Primary gastric lymphoma (PGL) is an uncommon tumor that accounts for 4 to 20% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas and 5% of primary gastric neoplasias.1 At present, surgery is only recommended as urgent treatment for patients that present with perforation or severe bleeding, or as palliative treatment.2–5 Spontaneous gastric perforation in the absence of chemotherapy is extremely rare.4 We present herein a case of gastric diffuse large B-cell lymphoma that required surgical treatment because it had the two characteristics that make surgical intervention essential: perforation and gastric outlet obstruction.

A 36-year-old man, whose father died of gastric cancer at 31 years of age, had no other remarkable personal pathologic history. His current illness began one month before hospital admission with progressive intolerance to food, nausea, vomiting of the stomach content, and occasional colicky pain in the epigastrium. Endoscopy revealed chronic erosive gastropathy, a lesion infiltrating the antrum, and stricture of the pylorus due to a lesion. Biopsies were taken.

Seven days prior to his admission he presented with non-radiating colicky pain in the epigastrium of 10/10 intensity that did not exacerbate or attenuate, leading to his hospitalization. Laboratory tests reported severe anemia and leukocytosis. As part of his evaluation protocol, abdominal tomography was performed, which identified the presence of gastric antrum wall thickening of up to 20mm, adenopathies at the level of the duodenal bulb, and inflammatory adhesions in the gastric antrum situated toward the liver and gallbladder.

