There are no studies on the factors associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) relapse in primary care patients.

AimTo identify the risk factors associated with GERD relapse in primary care patients that responded adequately to short-term treatment with a proton pump inhibitor.

Patients and methodsA cohort study was conducted that included GERD incident cases. The patients received treatment with omeprazole for 4 weeks. The ReQuest questionnaire and a risk factor questionnaire were applied. The therapeutic success rate and relapse rate were determined at 4 and 12 weeks after treatment suspension. A logistic regression analysis of the possible risk factors for GERD relapse was carried out.

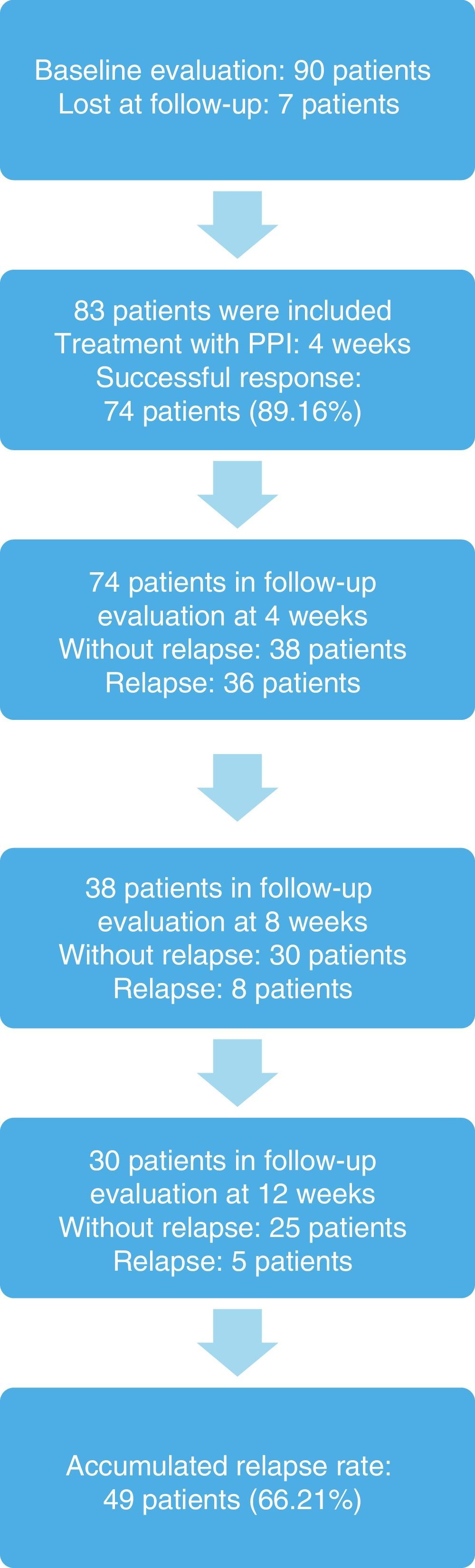

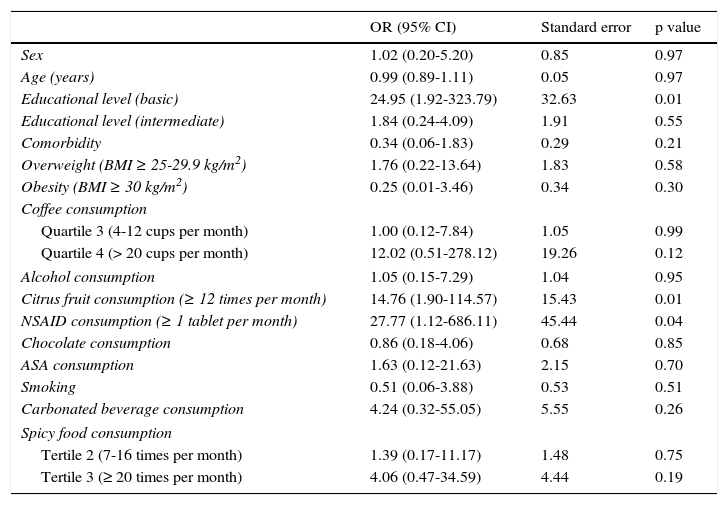

ResultsOf the 83 patient total, 74 (89.16%) responded to treatment. Symptoms recurred in 36 patients (48.64%) at 4 weeks and in 13 patients (17.57%) at 12 weeks, with an overall relapse rate of 66.21%. The OR multivariate analysis (95% CI) showed the increases in the possibility of GERD relapse for the following factors at 12 weeks after treatment suspension: basic educational level or lower, 24.95 (1.92-323.79); overweight, 1.76 (0.22-13.64); obesity, 0.25 (0.01-3.46); smoking, 0.51 (0.06-3.88); and the consumption of 4-12 cups of coffee per month, 1.00 (0.12-7.84); citrus fruits, 14.76 (1.90-114.57); NSAIDs, 27.77 (1.12-686.11); chocolate, 0.86 (0.18-4.06); ASA 1.63 (0.12-21.63); carbonated beverages, 4.24 (0.32-55.05); spicy food 7-16 times/month, 1.39 (0.17-11.17); and spicy food ≥ 20 times/month, 4.06 (0.47-34.59).

