed the combination of pegIFN 180μg weekly, sofosbuvir 400mg/daily, and ribavirin by kilogram of weight divided into 2 doses for 12 weeks. Cirrhosis was present in 61% of the patients and SVR at 12 weeks was 96%.81

Recommendations (see Table 4)Sofosbuvir and daclatasvir- •

Treatment-naïve patients and with no cirrhosis can be treated with the combination of sofosbuvir (400mg) plus daclatasvir (60mg) daily for 12 weeks (B1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 100%.

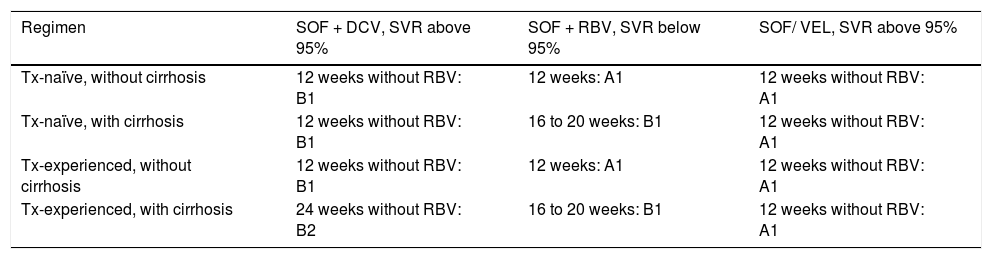

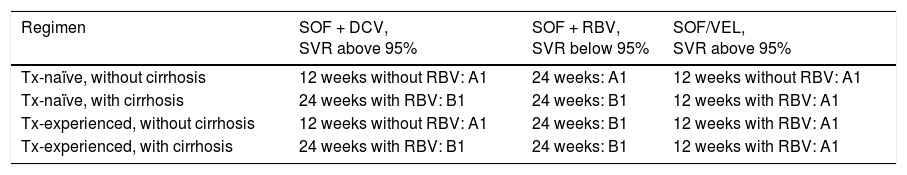

Treatment for genotype 2.

| Regimen | SOF + DCV, SVR above 95% | SOF + RBV, SVR below 95% | SOF/ VEL, SVR above 95% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tx-naïve, without cirrhosis | 12 weeks without RBV: B1 | 12 weeks: A1 | 12 weeks without RBV: A1 |

| Tx-naïve, with cirrhosis | 12 weeks without RBV: B1 | 16 to 20 weeks: B1 | 12 weeks without RBV: A1 |

| Tx-experienced, without cirrhosis | 12 weeks without RBV: B1 | 12 weeks: A1 | 12 weeks without RBV: A1 |

| Tx-experienced, with cirrhosis | 24 weeks without RBV: B2 | 16 to 20 weeks: B1 | 12 weeks without RBV: A1 |

A1, B1, B2: level of evidence; SOF/DCV: sofosbuvir/daclatasvir; SOF/RBV: sofosbuvir/ribavirin; SOF/VEL: sofosbuvir/velpatasvir; SVR: sustained virologic response; Tx: treatment;

In agreement with minor reservations: 0%.

The data from in vitro action of daclatasvir against HCV has been confirmed in clinical practice. The combination of 60mg of daclatasvir plus 400mg of sofosbuvir for 12 weeks demonstrated its efficacy, achieving eradication of the virus in treatment-naïve patients with genotype 2 infection, with a response of 98% upon treatment completion.67

Recommendation- •

Treatment-naïve patients with no cirrhosis or with compensated cirrhosis should receive the combination of sofosbuvir (400mg) plus daclatasvir (60mg) for 12 weeks (B2).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 96%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 4%.

Extending the 12-week combination treatment of daclatasvir plus sofosbuvir in treatment-naïve patients with compensated cirrhosis to 24 weeks has been associated with 100% SVR.67

RecommendationsSofosbuvir and ribavirin- •

The combination of sofosbuvir 400mg plus body-weight based ribavirin (1,000 or 1,200mg in patients < 75kg or ≥ 75kg, respectively) can be used for a period of 12 weeks (A1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 91%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 9%.