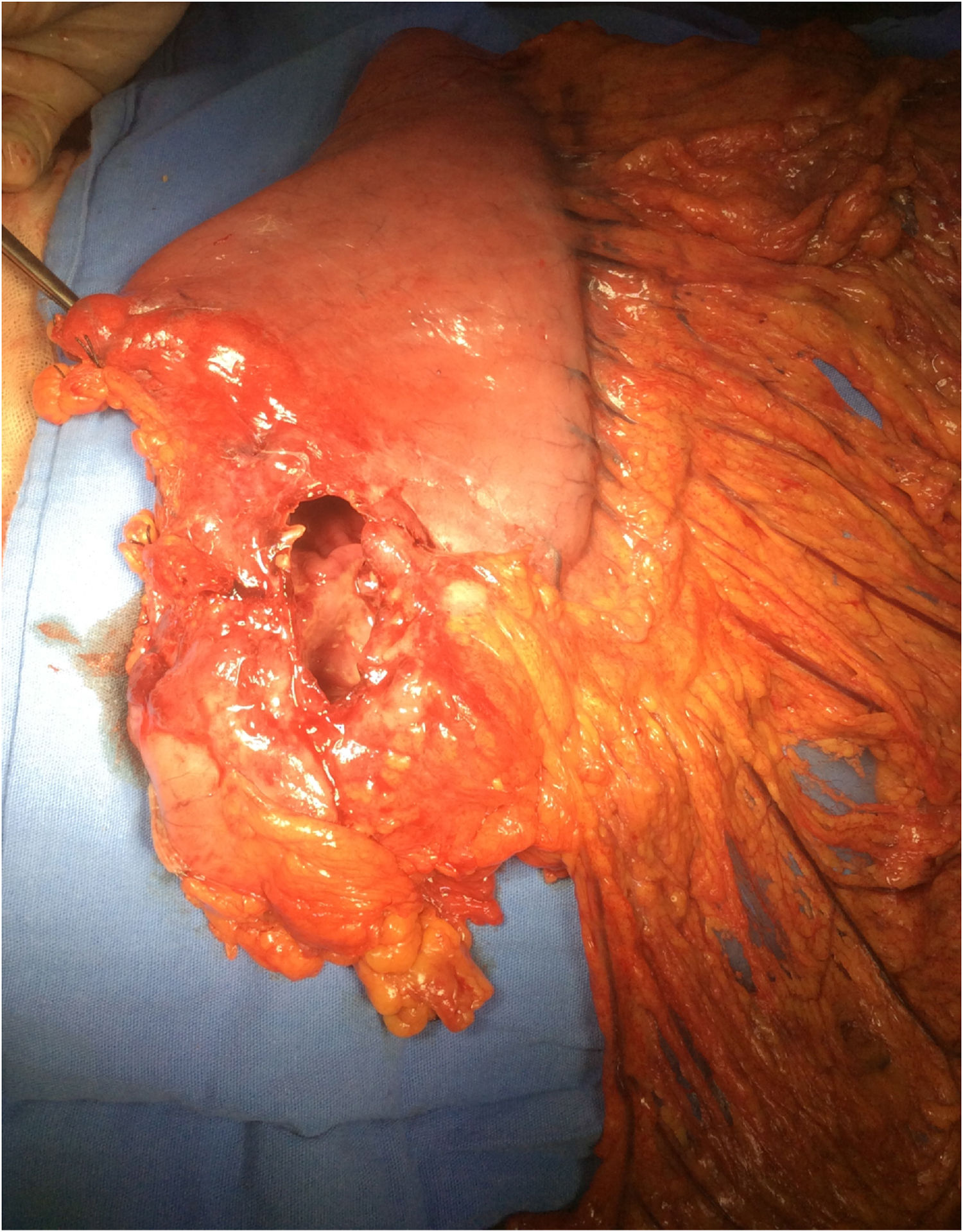

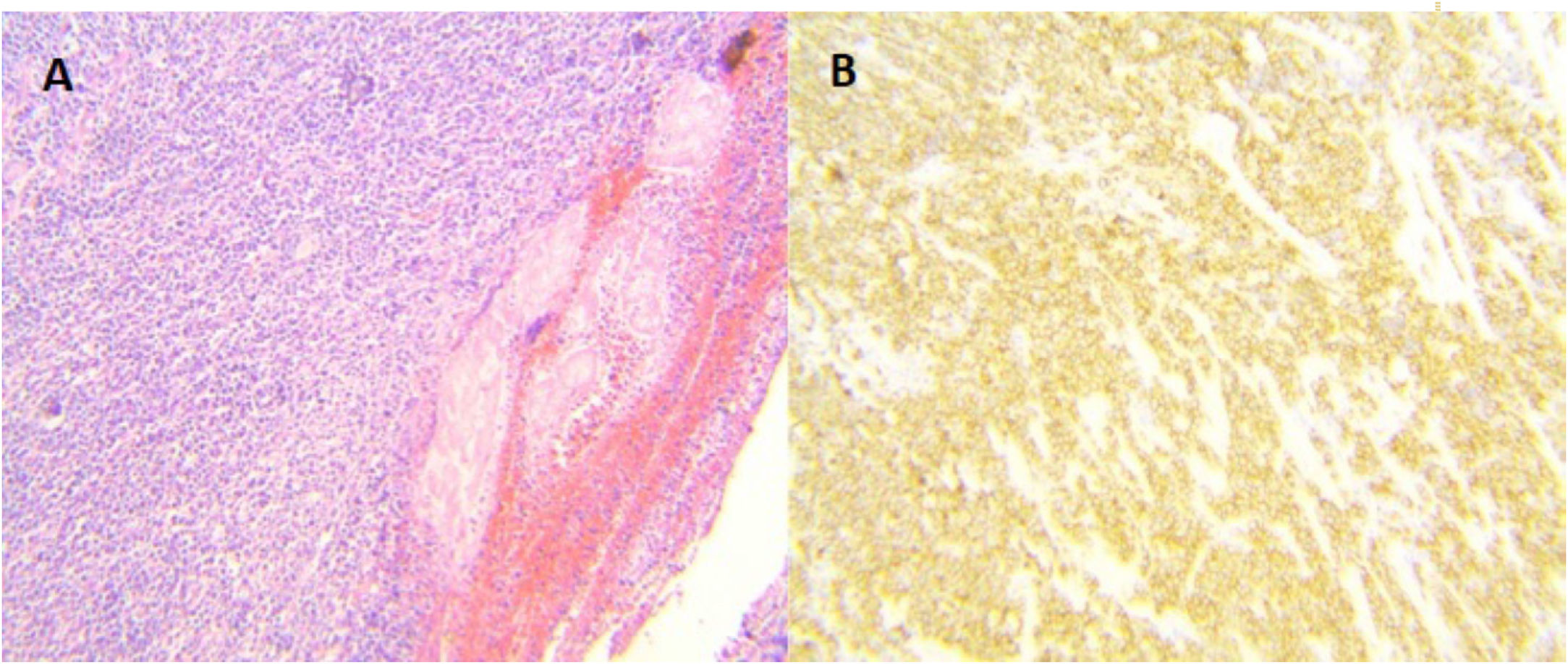

Surgery was programmed, and it revealed thickening of the gastric wall, which was ulcerated, perforated, and sealed in the direction of the liver and gallbladder (fig. 1). Subtotal gastrectomy and cholecystectomy were carried out and liver biopsy was taken at the site of probable tumor invasion due to contiguity in segment V. The histopathologic study of the intraoperative and definitive sample reported ulcerated and perforated gastric diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (fig. 2A-B). The patient had satisfactory postoperative progression and was released to continue outpatient follow-up and treatment.

The most common site for extranodal primary non-Hodgkin lymphoma is the stomach. It presents as low-grade mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) in 40% of the cases and as high-grade diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) in 60%.1,6 Primary gastric lymphoma frequently presents with nonspecific symptoms and diagnosis is often delayed. Nonspecific abdominal pain (50%) and dyspepsia (30%) are the most common presentations. B symptoms (fever, night sweats, and weight loss) are infrequent, in contrast to nodal lymphomas, causing diagnostic delay.7 Imaging studies can reveal wall thickening, but in general it is difficult to distinguish gastric lymphoma from other types of gastrointestinal cancer through that medium. Endoscopy and biopsy are more reliable methods for confirming diagnosis.8

Today, primary gastric lymphoma treatment has moved away from surgery, in favor of chemotherapy regimens. Surgery is no longer the cornerstone of treatment and is limited to cases of perforation, bleeding, and tumor-related obstruction.1,3,4