ConclusionsThe relapse rate after short-term treatment with omeprazole was high. The consumption of citrus fruits and NSAIDs increased the possibility of GERD relapse.

No existen estudios en primer nivel de atención sobre factores asociados a recaída de enfermedad por reflujo gastroesofágico (ERGE).

ObjetivoIdentificar factores de riesgo asociados a recaída de ERGE en pacientes de primer nivel de atención que respondieron adecuadamente a un tratamiento corto con inhibidor de la bomba de protones.

Pacientes y métodosEstudio de cohorte, se incluyeron casos incidentes de ERGE. Se dio tratamiento con omeprazol durante 4 semanas. Se aplicó ReQuest y un cuestionario de factores de riesgo. Se determinó la tasa de éxito terapéutico y de recaída a las 4 y 12 semanas después de suspender el tratamiento. Se realizó análisis de regresión logística de los posibles factores de riesgo para recaída de ERGE.

ResultadosDe 83 pacientes, 74 (89.16%) respondieron al tratamiento. Los síntomas recurrieron en 36 pacientes (48.64%) a las 4 semanas y en 13 pacientes (17.57%) a las 12 semanas; recaída acumulada: 66.21%. En el análisis multivariado RM (intervalo de confianza del 95%): escolaridad básica o menor 24.95 (1.92-323.79), sobrepeso 1.76 (0.22-13.64), obesidad 0.25 (0.01-3.46), consumo de 4-12 tazas de café al mes 1.00 (0.12-7.84), cítricos 14.76 (1.90-114.57), AINE 27.77 (1.12-686.11), chocolate 0.86 (0.18-4.06), ácido acetilsalicílico 1.63 (0.12-21.63), tabaquismo 0.51 (0.06-3.88), bebidas carbonatadas 4.24 (0.32-55.05), picante de 7-16 veces/mes 1.39 (0.17-11.17), picante ≥ 20 veces/mes, 4.06 (0.47-34.59) de recaída de ERGE a las 12 semanas de suspender tratamiento.

ConclusionesLa tasa de recaída posterior al tratamiento corto con omeprazoI fue alta. El consumo de cítricos y el consumo de AINE incrementaron la posibilidad de recaída de ERGE.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is defined as the ascent of the gastric content that causes symptoms or structural damage of the esophageal mucosa. The characteristic symptoms are heartburn and regurgitation. Affected individuals can also present with extraesophageal manifestations.1

GERD is a frequent illness. When heartburn or acid regurgitation is the dominant symptom, sensitivity and specificity are high enough to make the diagnosis. Empirical treatment of GERD with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) has been accepted due to their high success rate of 80 to 92%.2,3

A GERD relapse rate after treatment with PPIs has been described to vary from 11 to 44%. There is evidence that lifestyle is associated with GERD symptoms. However, there is little evidence to support the efficacy of lifestyle modifications in reducing GERD symptoms and there are no studies conducted on primary care patients for identifying the risk factors associated with relapse in patients successfully treated with PPIs.4–11

The aim of this study was to identify the factors associated with GERD relapse in primary care patients that responded adequately to short-term treatment with a PPI.

Patients and methodsA cohort study was conducted at the Unidad de Medicina Familiar número 2 (UMF 2) of the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social (IMSS), Puebla, which is the primary care unit for the urban area. It has 23 consultation offices, 46 family physicians, and insures a population of 114,000 individuals. GERD incident cases were identified within the time frame of August 1, 2009 to April 30, 2010. They included adults between 18 and 49 years of age that had not received treatment for GERD, that agreed to participate in the study, and that had a score ≥ 4 on the Carlsson-Dent questionnaire (CDQ), which was validated in Spanish on Mexicans to evaluate symptoms and triggering factors associated with GERD.12 Patients with prior use of PPIs, prokinetics or antacids, and patients that were pregnant or had alarm symptoms (weight loss, dysphagia, hematemesis, melena, persistent vomiting, or abdominal tumor) were excluded from the study. Those patients that did not wish to continue participating in the study or that abandoned the follow-up were eliminated. The study focused on primary care, and therefore patients 50 years of age or older were not included because, according to clinical practice guidelines, those patients require a more extensive evaluation that includes endoscopic examination.11,13