Sofosbuvir 400mg daily combined with body weight-adjusted ribavirin in treatment-naïve patients with genotype 2 infection is supported by the FISSION, POSITRON, and VALANCE studies. In the FISSION study, patients were randomized to receive pegIFN and ribavirin 800mg daily for 24 weeks or sofosbuvir 400mg and weight-adjusted ribavirin for 12 weeks.49 Patients under treatment with sofosbuvir and ribavirin had 97% SVR vs 78% SVR in patients under treatment with pegIFN and ribavirin. Combining the results of the 3 studies, the SVR rate was 94%.82–84

Recommendations- •

Therapy should be extended from 16 to 24 weeks in patients with cirrhosis, especially if they are treatment-experienced (B1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 100%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 0%.

There are no data determining the extension of therapy that impacts SVR in patients with compensated cirrhosis, with or without previous treatment. Even though experience comes from a reduced number of patients enrolled in clinical studies on patients with cirrhosis infected with genotype 2, the data and results are in favor of extending therapy from 12 to 16 weeks.83,85

The FUSION study reported SVR above 60 to 78% when therapy was extended from 12 to 16 weeks.83 In contrast, the BALANCE study reported a higher SVR rate in patients treated only for 12 weeks (88%).84

RecommendationSofosbuvir and velpatasvir- •

Patients with HCV genotype 2 infection can be treated with a fixed-dose combination of sofosbuvir (400mg) and velpatasvir (100mg) in one tablet, administered once-daily (A1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 100%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 0%.

That therapeutic option is based on the results of the ASTRAL-2 phase III study on patients with genotype 2 infection. Eighty-six percent of the patients evaluated were treatment-naïve and 14% had compensated cirrhosis, 14% of whom were treatment-experienced. SVR of 99% was achieved upon completion of the 12 weeks of treatment (133 of the 134 patients included), thus confirming the effectiveness of said treatment in patients with no cirrhosis, with or without previous treatment, as well as in patients with compensated cirrhosis, with or without previous treatment.86

Recommendation- •

Treatment-naïve or treatment-experienced patients with no cirrhosis or with compensated cirrhosis can be treated with a fixed-dose combination of sofosbuvir and velpatasvir for 12 weeks with no ribavirin (A1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 100%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 0%.

In the ASTRAL 2 study, the 12-week regimens of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir vs sofosbuvir and ribavirin were compared, resulting in SVR of 99% vs 94%. The ASTRAL 1 study evaluated 104 treatment-naïve patients, with or without cirrhosis, observing 100% SVR.79,86

Treatment of genotype 3-6 HCVGenotype 3 infectionRecommendationsInterferon therapies- •

Patients with HCV genotype 3 infection can be treated with the combination of weekly pegIFN-α plus a daily weight-based dose of ribavirin (1,000 or 1,200mg in patients < 75kg or 75kg, respectively) plus daily sofosbuvir (400mg) for 12 weeks (B1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 100%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 0%.

- •

That combination is a useful alternative in patients that did not previously reach SVR with the combination of sofosbuvir plus ribavirin (B1).

Level of agreement: in complete agreement 92%.

In agreement with minor reservations: 8%.

In a randomized, multicenter, phase II clinical trial by Lawitz et al.87 that included 212 treatment-naïve patients with genotype 1, 2, or 3 HCV, they evaluated the efficacy and tolerability of sofosbuvir 200mg (n = 48), sofosbuvir 400mg (n = 48), or placebo (n = 26) in combination with pegIFN (180μg per week) and weight-adjusted RBV, respectively. There was SVR at 12 weeks in 43/48 patients (90%) from the group that received sofosbuvir 200mg, in 43/47 (91%) from the group that received sofosbuvir 400mg, and in 15/26 (58%) from the placebo group.

The results of a randomized, multicenter, phase III clinical trial that evaluated the efficacy and safety of sofosbuvir and RBV, with or without pegIFN-α in patients with genotype 3 HCV, with or without previous treatment, showed an SVR rate at 12 weeks of 71% and of 84% in the patients that received 16 and 24 weeks of sofosbuvir and RBV, respectively. SVR was significantly higher (93%) in the patients that received the triple therapy with sofosbuvir, pegIFN, and RBV.85

For treatment-naïve patients with no cirrhosis, that combination has shown up to 92% effectiveness, according to the study by Lawitz, but only 10 patients with genotype 3 infection were included in that cohort.87

In an open and nonrandomized clinical trial by Lawitz et al.88 on patients with cirrhosis of the liver, 24 patients with genotype 3 were included. All of them had previous treatment failure and half had cirrhosis. The efficacy and safety of SOF + pegIFN + RBV was measured for 12 weeks. SVR12 in the group with genotype 3 was 83%, with no significant difference between patients with or without cirrhosis of the liver.