In that context, patients with primary gastric diffuse large B-cell lymphoma related to Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) that have favorable characteristics are eligible for bacterial eradication therapy as exclusive treatment, maintaining conventional chemoimmunotherapy for non-responder patients.3 Treatment varies according to the histology of the malignant lymphoma. Tumor cells are known to be positive for CD20. Rituximab is an anti-CD20 antibody and is highly effective in nodal DLBCL.1 CHOP with or without rituximab is first-line chemotherapy for DLBCL.9

The cause of perforation in gastric lymphoma is different in cases that receive chemotherapy and those that do not. Perforation in patients that receive chemotherapy is due to the weakening of the gastric tissue, associated with rapid tumor necrosis and tumor lysis due to chemotherapy. On the other hand, there are 2 different patterns of spontaneous perforation. First, spontaneous perforation results from an ulcer and tumor necrosis that has reached the subserosa. Second, perforation is the result of an ulcer that has thin conjunctive tissue and the absence of tumor.10

In short, the best treatment should be chosen according to tumor location, clinical stage, pathologic pattern, and the presence or absence of complications. Overall 5-year survival reported for multimodal therapy is between 50 and 70%.1,7

The frequency of clinical presentation of gastric lymphoma complicated by obstruction and perforation is extremely low, and even though surgery is no longer the cornerstone of treatment for that pathology, gastrectomy with reconstruction, in addition to medical adjuvant therapy, is indicated when those complications present.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Financial disclosureNo financial support was received in relation to this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Ceniceros-Cabrales AP, Sánchez-Fernández P. Linfoma difuso de células grandes B gástrico perforado: reporte de un caso y revisión de la literatura. Revista de Gastroenterología de México. 2019;84:412–414.