The medical history was taken of the patients that met the selection criteria and their body mass index (BMI) was identified. They also answered a lifestyle questionnaire that included possible GERD risk factors described in the literature, such as the consumption of coffee, alcohol, citrus fruits, chocolate, spicy foods, carbonated drinks, tobacco, and drugs that included acetyl salicylic acid (ASA) and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).4,10,11,13 In addition, a baseline evaluation was carried out through the ReQuest questionnaire. This instrument is validated in Spanish and enables GERD symptom improvement after PPI administration to be evaluated. It consists of 6 items for the patient to answer using a visual analog scale, and includes the domains of overall satisfaction, reflux symptoms (heartburn, regurgitation), high and low abdominal discomfort, and sleep alterations.14

The patients received treatment with 20mg of oral generic omeprazole daily, 30min before breakfast for 4 weeks, in accordance with guideline recommendations for GERD management.11,13,15 The success rate, defined as reflux symptom improvement ≥ 50%, was determined after treatment conclusion. The patients that did not respond to treatment with PPIs were considered therapeutic failures and were eliminated from the cohort and continued their conventional evaluation with their attending physician.

The patients that had a successful response were evaluated at weeks 4 and 12 after treatment suspension, resulting in a 16-week cohort follow-up period. At each evaluation, the risk factor questionnaire and the ReQuest questionnaire were applied to identify GERD symptom recurrence and establish the relapse rate, defined as a symptom increase ≥ 20% after treatment suspension.

Descriptive statistics were employed (means and standard deviations for the quantitative variables and proportions and 95% confidence intervals for the categorical variables). The Stata version 11 statistics program was used. A bivariate analysis was performed and statistical significance was set at a p<0.20. A multiple logistic regression model was carried out that was adjusted by sex, age, educational level (basic: primary and secondary school; intermediate: high school; higher: university), overweight (BMI ≥ 25-29.9kg/m2), obesity (BMI ≥ 30kg/m2), comorbidities (diabetes mellitus, high blood pressure, and gastrointestinal problems, such as dyspepsia, gastritis, hiatal hernia, irritable bowel syndrome), consumption of coffee (quartile: none, 1-3 cups per month, 4-12 cups per month, and ≥ 20 cups per month), consumption of alcohol (grams per month), citrus fruits (times per month), NSAIDs (tablets per month), chocolate (pieces per month), ASA (tablets per month), smoking (cigarettes per month), carbonated beverages (liters per month), and spicy foods (tertile: 0-4 times per month, 7-16 times per month, and ≥ 20 times per month), taking into account the baseline evaluation and the evaluation at week 12 to find possible interactions with GERD relapse 12 weeks after PPI suspension. Statistical significance was set at a p<0.05.

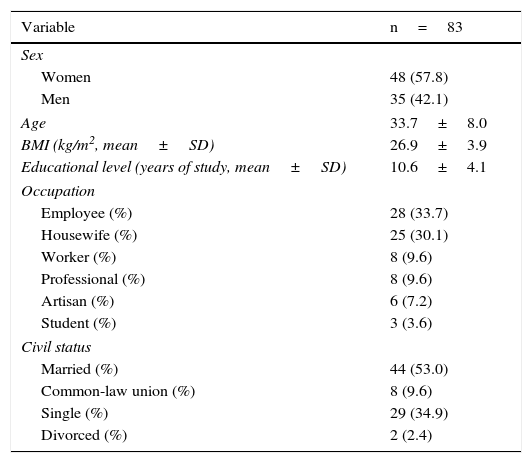

ResultsNinety patients were included, 7 (7.77%) of whom were eliminated because they were lost at follow-up. Eighty-three patients remained in the sample, 48 (57.83%) of whom were women, and the mean age of the study subjects was 33.78±3.0 years (Table 1).

General characteristics of the study patients initially evaluated.

| Variable | n=83 |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Women | 48 (57.8) |

| Men | 35 (42.1) |

| Age | 33.7±8.0 |

| BMI (kg/m2, mean±SD) | 26.9±3.9 |

| Educational level (years of study, mean±SD) | 10.6±4.1 |

| Occupation | |

| Employee (%) | 28 (33.7) |

| Housewife (%) | 25 (30.1) |

| Worker (%) | 8 (9.6) |

| Professional (%) | 8 (9.6) |

| Artisan (%) | 6 (7.2) |

| Student (%) | 3 (3.6) |

| Civil status | |

| Married (%) | 44 (53.0) |

| Common-law union (%) | 8 (9.6) |

| Single (%) | 29 (34.9) |

| Divorced (%) | 2 (2.4) |

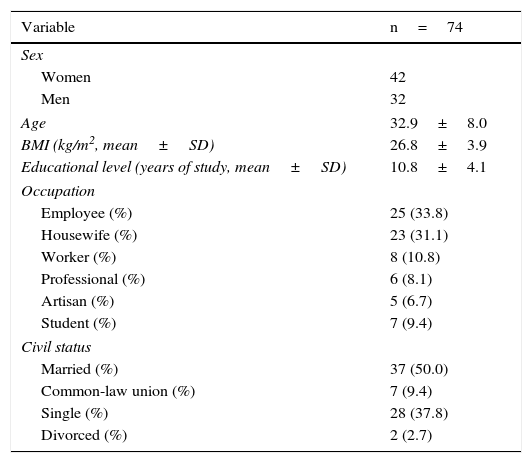

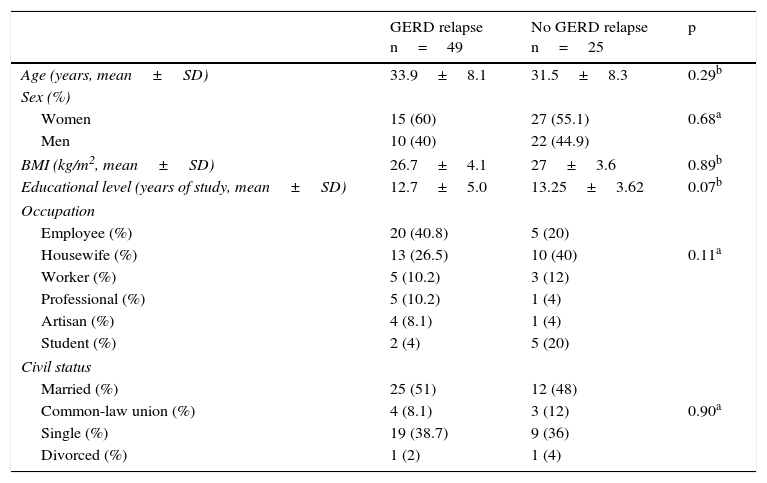

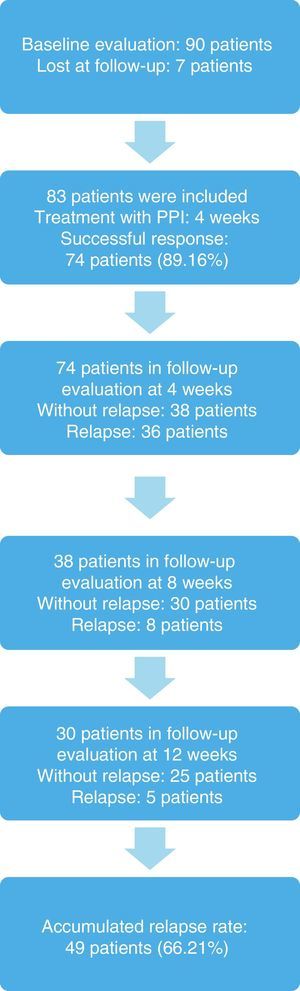

The response to treatment with omeprazole after 4 weeks was successful in 74 patients, resulting in an initial success rate of 89.16%. Of those patients, 42 (56.76%) were women, and the mean age of the patients studied was 33.24±8.18 years (Tables 2, 3, and 4). The 74 patients had a 12-week follow-up period. Symptom relapse was greater during the first 4 weeks after treatment suspension, with GERD symptoms recurring in 36 patients (48.64%); at 12 weeks, 13 more patients (17.57%) were added. The accumulated relapse rate after 12 weeks from having concluded PPI administration was 66.21% (49 patients) (fig. 1).

General characteristics of the study patients with a successful response to short-term treatment with a PPI.

| Variable | n=74 |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Women | 42 |

| Men | 32 |

| Age | 32.9±8.0 |

| BMI (kg/m2, mean±SD) | 26.8±3.9 |

| Educational level (years of study, mean±SD) | 10.8±4.1 |

| Occupation | |

| Employee (%) | 25 (33.8) |

| Housewife (%) | 23 (31.1) |

| Worker (%) | 8 (10.8) |

| Professional (%) | 6 (8.1) |

| Artisan (%) | 5 (6.7) |

| Student (%) | 7 (9.4) |

| Civil status | |

| Married (%) | 37 (50.0) |

| Common-law union (%) | 7 (9.4) |

| Single (%) | 28 (37.8) |

| Divorced (%) | 2 (2.7) |

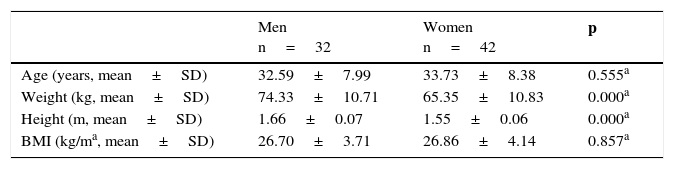

Characteristics of patients that presented with successful response to treatment with a PPI for 4 weeks.

Characteristics of the patients with successful response to short-term treatment with a PPI and later relapse at 12 weeks after treatment suspension.

| GERD relapse n=49 | No GERD relapse n=25 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years, mean±SD) | 33.9±8.1 | 31.5±8.3 | 0.29b |

| Sex (%) | |||

| Women | 15 (60) | 27 (55.1) | 0.68a |

| Men | 10 (40) | 22 (44.9) | |

| BMI (kg/m2, mean±SD) | 26.7±4.1 | 27±3.6 | 0.89b |

| Educational level (years of study, mean±SD) | 12.7±5.0 | 13.25±3.62 | 0.07b |

| Occupation | |||

| Employee (%) | 20 (40.8) | 5 (20) | |

| Housewife (%) | 13 (26.5) | 10 (40) | 0.11a |

| Worker (%) | 5 (10.2) | 3 (12) | |

| Professional (%) | 5 (10.2) | 1 (4) | |

| Artisan (%) | 4 (8.1) | 1 (4) | |

| Student (%) | 2 (4) | 5 (20) | |

| Civil status | |||

| Married (%) | 25 (51) | 12 (48) | |

| Common-law union (%) | 4 (8.1) | 3 (12) | 0.90a |

| Single (%) | 19 (38.7) | 9 (36) | |

| Divorced (%) | 1 (2) | 1 (4) | |

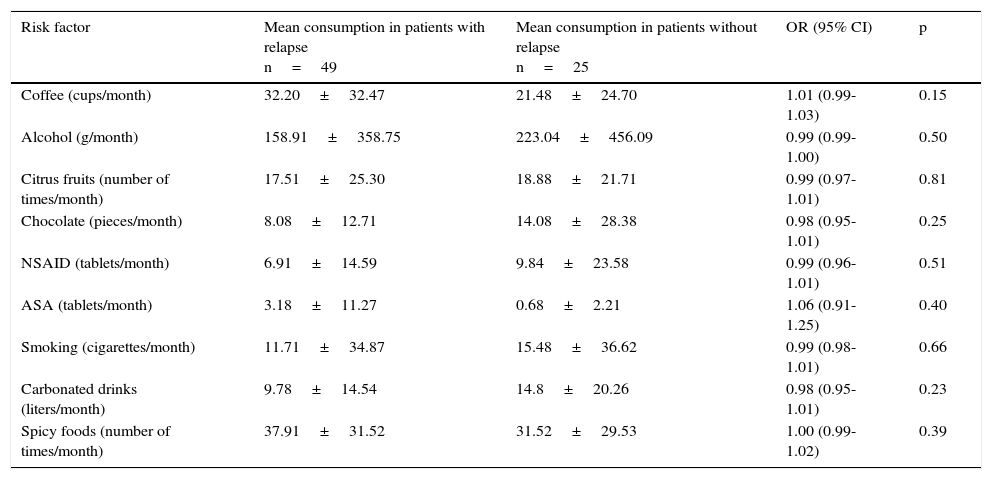

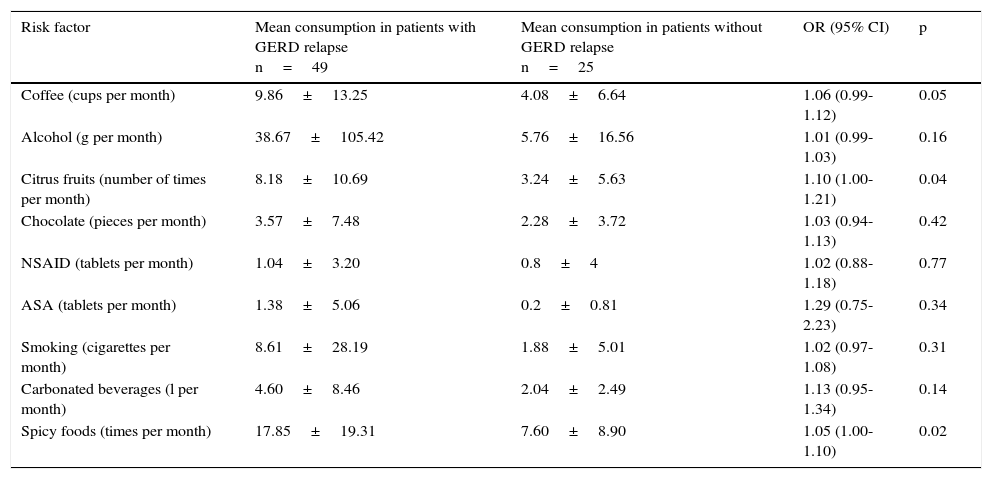

Table 5 shows the bivariate analysis of the mean consumption of the risk factors evaluated at the baseline for the patients that presented with and without relapse 12 weeks after treatment suspension. Table 6 shows the bivariate analysis of the patient evaluation 12 weeks after suspension of treatment with the PPI. The multiple logistic regression model showed that having a basic educational level (primary school, secondary school), or lower, increased the possibility of GERD relapse 24.95-fold, consumption of citrus fruits ≥ 12 times per month increased the possibility of relapse 14.76-fold, and the consumption of NSAIDs ≥ 1 tablet per month increased the possibility of GERD relapse 27.77-fold at 12 weeks after suspension of treatment with the PPI (Table 7).

Bivariate analysis of the mean consumption in the baseline evaluation in patients with and without GERD relapse at 12 weeks after treatment suspension.

| Risk factor | Mean consumption in patients with relapse n=49 | Mean consumption in patients without relapse n=25 | OR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coffee (cups/month) | 32.20±32.47 | 21.48±24.70 | 1.01 (0.99- 1.03) | 0.15 |

| Alcohol (g/month) | 158.91±358.75 | 223.04±456.09 | 0.99 (0.99- 1.00) | 0.50 |

| Citrus fruits (number of times/month) | 17.51±25.30 | 18.88±21.71 | 0.99 (0.97-1.01) | 0.81 |

| Chocolate (pieces/month) | 8.08±12.71 | 14.08±28.38 | 0.98 (0.95- 1.01) | 0.25 |

| NSAID (tablets/month) | 6.91±14.59 | 9.84±23.58 | 0.99 (0.96-1.01) | 0.51 |

| ASA (tablets/month) | 3.18±11.27 | 0.68±2.21 | 1.06 (0.91- 1.25) | 0.40 |

| Smoking (cigarettes/month) | 11.71±34.87 | 15.48±36.62 | 0.99 (0.98-1.01) | 0.66 |

| Carbonated drinks (liters/month) | 9.78±14.54 | 14.8±20.26 | 0.98 (0.95-1.01) | 0.23 |

| Spicy foods (number of times/month) | 37.91±31.52 | 31.52±29.53 | 1.00 (0.99-1.02) | 0.39 |

Bivariate analysis of the mean consumption in the evaluation at 12 weeks after treatment suspension in patients with and without GERD relapse.

| Risk factor | Mean consumption in patients with GERD relapse n=49 | Mean consumption in patients without GERD relapse n=25 | OR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coffee (cups per month) | 9.86±13.25 | 4.08±6.64 | 1.06 (0.99-1.12) | 0.05 |

| Alcohol (g per month) | 38.67±105.42 | 5.76±16.56 | 1.01 (0.99-1.03) | 0.16 |

| Citrus fruits (number of times per month) | 8.18±10.69 | 3.24±5.63 | 1.10 (1.00-1.21) | 0.04 |

| Chocolate (pieces per month) | 3.57±7.48 | 2.28±3.72 | 1.03 (0.94-1.13) | 0.42 |

| NSAID (tablets per month) | 1.04±3.20 | 0.8±4 | 1.02 (0.88-1.18) | 0.77 |

| ASA (tablets per month) | 1.38±5.06 | 0.2±0.81 | 1.29 (0.75-2.23) | 0.34 |

| Smoking (cigarettes per month) | 8.61±28.19 | 1.88±5.01 | 1.02 (0.97-1.08) | 0.31 |

| Carbonated beverages (l per month) | 4.60±8.46 | 2.04±2.49 | 1.13 (0.95-1.34) | 0.14 |

| Spicy foods (times per month) | 17.85±19.31 | 7.60±8.90 | 1.05 (1.00-1.10) | 0.02 |

Multivariate analysis. Risk factors for GERD relapse at 12 weeks after treatment suspension.

| OR (95% CI) | Standard error | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 1.02 (0.20-5.20) | 0.85 | 0.97 |

| Age (years) | 0.99 (0.89-1.11) | 0.05 | 0.97 |

| Educational level (basic) | 24.95 (1.92-323.79) | 32.63 | 0.01 |

| Educational level (intermediate) | 1.84 (0.24-4.09) | 1.91 | 0.55 |

| Comorbidity | 0.34 (0.06-1.83) | 0.29 | 0.21 |

| Overweight (BMI ≥ 25-29.9 kg/m2) | 1.76 (0.22-13.64) | 1.83 | 0.58 |

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) | 0.25 (0.01-3.46) | 0.34 | 0.30 |

| Coffee consumption | |||

| Quartile 3 (4-12 cups per month) | 1.00 (0.12-7.84) | 1.05 | 0.99 |

| Quartile 4 (> 20 cups per month) | 12.02 (0.51-278.12) | 19.26 | 0.12 |

| Alcohol consumption | 1.05 (0.15-7.29) | 1.04 | 0.95 |

| Citrus fruit consumption (≥ 12 times per month) | 14.76 (1.90-114.57) | 15.43 | 0.01 |

| NSAID consumption (≥ 1 tablet per month) | 27.77 (1.12-686.11) | 45.44 | 0.04 |

| Chocolate consumption | 0.86 (0.18-4.06) | 0.68 | 0.85 |

| ASA consumption | 1.63 (0.12-21.63) | 2.15 | 0.70 |

| Smoking | 0.51 (0.06-3.88) | 0.53 | 0.51 |

| Carbonated beverage consumption | 4.24 (0.32-55.05) | 5.55 | 0.26 |

| Spicy food consumption | |||

| Tertile 2 (7-16 times per month) | 1.39 (0.17-11.17) | 1.48 | 0.75 |

| Tertile 3 (≥ 20 times per month) | 4.06 (0.47-34.59) | 4.44 | 0.19 |

In this 16-week cohort study, the success rate for the initial treatment with omeprazole was 89.2%, similar to that described in other studies that used PPIs for treating GERD patients.2,3 The accumulated relapse rate at 12 weeks after treatment suspension was high (66%), especially during the first month after treatment suspension (48.6%). Higher GERD relapse rates have been described during the first month after treatment completion, which could explain our results at 4 weeks.2

Despite the fact that some studies have reported a lower relapse rate than ours (11-44%), we found no analyses comparable to our study conducted on primary care patients for identifying risk factors associated with GERD relapse, in which patients with no alarm symptoms received short-term treatment with omeprazole. The majority of studies reporting a GERD relapse rate have been carried out on tertiary care patients, some of whom are classified as having esophagitis and who receive maintenance treatment for that entity, which could explain the differences found.2,5,16–18

In addition, given that it is a pathology that tends to become chronic, a longer treatment period of approximately 8-12 weeks could reduce the relapse rate of GERD and improve the quality of life of the affected individuals.11,13,18 The systematic review carried out by Sigterman et al. showed that PPIs are more effective than H2-antagonists and prokinetics in treating GERD.19 A satisfactory response rate to PPIs (> 90%) has been reported in patients with characteristic GERD symptoms and esophageal erosions at 8 weeks in the majority of cases and even in the short term (4 weeks). However, in patients with persistent or recurrent symptoms, response is related to their predominant symptom. In patients with persistent GERD symptoms, longer treatment with PPIs would offer better results and additional studies would be indicated.11,13,19–21 The findings of the systematic review reported by Donnellan et al. support the idea that a long period of treatment of esophagitis prevents relapse, in relation to both symptoms of GERD and endoscopic alterations.18

There is evidence that some lifestyle factors, such as overweight, obesity, smoking, alcohol consumption, postprandial dorsal decubitus position, and the consumption of certain foods and drugs are associated with GERD symptoms. However, there is little evidence to support the efficacy of lifestyle modifications for reducing GERD symptoms.4,6–11,13,22 Ours is the first study to identify risk factors associated with GERD relapse conducted on primary care patients successfully treated with a PPI.5,7

The bivariate analysis, taking the baseline evaluation of the patients into consideration, showed that coffee consumption increased the possibility of GERD relapse 12 weeks after the suspension of treatment with a PPI. The bivariate analysis with the data from the final evaluation (12 weeks after treatment suspension) showed that the consumption of coffee, alcohol, citrus fruits, carbonated beverages, and spicy foods increased the risk for GERD relapse.

The multivariate analysis took into account the risk factors obtained in the baseline evaluation before the patients received GERD treatment, to avoid bias due to that treatment. It also considered the evaluation of the risk factors at 12 weeks from treatment suspension, given that this was the final evaluation for determining the presence of relapse after suspending the treatment with a PPI. The logistic regression analysis found that the basic (primary and secondary) level of education, or lower, the consumption of citrus fruits ≥ 12 times per month, and the consumption of an NSAID ≥ 1 tablet per month increased the possibility of GERD relapse at 12 weeks after suspension of successful treatment with a PPI. These findings coincide with those described in other studies.4,7,8

There is still controversy as to the consumption of ASA and NSAIDs. Some studies report that ASA and NSAID consumption was a protective factor for GERD symptoms and the progression of Barrett's esophagus,23,24 but those drugs are also reported to be associated with GERD by damaging the esophageal mucosa.8,25 Therefore, more data are required to help confirm these results.

The behavior of overweight, obesity, smoking, or the consumption of coffee, carbonated beverages, chocolate, spicy foods, or ASA as risk factors for GERD relapse at 12 weeks after the suspension of PPI administration was not corroborated in our study, unlike other studies that have shown their association with GERD.4,9–11,21,25 This difference is most likely due to the smaller sample size of our study.

One of the limitations of our study's methodology was the application of ad hoc questionnaires, which could have introduced variations in the responses related to the perception of the individuals surveyed and possible bias in regard to memory and lifestyle modifications upon presenting with symptoms or noticing symptom improvement with the treatment. The questionnaire applied was based on the results of previous studies showing that certain factors were associated with GERD and GERD relapse. No validated risk factor questionnaire is available in the literature, but the patients were interviewed based on the information of previous studies that have shown a certain association of these factors with GERD. The ReQuest questionnaire, validated in Spanish, was also utilized to study the later symptoms in the patients and to determine the GERD relapse rate.

It should be mentioned that it was not possible to obtain more concrete data on the consumption characteristics of certain risk factors for GERD relapse, such as coffee, alcohol, citrus fruits, and spicy foods. To avoid bias upon selecting a certain quantity as the cutoff point, questions were on amounts consumed, and the answers were analyzed using the Stata 11.1 statistics program. A bivariate statistical analysis was carried out and the variables with statistically significant results were then included in the multivariate analysis. Tertiles and quartiles were then formed according to the data distribution, or as present or absent risk factors according to the results produced with the statistics program. Only the consumption of citrus fruits and NSAIDs increased the possibility of GERD relapse. There were no significant differences in the other variables. Another study limitation was the fact that no statistical analysis was done with respect to the changes in weight of the patients during the evaluations. However, the multivariate analysis evaluated the interaction of BMI with GERD relapse.

The study patients had adequate treatment adherence with the daily dose of 20mg of omeprazole that has shown satisfactory results in GERD management.11,13,15 Thus, a lack of treatment adherence cannot be an explanation for GERD relapse after short-term treatment with omeprazole in our cohort. Treatment adherence was documented through the patient interview, given that neither the healthcare personnel nor the authors directly administered the medication because of the cohort study design.

Despite the important limitations due to the type of analysis and methodology, our study is strengthened by certain characteristics. A 16-week follow-up period was carried out on the patients that had a successful response to the short-term treatment with a PPI, with a baseline evaluation at the beginning of the treatment, and then 4, 8, and 12 weeks after suspension of treatment with the PPI.

The importance of conducting this study lies in the fact that the majority of the population receives primary care attention, given that it is the first patient/physician contact, and therefore there is a greater impact on health. In addition, the study patients were incident cases of GERD identified through the medical history and the CDQ. It should be mentioned that these patients had received no type of treatment for GERD, which enabled a more reliable evaluation of the treatment response, determination of the relapse rate, and identification of possible risk factors. There was a high GERD relapse rate in the study patients and a significant association with certain risk factors in the multivariate analysis, suggesting that a change in lifestyle could reduce GERD symptoms.

A systematic review of 16 randomized clinical trials evaluated the impact of lifestyle on patients with GERD and concluded that only weight loss and head elevation when sleeping improved pH study findings and GERD symptoms.20 In a recent systematic review conducted by Kang and Kang, they reported that there were controversial results in relation to the association between smoking, alcohol, and dietary factors and the development of GERD, most likely due to methodological problems of the studies. Lifestyle measures, such as weight loss, quitting smoking, and time and number of meals, can be beneficial for reducing GERD symptoms. However, evidence is limited with respect to the consumption of alcohol, carbonated beverages, coffee, fats, spicy food, chocolate, and peppermint.26

Lifestyle changes are often recommended, but very few patients carry them out. There are many reasons for this resistance, given that it involves social, cultural, and individual factors. It is important to promote healthy lifestyles in the population at all levels of healthcare, especially in primary care, since it is the level of care received by the majority of the population.

In conclusion, the GERD relapse rate in primary care patients that received short-term treatment with a PPI for 4 weeks was high. The consumption of citrus fruits ≥ twelve times a month and a NSAID ≥ 1 tablet a month increased the possibility of GERD relapse. Our study results suggest that in addition to longer drug treatment duration, changes in lifestyle are an important part of management in these patients for reducing the relapse rates after successful treatment with a PPI.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the relevant clinical research ethics committee and with those of the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

FundingThis study was conducted with funds received from the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social and was supported by Nycomed México, which gave permission to use the ReQuest questionnaire.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: López-Colombo A, Pacio-Quiterio MS, Jesús-Mejenes LY, Rodríguez-Aguilar JEG, López-Guevara M, Montiel-Jarquín AJ, et al. Factores de riesgo asociados a recaída de enfermedad por reflujo gastroesofágico en pacientes de primer nivel de atención exitosamente tratados con inhibidor de la bomba de protones. Revista de Gastroenterología de México. 2017;82:106–114.

See related content at DOI: 10.1016/j.rgmxen.2017.03.004, Vázquez-Elizondo G. Gastroesophageal reflux disease: Dichotomy of the clinical trial and clinical practice. Revista de Gastroenterología de México.2017;82:103–105.